- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

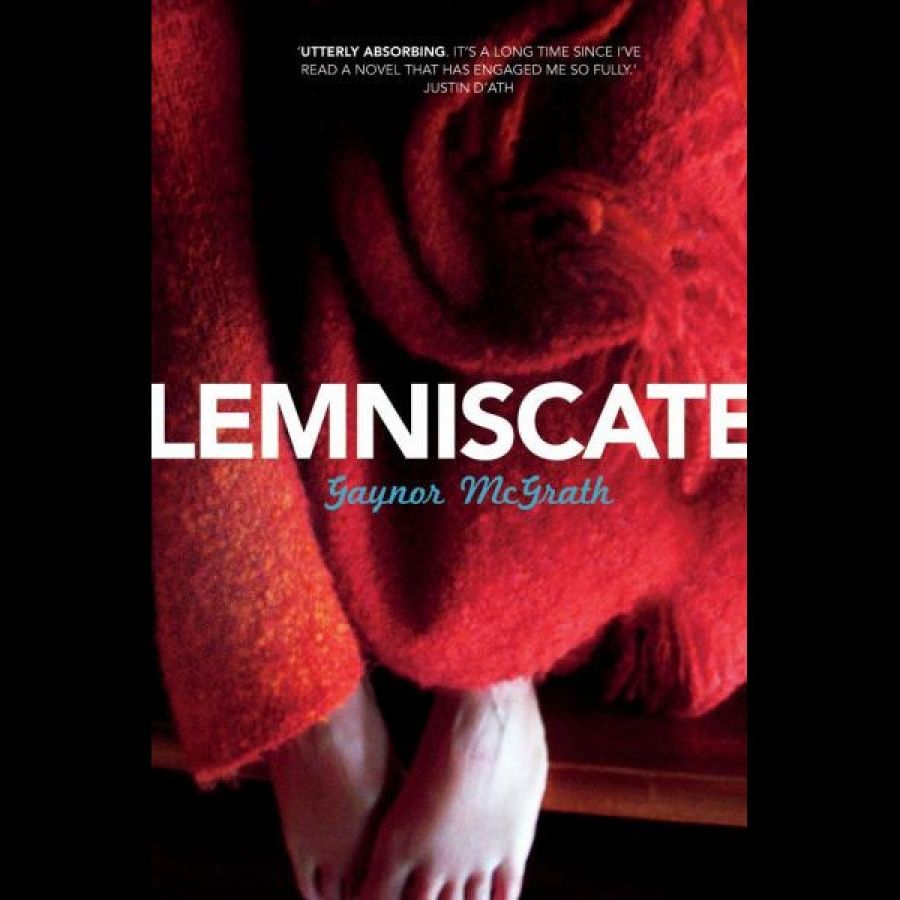

- Book 1 Title: Lemniscate

The structure of the novel consists of Elsie’s restless wanderings and her numerous adventures along the way, as she battles recurring (travel-related) illnesses, benefits from the kindness of strangers, weathers serial overtures (and proposals), and falls in and out of love. The crux of Lemniscate, though, goes to the heart of a deeper, internal journey, as Elsie struggles to overcome a lifetime’s socialisation and discover her true core. Her travels end, temporarily, when she arrives home in Adelaide and must come to terms with the conflict between her former life and the one her wanderings have led her to pursue. Her discomfort with domesticity and her strong aversion to compromise in relationships are pronounced throughout the novel. ‘Part of me always feels detached,’ she muses. ‘I see people needing others ... and I don’t even understand what it means.’ The key strength of Lemniscate is McGrath’s rich description of the people and places Elsie encounters, not just overseas, or on her later travels around Australia, but her pitch-perfect depiction of life at home in Adelaide. In Pakistan, her travel companion Stan whoops with joy among roadside patches of wild marijuana. Back home, at Balfours on Rundle Street, Elsie consumes ‘the lunch [she has] been longing for: a pasty with tomato sauce’. This longing for the prosaic pleasures of home combines with an unsettling dislocation, prompted by the sameness of the world she left behind – and her realisation of all the ways she had never belonged there. Elsie’s thoughtful internal voice processes her experiences, constantly assessing and comparing, drawing on her cross-cultural experience. This is the secondary asset of the book, one that, combined with McGrath’s canny descriptive prowess, places the reader at the nerve centre of an era in transition, from the vantage point of a narrator who is at the frontline of social change. McGrath’s Achilles heel is her dialogue, which can be stilted, even jarringly banal. The first chapter is particularly dialogue-heavy; it takes a while before Lemniscate begins to exert its considerable charms. Similarly, the final quarter of the novel is disconcertingly busy, particularly its final fifty pages. Too much happens and too many new characters are introduced at this late stage, including a new supporting cast and location. However, a heart-breaking event late in the novel is deftly and sensitively drawn.

Lemniscate, like Kerouac’s road novels, is imbued with a sense of lived truth. It is a fascinating evocation of a lost age of travel of a particular kind. In Bali, Elsie says: ‘Everywhere I see evidence of a beautiful, gentle, intricate culture and at the same time I know that my very presence is part of the corruption and ultimate ending of that world.’

More than simply a travel novel, Lemniscate is a meditation on what drives us to travel, how the experience transforms the traveller, and the lessons we can take away from immersing ourselves in other cultures, particularly the experience of seeing our own society through an anthropologist’s eyes on our return.

Elsie concludes that she has found a kinship of sorts, joining

a worldwide network of people who do not quite fit into their own societies: it does not contain any of the comforts and reassurances of earth-bound societies or even the companionship ... it is not a destination of choice but rather a place one ends up in simply by pushing the boundaries.

Comments powered by CComment