- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It used to be said in decades gone by that overseas acting luminaries only came to Australia when their stars were in decline. This was never true in the case of Sybil Thorndike, who was critically acclaimed here, and widely admired as a person. She was not one of those who was past her prime – or, like some, never had one. She remained in her prime until she died in 1976. It is indeed hard to imagine her contemplating any other approach.

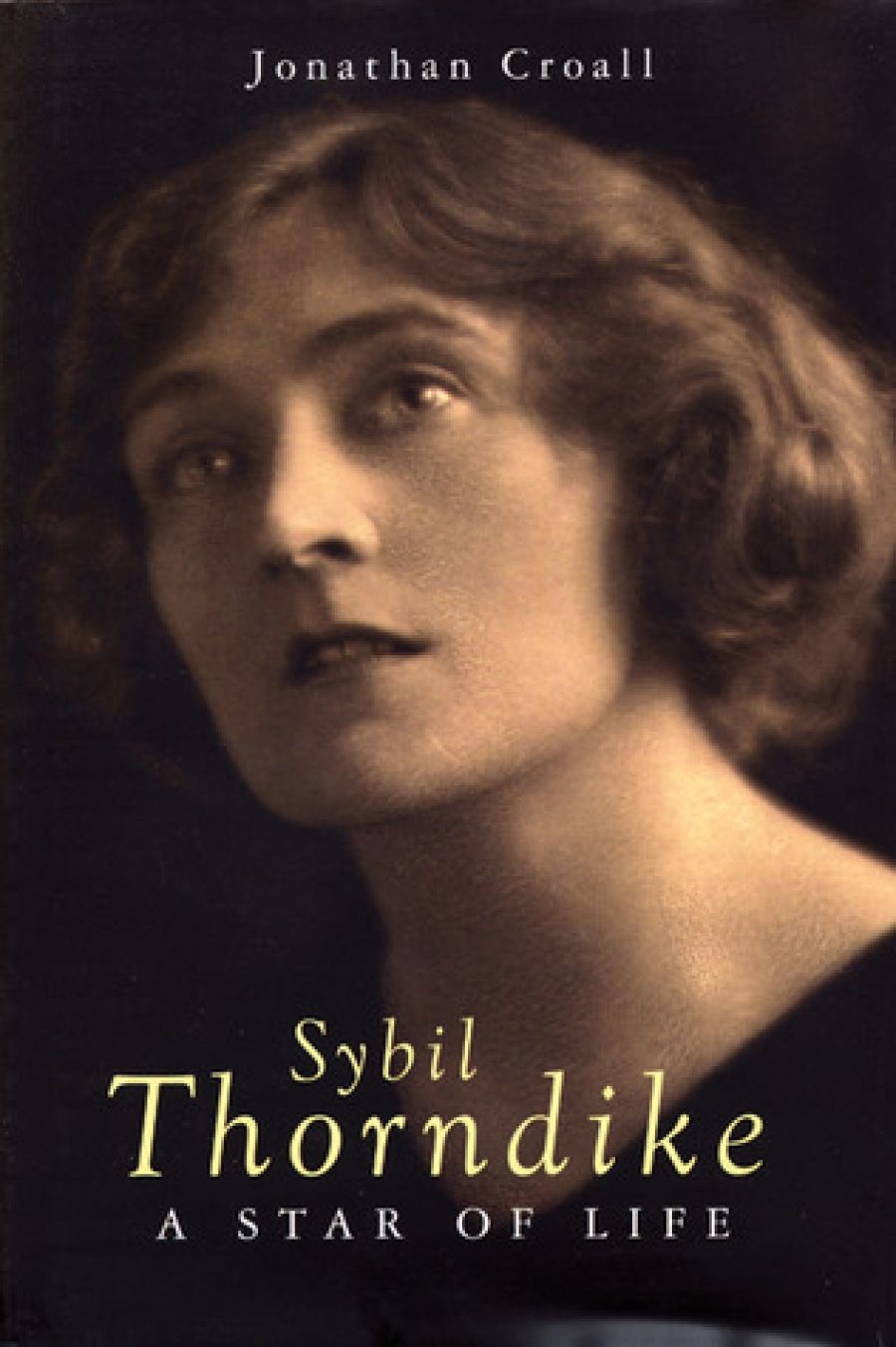

- Book 1 Title: Sybil Thorndike

- Book 1 Subtitle: A star of life

- Book 1 Biblio: Haus Books, £25 hb, 584 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Z2DzR

Jonathan Croall’s magisterial biography (the equal of his Gielgud, 2001) not only persuades us of her individual pre-eminence but conveys a sense of a career’s encapsulating a history of much twentieth-century British theatre. And not just in Britain but also in such far-flung outposts as the Middle East, South Africa and Australia (and we were pretty far-flung when she first came here in 1932), as well as touring Greek tragedy and Shakespeare to mining towns unused to such recherché entertainments. (She believed it an actor’s duty to tour, disapproving of Edith Evans’s distaste for it.) A whole chronicle of changes in British theatre emerges: from the tail-end of Victorian melodrama, Granville-Barker’s withdrawal from the scene, the way serious actors would happily work in variety, the incidence of fringe stage societies, to the Royal Court’s angry new plays in the late fifties, and so on.

If she gave some memorable accounts of such great classic roles, notably with the Old Vic, she also regularly and enthusiastically embraced the new. She took on T.S. Eliot’s The Family Reunion in 1956, Graham Greene’s The Potting Shed in 1957, Enid Bagnold’s The Chalk Garden in 1957–58 (hurtling round Australian stages, at seventy-five, in this) and Marguerite Duras’s The Viaduct in 1967. Of the latter, she wrote with characteristic relish, ‘I’ve not loved a play so much since the Greeks and Saint Joan’, and Croall makes us feel the adventurous courage of a woman in her eighties taking on this particular challenge.

As well as in The Chalk Garden, Australians had the chance to see her Medea and Saint Joan in the 1930s; in 1954 she and her husband of sixty years, Lewis Casson, gave sell-out poetry recitals here; and in the following year she played the domineering Mrs Railton-Bell in Terence Rattigan’s Separate Tables and the Grand Duchess in his feeble The Sleeping Prince, at which audiences fell gratefully on her appearances. She reprised this latter role in the film version, The Prince and the Showgirl, starring Laurence Olivier and Marilyn Monroe. Notoriously unpunctual and forgetful, Monroe incurred Olivier’s (probably justified) wrath, but Thorndike ‘invariably took Marilyn’s side’, publicly berating Olivier: ‘Don’t you realise what a strain the poor girl is under? She hasn’t had your years of experience. She is far from home in a strange country, trying to act in a strange part.’ It is worth quoting this as an illustration of the largeness and generosity of spirit that informed her working life.

Speaking of films, she appeared in about three dozen, dating back to the silent days, but most notably perhaps from the mid-1930s, when she played Lady Jane Grey’s nurse in Tudor Rose. She was an imposing ‘General’ in Gabriel Pascal’s Major Barbara (1941), a brace of terrible old harridans in Nicholas Nickleby (1947, as Mrs Squeers) and Britannia Mews (1948, her character succinctly called The Sow), and appeared for two famously unpleasant directors: Alfred Hitchcock in Stage Fright (1950) and Michael Powell in Gone to Earth (1950), neither of whom was likely to daunt her as they had many actors of lesser mettle. She brought her formidable presence to bear on very dignified cameos in two biopics: The Lady with the Lamp (1951) and Melba (1953). In Lewis Milestone’s conventional account of the great soprano, she is a humane and imposing Queen Victoria who reassures Melba that she knows about the conflicts between love and other demands.

Sybil (if it seems impertinent to refer to her as ‘Sybil’, I can only say that it seems too remote to call her ‘Thorndike’) certainly knew about such conflicts but took them in her stride, as she did everything in her life. What makes Croall’s study a great biography as distinct from a list of stage performances, most of which his readers will never have seen, are two key elements. First, he has, no doubt as a result of the most scrupulous research, managed to bring those performances to life in a way that is not always common in theatrical biography. This has involved his piecing together contemporary accounts and recollections of those present, so that one ‘sees’ her Joan or her Miss Moffat in The Corn Is Green. Of the latter, he writes that author Emlyn Williams’s ‘description of Miss Moffat might also have been that of Sybil: she was “a healthy Englishwoman with an honest face, clear beautiful eyes, and unbounded vitality … Her most prominent characteristic is her complete unsentimentality.” Not surprisingly, Sybil seemed to mesh with the part straight away.’ There is much more about this role and innumerable others that one could adduce, but it is the second element I want to stress here.

By this I mean that ‘actress’ is only one element that made her ‘A Star of Life’. What Croall has done is to pay equal due to the political activist, the outspoken feminist, the practising Christian, the extraordinary wife and mother, all roles entered into with huge vitality and openness to experience. He makes us aware how her pacifism and concern for the situation of women informed her performances in, say, The Trojan Women and Medea; how, over her whole acting trajectory, her own views and principles fed into her work.

She emerges as a sort of unstoppable force, utterly without self-consciousness or vanity. Christopher Isherwood ‘found her even more wonderful than [he] expected. She is a sort of a saint – if only because, as an actress, she still doesn’t seem to give a damn about what sort of impression she creates.’ Goodness, though it may sound cynical to say so, isn’t normally the most compelling of literary subjects; somehow, Croall, perhaps infected with Sybil’s own unflagging zest, pulls off the feat of never rendering it dull. He doesn’t ignore her faults: she had a formidable temper when roused (she gave Olivier ‘hell’ when he left his first wife, and ‘hit him in the face’ when he made a discouraging speech to his Chichester cast for Uncle Vanya); she was a loving but somewhat haphazard mother (one daughter said she was glad to get into school uniform to counteract Sybil’s insistence on how ‘different’ her children were); and she and Lewis Casson, on stage one of the great co-starring teams of the century, had their share of spats.

But nothing can – and no one seems to want to – detract from the exhilarating air she radiates of sheer goodness in the most stimulating action. She was the first person I ever interviewed: I was a callow twenty-year-old and she made me feel as if she had been waiting all her life to meet me. This superb biography reminds me of how I felt all those years ago – and how many other people must have felt the same.

Comments powered by CComment