- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letter collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

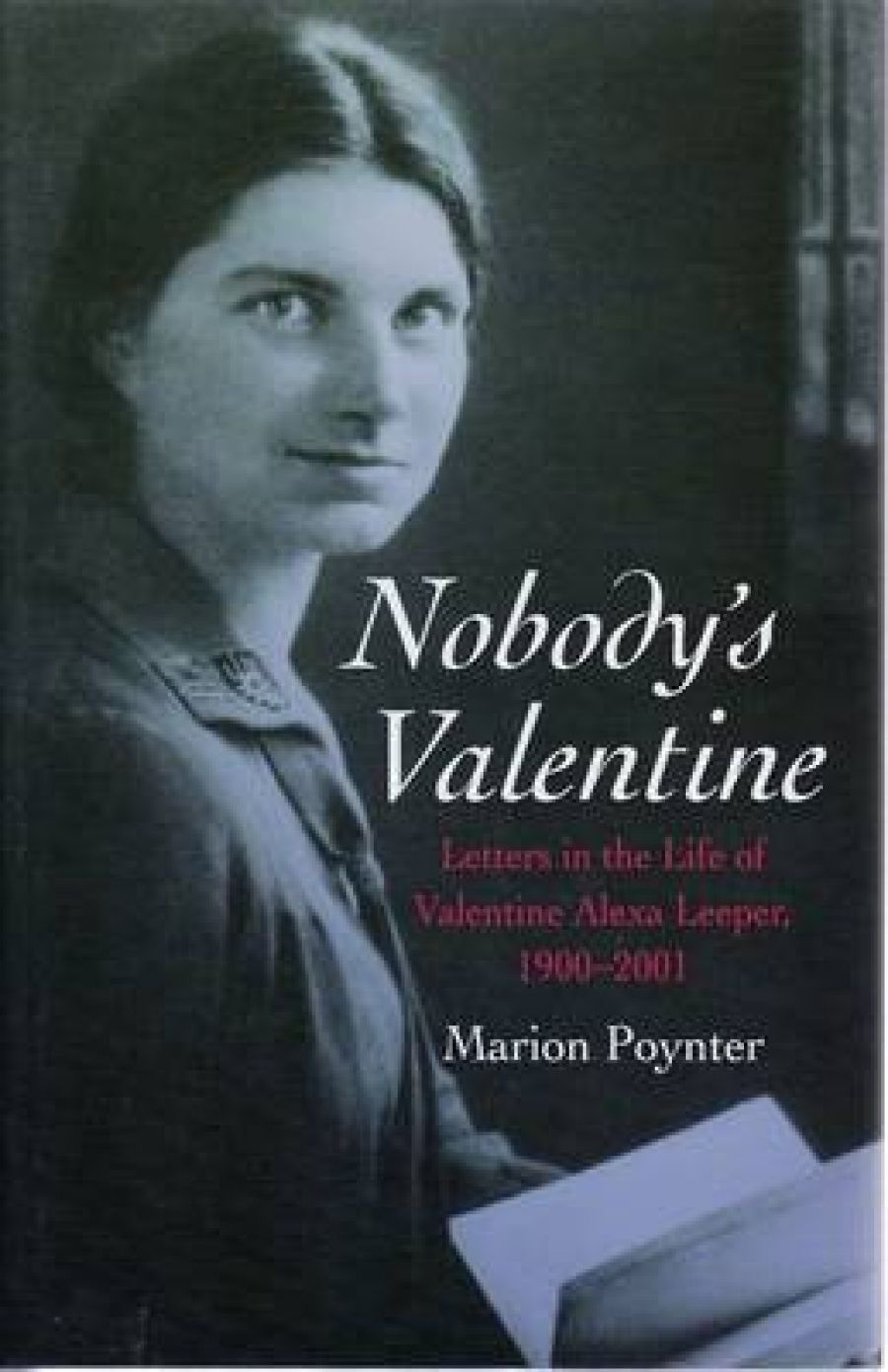

Valentine Alexa Leeper: it’s a name to conjure with. The daughter of the first warden of the University of Melbourne’s Trinity College, Alexander Leeper, she was christened ‘Valentine’ because she was born on 14 February. No name could have been less appropriate: she was to prove a committed spinster. She was remarkable for a number of reasons, not least of which was that her life spanned an entire century. Born in 1900, she survived into the twenty-first century. Although her life experience might have appeared narrow and confined (she never travelled abroad, for example) Valentine had the advantage of growing up in a university environment and was possessed of a formidable intellect; her interests were wide and she was active in many organisations, ranging from the League of Nations Union to the Victorian Aboriginal Group.

- Book 1 Title: Nobody’s Valentine

- Book 1 Subtitle: Letters in the life of Valentine Alexa Leeper 1900–2001

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah, $59.99 hb, 464 pp

Above all, she was an inveterate, sometimes incorrigible, letter-writer: to relatives, friends, churchmen, politicians, newspapers and, indeed, any organisation or person with whom she had a bone to pick. By nature outspoken and argumentative, and unafraid of being laughed at as an eccentric, Valentine Leeper had the dubious privilege of coming to be regarded as a ‘character’. Marion Poynter has mined the treasure trove of Valentine’s correspondence and woven her letters into a narrative which is, in effect, a biography. Given that Valentine could be seen as living her life through her letters, this treatment is more than justified.

From the beginning, Valentine seemed determined to see herself as an ugly duckling. Her father assisted her in this self-identification, remarking in his diary on the day of her birth, ‘[I] fear very ugly nose – like mine – will be no beauty’. At the age of eleven, she hated being a bridesmaid at her half-sister Kitty’s wedding and noted in her diary, with some satisfaction, one suspects, ‘I looked very ugly’. According to her father, she was ‘distressingly shy’, and there was barely a whiff of romance in her life. Indeed, he described his daughter as shrinking from ‘young men’s company as from a wild beast’. Dances were an ordeal, and it was perhaps morally convenient that she came to disapprove of dancing. Attending a Student Christian Movement conference at Woodend, she dreaded the party games. ‘My lack of humour, my sense of disgust, my hatred of rag-time, noise & foolery’ combined to put her to flight. And yet she responded enthusiastically to the serious agenda of the conference, and it is surprising to find her in colloquial form, praising a speaker’s ‘bonza address’.

It was perhaps symptomatic of her early diffidence and uncertainty that she first enrolled in Science at Melbourne University before realising that her interests lay elsewhere and switching to Arts. By this time, Alexander Leeper had retired from Trinity, and when Valentine graduated she in effect became his unpaid secretary. Increasingly, she and her younger sister, Molly (who, although more sociably inclined than Valentine, also did not marry), committed themselves to caring for their parents.

Alexander was a martyr to hypochondria, and their mother Mary (always known in the family as Madre) had failing eyesight. Valentine embraced this fate with passionate devotion. She never regarded it as a burden: indeed, it seemed to give her life moral purpose.

At the same time, she was throwing off the diffidence of youth and beginning to project the formidable manner which would become her hallmark. Short in stature, she had a loud voice which she was not afraid to use; she could appear grimly humourless, although this was not the image she presented to relatives and women friends. Her own father spoke of her ‘dreadfully bad manners’, while full of praise (as well he might have been) for her ‘wonderful goodness’. Her clothes were deliberately dowdy; she knitted her own brown cardigans, year in, year out. Indeed, when one year she was unable to procure the exact, unattractive shade of dark brown wool to which she had sentenced herself for life, she took the Wool Bureau and wool manufacturers to task in a volley of letters.

Valentine was the eldest child of Alexander’s second marriage, but she had grown up with the two daughters and two sons of his first marriage to Adeline, who had died in 1893. Her two half-brothers, Allen and Rex, went off to Oxford when she was still a child and, pursuing successful careers in the British Foreign Office, were, except for a brief working visit by Allen, never to return. Valentine was particularly fond of Allen and was in regular contact with him; he served as her window onto the world, providing her with up-to-date, authoritative assessments of the European situation which she was able to draw upon in her work for the League of Nations Union. On his death, Allen was described by his friend Harold Nicolson as ‘a man who made virtue seem inevitable’.

Valentine had a Christian concern for the problems facing minorities. When the plight of Aborigines began to attract attention in the period between the wars, Valentine and a SCM friend, Amy Brown, founded an Aboriginal Studies Group in 1929, which subsequently became the Victorian Aboriginal Group, dedicated to activating a ‘public conscience’ on the issue. She was a founding member of the Anthropological Society of Victoria (1934). But, perhaps inevitably, the future she envisaged for Aborigines was assimilationist.

More surprising was a brief experience as a media identity. As early as 1940 she had had some exposure on radio in general knowledge quizzes. But in 1950 she joined the panel, along with a young Barry Jones, of a popular Saturday night program, ‘Information Please’. As Marion Poynter remarks, Valentine ‘had a phenomenal memory for detail, even of things of which she disapproved’ (perhaps, one is tempted to suggest, particularly of things she disapproved!). According to Philip Jones, she ‘effortlessly dominated the program’. On one occasion, sports broadcaster Eric Welsh was asked to name three winners of the Melbourne Cup with royal names. He could name only two, and jokingly passed the question onto Valentine, a lifelong opponent of gambling, who promptly provided the third. However, when in 1953 she learned that the programme’s prizes were to be sponsored by a lottery, she resigned.

Valentine inherited some of her central convictions from her father. She was always loyal to his Protestant Irish brand of low churchmanship, though, like him, she supported the ordination of women, which might have seemed at odds with it. She opposed liturgical innovation and clung to the Book of Common Prayer. Her sympathy for minorities did not extend to homosexuals; she expressed disgust at ‘the legalisation of buggery’. ‘Metric madness’ incurred her wrath, as did daylight saving and air-conditioning on trains. She treated any issue, great or small, with immense seriousness and argued her case vigorously. ‘I am trying, perhaps unsuccessfully, not to be offensive,’ she told one parish priest when protesting his abandoning the service of Morning Prayer. She herself attributed her confrontational temperament to her Irish Protestant heritage: ‘my instincts are always for the fight-for-a-finish section rather than the compromisers.’

This is a longish book – some 400 pages including several appendices – and it is not without its glitches. Not all women in Great Britain had to wait till 1928 for the vote: women over thirty gained it in 1918. Unaccountably, Sense and Sensibility is attributed to ‘Jane Austin’. But Poynter has done us a service in bringing Valentine Leeper to our attention. Her life was remarkable, not so much for what it achieved, though she had her successes, but for what it represented: combining the role of dutiful daughter and outspoken maverick, she had the satisfaction of making her presence felt.

She was at her best, perhaps, in the cameo performance which Poynter uses to introduce the story. Just after World War II, a distinguished air vice marshall was giving a valedictory address to the final assembly of Melbourne Church of England Girls’ Grammar. Describing the situation in Japan, where there was the prospect of starvation over the coming winter, he added, in a casual aside, that perhaps that was not such a bad thing. Valentine, ‘shabby and goblin-like in nut-brown from head to shoes’, rose to her feet and, to the shock and amazement of the assembled girls, declaimed: ‘That is no way to talk in front of young girls in a Christian school!’ She demanded, and got, an apology. It was vintage Valentine.

Comments powered by CComment