- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sonya Hartnett is one of the most various of good writers. In particular, she is good at creating atmosphere: a distinctive world for every story. As a consequence, every book she writes is a different style of book. Take some recent examples. The Ghost’s Child (2007), with its plot like a fable, reads like an old tale told in an outdated language of ‘sou’westers’ and ‘fays’. Its form, language and style are so consistent its oddity seems like part of its simplicity. In contrast, Surrender (2005), a horror story, has a style of calculated Gothic, playing narrative games to manufacture menace.

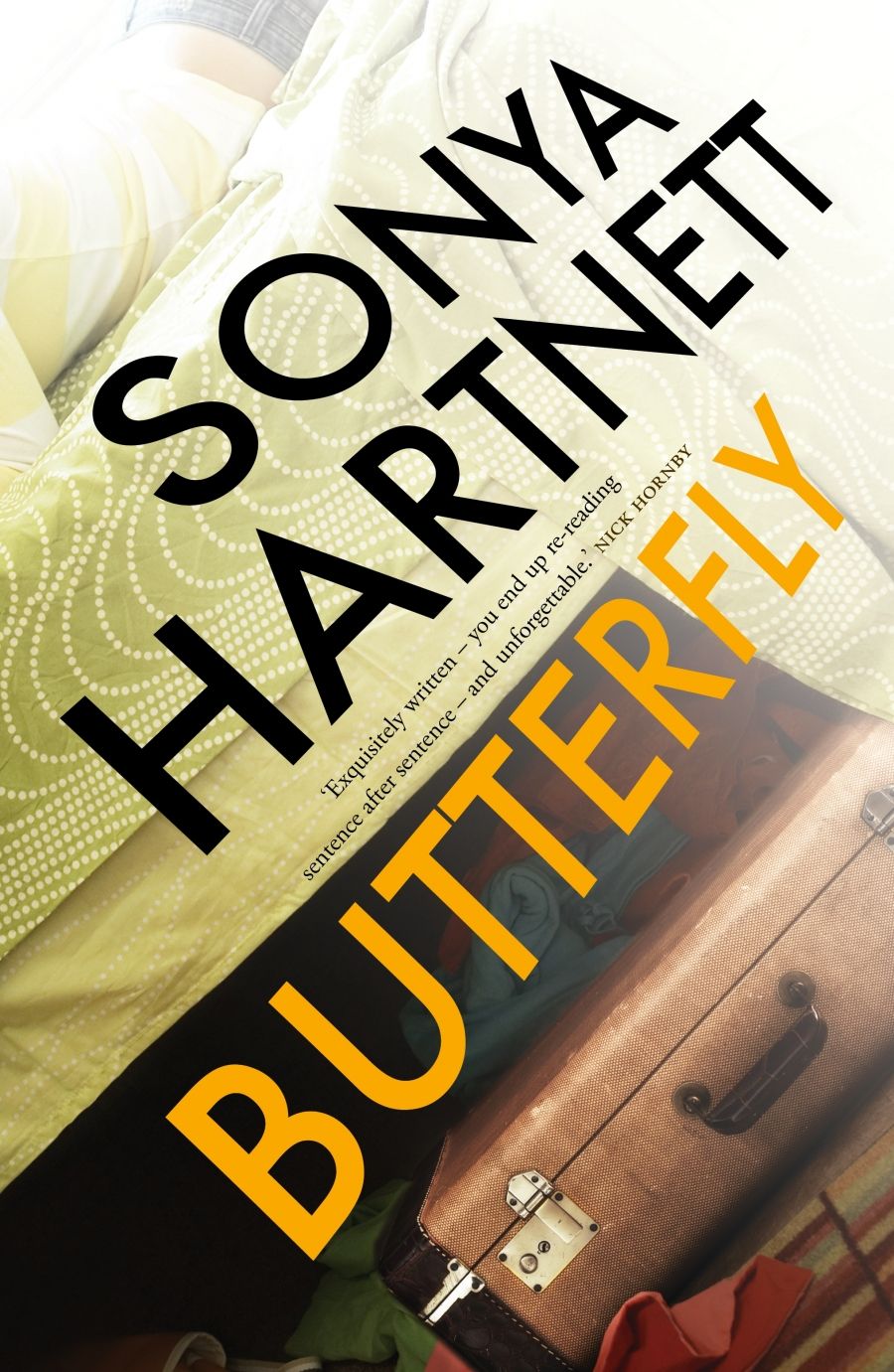

- Book 1 Title: Butterfly

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $29.95 pb, 224 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/AJV0R

Plum has posters of David Bowie and kittens on her wall. Silly, hopeful and fierce, she spends most of the novel trying to manage the uncertain alliances that pass for school friendships. Plum is determined to become a new person, beautiful and loved; she puts her faith in her coming birthday party and in the advice of a glamorous neighbour.

Butterfly is a novel full of things. Plum’s neighbour Maureen fusses over décor. Her parents, Mums and Fa, collect old furniture. Justin tinkers with his car. Cydar collects rare fish. Plum trusts in the collection of talismans she keeps in a suitcase under her bed: a crystal lamb, a yo-yo, a penny, a pendant and a broken watch. All these characters work at life in the realist style, crowding it with things; but for Hartnett, what is real is what is irrevocable. For all its involving detail, its gossipy readability, Butterfly is disquieting and memorably strange.

In 2008, Hartnett won the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, the world’s biggest prize for children’s literature. For years she has resisted the claim that she writes for children. However, Butterfly shows how well she writes about children. In Plum, Hartnett captures the queasy ambition and self-loathing of adolescence, the self-obsession that is a version of social obtuseness. This is the central part of the novel, and its main achievement.

In fact, for all its realism, Butterfly may be Hartnett’s most subtly audacious novel. Written in the third person, for the most part it shows Plum’s point of view: not only detailing her activities but also holding to her ignorance and her enthusiasms. For instance, Plum has a ‘growing conviction that … a parent should be a person the way a door is a door, something like the robot in Lost in Space – loving and providing and cleaning, not distracted by wishes and needs …’ Because of this, Mums and Fa hardly exist as characters. On the other hand, the novel details Plum’s lunchtime conversations with her gang of friends: what they think of their teachers; what they like in their sandwiches. In this way, Butterfly has odd gaps and emphases, reflecting Plum’s preoccupations. It is a shapely, beautifully paced story that captures the awkwardness and ferocity of adolescence.

From time to time, Butterfly tells part of the story from another character’s point of view. There is Maureen, the glamorous neighbour: it turns out she is sleeping with Plum’s older brother, Justin. And there is Plum’s other brother, Cydar: stoned, remote, observant, and more loving than he seems. Their perspective allows a reader to measure how much Plum misses. In this way, the narrative in Butterfly works like one of the objects that it describes: a curio that Justin keeps and Cydar values.

On the chest of drawers is a shallow bowl that has a rotating base. The interior of the bowl is divided into six compartments, each with its own flip-top lid. The lids are inscribed in copperplate: cuff links, rubber bands, spare change; paper clips, safety pins, keys. A manly ornament from two decades earlier that attracts Cydar like fireworks. He spins the bowl, the lids whirl around – then stops it sharply with a jabbing finger. Paper clips. Lifting the lid reveals not paper clips but a purple button entangled in cotton …

This curio serves as an emblem of the way this novel spins to reveal different points of view: characters existing separately, keeping secrets. Such a play of perspective complicates how it feels to read Butterfly. If, for the most part, we see what is happening from Plum’s point of view, we also feel how she skews the story. In this way, reading Butterfly is like experiencing one of the anxieties that defines Plum’s adolescence: that the main story is happening elsewhere, without her. In two of Hartnett’s other novels, Of a Boy (2002) and Surrender, the ending changes the meaning of all that has happened in the story. In Butterfly, the ending changes even what kind of story it is. Its ending makes Butterfly a painstaking study of consequences: how oddly they link to causes when the causes seem like ends in themselves.

Comments powered by CComment