- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I will always remember the first time I heard Kim Beazley Sr speak. It was at Kingswood College at the University of Western Australia, a year or two before the election of the Whitlam government. He spoke on the question of Aboriginal land rights, culture and spirituality. It was a spellbinding address which put the sword to the prevailing doctrine of assimilation. It wasn’t just the content of the speech which captured the interest of the student audience but the passion with which it was delivered. Like many there, my own thinking on the subject changed forever.

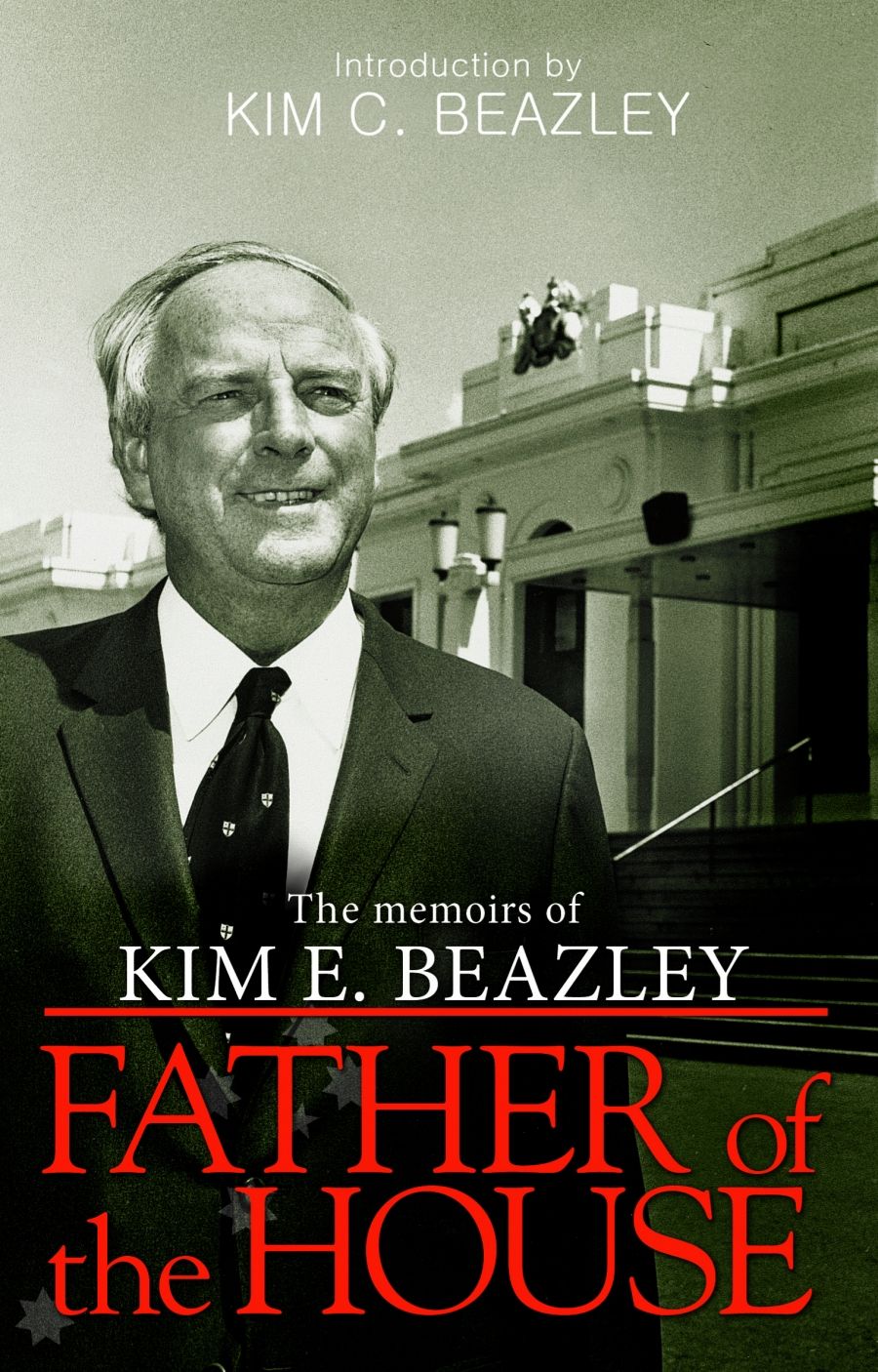

- Book 1 Title: Father Of The House

- Book 1 Subtitle: The memoirs of Kim E. Beazley

- Book 1 Biblio: Fremantle Press, $27.95 pb, 335 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/WmLx3

Father of the House: The Memoirs of Kim E. Beazley is not your normal political memoir. It is reflective and it is philosophical. In it he illustrates the role and importance of religion and ideas in politics, but despairs that, all too often, they take second place to vested interests and personalities. The book tells us much about Beazley’s achievements as a citizen and MP, but it is not a case study in self-justification. Indeed, he describes his walk-out from the 1955 Labor Party Conference in Hobart as ‘the biggest mistake’ of his parliamentary career. He believes that the split in Labor may have been averted and that, by withdrawing over a procedural issue, he gave up any chance he had to prevent it happening. So too he thought foolish the decision of those who opposed communist influence in Labor to form a new political party. This conclusion takes us to the heart of Beazley’s politics and his vision of Labor as a coalition of social democrats and social conservatives. He was both, but for many of his colleagues to the left or the right it was a case of ‘either/or’.

For Beazley, the seeds were sowed early by a deeply religious mother for whom Christianity was a call to action as well as a call to prayer. Beazley tells of being torn between Marxism and Christianity while at the University of Western Australia in the 1930s. Christianity won the battle, as indeed it had done in the British and Australian Labour Parties in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Beazley could not accept the concept of the class war and what it meant for the means and ends of politics. Politics, like life, needed a transcendental element taking us beyond individual, class and national interests. This was provided by the moral code of the Judaeo-Christian tradition which, he observed, also had much in common with world religions, Confucianism and Aboriginal culture.

In many ways, Father of the House is a personal account of the relationship between politics and religion as seen through the eyes of a believer. Beazley dwells on the powerful influences of ‘conscience’ and ‘reconciliation’ as driving forces in politics. He reveals his debt to Christian activists such as William Wilberforce and Lord Shaftesbury. He concludes that ‘civilisation only advances when individual consciences become more sensitive to the needs of others’. He is fully aware of the tensions that can emerge in a less than perfect society between ‘being political’ and ‘taking a stand for justice’, and notes his own failings in this regard, particularly in relation to attitudes to Japan in the immediate postwar period.

This takes me to his commitment to Moral ReArmament and its belief in the power of reconciliation. Beazley speaks openly of his conversion experience at MRA’s headquarters in Caux, Switzerland, in 1953. He explains that it lifted both his Christianity (the goal of absolute purity) and his politics (the goal of honesty) to new heights. ‘For me,’ he writes, ‘honesty meant a decision that I would not play the political game of making cases, suppressing everything inconvenient to my position and playing up everything convenient.’ What matters is not who is right but what is right. He worried too much about the personal and social consequences of power ever to be one of its greatest exponents.

In the book, Beazley provides many examples of the limitations of power politics and the liberating impact of reconciliation. He also explains that, despite his opposition to communism as a guide to action, he understands the reasons why people became communist in a world of racism, colonialism and social inequality. For example, he speaks highly of Patrick Troy, his communist adversary in Fremantle, for his honesty and dedication to the working class.

It is the question of how to tackle injustice that takes up a large part of the book. Beazley is most perceptive on issues related to education in general and Aboriginal disadvantage in particular. The chapters on these subjects are provocative and relevant to the debates today. He defends Aboriginal culture and spirituality, and reaffirms his support for bilingual education, but he is highly critical of much that has been done in their name. He describes the frustrations he felt as a reforming minister in the face of a government education system ill equipped to deal with the twin challenges of difference and inequality. He saw Commonwealth involvement on the basis of the needs principle as a lever for a fairer system overall and better and more effective practices in the schools themselves.

Beazley is not afraid to defend public expenditure as an instrument for social progress. All too often in Australia, he says, we assume that whatever is done for the poor will add to the deficit and whatever is done for the rich will increase the return on the investment. For Beazley, John Kenneth Galbraith (whom he quotes approvingly), rather than Milton Friedman, provides the best text for public policy. ‘The focus on economic rationalism,’ he says, ‘is creating a cynical society where many people have lost the generosity on which community depends.’

There is much in the book about Australia’s successes and failures in understanding the passing of the colonial era in the Asia-Pacific. As early as 1956, he was expressing the view that Australia’s stability will be determined by the extent to which it earns the respect of Asia. All too often, however, our ability to contribute to peaceful and progressive solutions was marred by prevailing assumptions of white superiority and persistent attempts to subordinate the Asian people to our material interests. His reflections on Vietnam, Papua New Guinea and East Timor are priceless.

Of particular interest to students of Australian history are his references to the major figures in postwar politics – Curtin, Chifley, Evatt, Calwell and Whitlam on the Labor side, and Menzies, Holt, Hasluck, Gorton and Fraser on the Liberal side. His judgements on each are thoughtful and balanced. Not surprisingly, he has a good deal to say about his fellow Western Australian Paul Hasluck, who, he says, ‘came nearer than anyone I know to putting the needs of the country, as he saw it, before party considerations’.

Perhaps not surprising is the absence of any reference to the republic debate. Beazley remained steadfast in his support for parliamentary government and the Australian Constitution. He notes, however, that we ‘too easily take for granted’ its smooth functioning, and he is highly critical of Malcom Fraser for overriding parliamentary conventions to force an election in 1975. Sir John Kerr is also criticised for not attempting to mediate a way out of the crisis: ‘He exercised political power and, in so doing, undermined the office of Governor-General.’

One cannot help but feel that it was the split in the Labor Party that was Beazley’s greatest disappointment. He applauded the brilliance of the Whitlam leadership in bringing Catholic voters back into the fold with his needs principle in education, but was never comfortable with his left liberalism and the law reform agenda that came with it. Beazley was a social conservative who could not support family law and abortion law reform. Nor was he comfortable with the privatisation and user-pays agenda of the 1990s. This being said, he remained loyal to the Labor Party and with his wife, Betty, was a stalwart of the Cottesloe Branch right to the end of his life (he died in October 2007). ‘In my thirty-two years in parliament,’ he observed, ‘though I was sometimes forced to vote against my judgement I was never forced to vote against my conscience.’

Comments powered by CComment