- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthologies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

David Malouf, one of the subjects interviewed by Margaret Throsby in Talking with Margaret Throsby, recounts his childhood experiences as an eavesdropper. He reveals that by listening in on conversations between his mother and her women friends he learnt about a world that was otherwise off-limits to him. For devotees of Mornings with Margaret Throsby on ABC Classic FM, the experience might sound familiar as they tune in to live conversations between the host and her distinguished guests; conversations which, although obviously public in that they are broadcast on national radio, frequently open a window onto the private world of the subject. Paul Keating, in Talking with Margaret Throsby, reveals that he would often prepare for cabinet sessions by listening to music (‘Start off slow, you know, and finish on something big’), conductor Jeffrey Tate discusses the ways in which he has coped with spina bifida, and writer and restaurateur Pauline Nguyen, who arrived in Australia as a ‘boat person’, talks about the difficulties of growing up in a household marked by fear and violence.

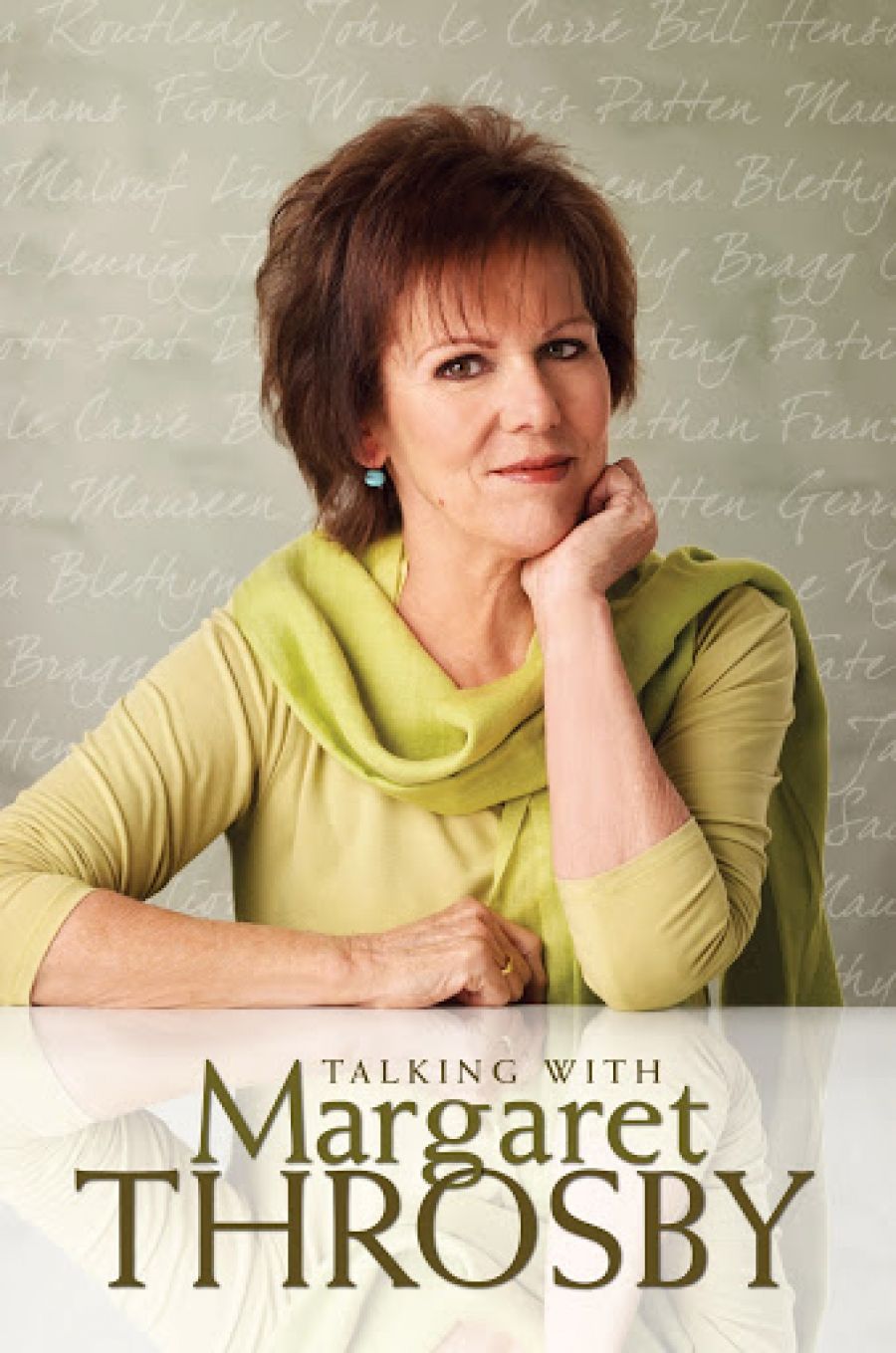

- Book 1 Title: Talking With Margaret Throsby

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.95 pb, 384 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/rV1YQ

Throsby’s formula is a simple one: guests choose pieces of music that are of special significance to them – on the basis of these transcripts, five seems to be the limit – which are then used to pepper the conversation. The first musical work in each interview functions as an ice breaker (the guest is invited to explain the reason for the choice), but subsequent works tend to act as convenient interruptions from the chatter and are usually not afforded much attention. (For the record: the most represented composer in Talking with Margaret Throsby is Schubert, followed by Mozart and Beethoven; Ry Cooder and Leonard Cohen also make repeat appearances.) Throsby’s principal aim is to have subjects talk about their lives, work, ambitions, influences and personal philosophies. Now and then she narrows the focus somewhat. Much of the interview with Fiona Wood, plastic surgeon and 2005 Australian of the Year, is a discussion of the response of her team in the burns unit at Royal Perth Hospital to the Bali bombings of 2002; and mountaineer Lincoln Hall speaks almost exclusively about the experience of nearly perishing on Mount Everest in 2006.

But while Throsby’s formula is relatively simple, the results vary from one interview to the next. Most often the conversations chart a course of the interviewer’s choosing, which is not to say that the journey is always smooth, or that hazards are averted. One of the most successful chapters is Throsby’s 2005 interview with former Hong Kong governor and current member of the House of Lords, Chris Patten. It is a seamless dialogue that offers a satisfying mix of political memoir, political commentary, personal history and personal viewpoint. Gravity and levity are neatly counterpoised and Patten’s musical choices are skilfully worked into the conversation. On every level it stands as an exemplar of its kind (the same could be said of Throsby’s interviews with Billy Bragg, John le Carré, Keating and Tate).

Throsby’s 2003 interview with photographer Bill Henson, on the other hand, is, technically speaking, a bit of a mess. It is not so much a dialogue but a series of exchanges in which the interviewer appears unable to grasp fully the points being made by the interviewee. It is all the more remarkable, then, that Henson comes across as a deeply thoughtful individual and a man who has long pondered the intricacies of the ties that bind artist, artwork and art consumer. As an interview, it is hardly Throsby’s finest hour, but we are afforded some terrific insights into her interlocutor.

In fact, given that Throsby’s aim is not to grill her guests, it is especially impressive that the interviews occasionally offer moments of sagacious profundity. Nevertheless, I would have liked more depth from her conversations with author Jonathan Franzen and journalist Maureen Dowd. And it is truly cringe-inducing to encounter Throsby asking the latter which of the US presidents that she has written about in her professional life she have fallen in love with. Not only is the question sexist, it demeans both interviewer and interviewee. Dowd is evidently taken aback by Throsby’s insistence upon a reply.

The stand-alone nature of each interview means that the chapters can be read in any sequence, but it is fascinating to follow them in the chronological order in which they are presented. Throsby’s interview with Patten, a one-time parliamentary under-secretary of state, Northern Ireland office, happens to be placed near her conversation with Gerry Adams. Wood discusses the life-saving aspects of plastic surgery while, a chapter or two later, Dowd ridicules its more frivolous applications. Nguyen describes her family’s clandestine escape from Saigon, while Michael Leunig, in the following interview, mentions that he was in the first call-up to fight in Vietnam but failed the medical. The lapse between the interview date and the present also provides the odd surprise. Le Carré’s reference in February 2001 to the Bush administration’s incursions into Central America thoughtfully reminds us of US foreign policy priorities in the pre-9/11 world, and it was especially interesting to discover Keating’s choice of the nation’s top domestic issue and the item at the head of his agenda had he remained in government: restoration of the Murray-Darling basin. The Keating interview took place in 2000.

Comments powered by CComment