- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Tucked inside a plastic sleeve affixed to the inside front cover of this handsome, large-format book is a video disc promising ‘The Best of Graham Kennedy’. Introduced by Stuart Wagstaff, the one hour of footage offers a compilation of Kennedy’s work for Channel Nine drawn from the early days of In Melbourne Tonight (1957–69) and The Graham Kennedy Show (1972–75). Most of the sketches, dance routines, advertising segments and encounters with the audience I had seen before. Rover the Wonder Dog peeing on a camera while refusing to spruik Pal dog food has become part of the collective memory of Kennedy’s contrived mayhem, revisited whenever television (especially Channel Nine) embarks on one of those moments of self-memorialisation with which it marks each milestone.

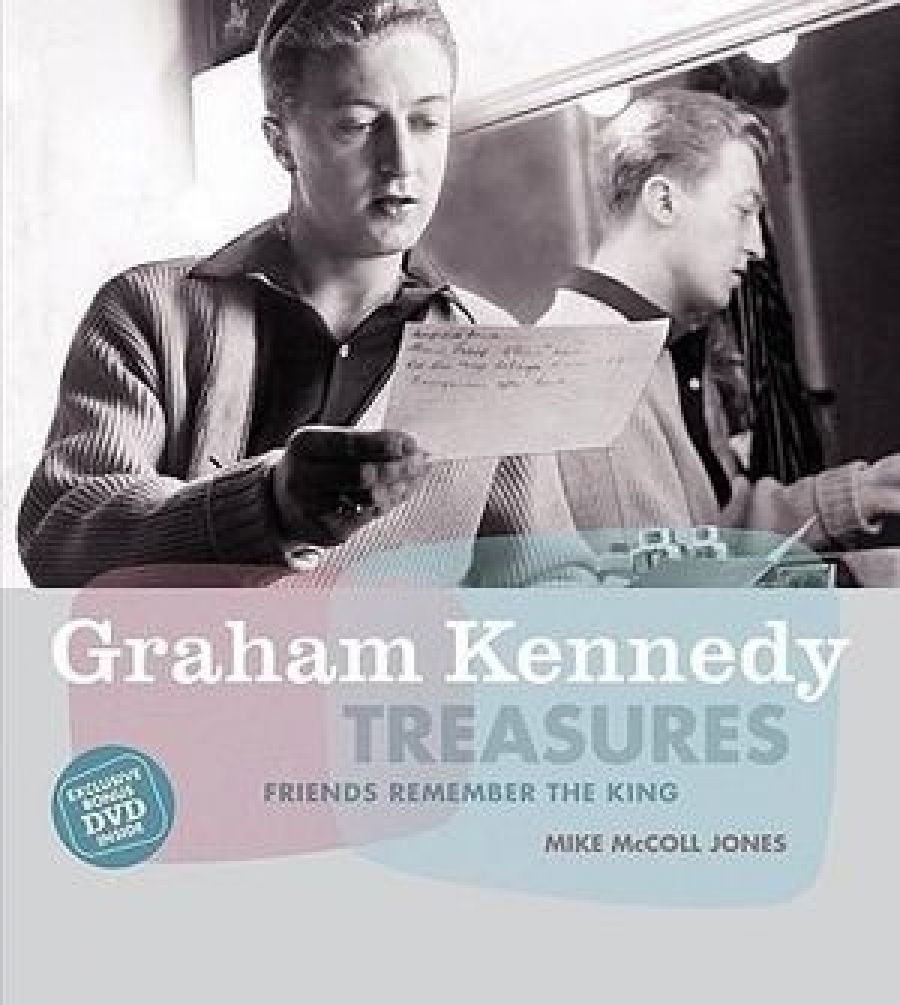

- Book 1 Title: Graham Kennedy Treasures

- Book 1 Subtitle: Friends remember the king

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah, $64.99 hb, 272 pp

According to Mike McColl Jones, Kennedy’s former scriptwriter, things probably were going exactly according to Kennedy’s plan, although whether Sturgess was privy to it is another matter. One of Kennedy’s comic tactics was to take everyone by surprise, including himself.

One of the ‘Grahams’ which emerges from McColl Jones’s lavish tribute in words and images to his ‘mentor, colleague’ and ‘funny friend’ is the meticulous and obsessive performer whose talent lay in making the carefully rehearsed look entirely impromptu. As testimony, McColl Jones offers an account of the daily ritual of IMT on a page facing a photograph of himself and Kennedy from the early years. The shot is revealing. McColl Jones is looking at Kennedy, while Kennedy returns the gaze of the camera with those ‘oyster blue eyes’. Kennedy usually knew when he was ‘on’. McColl Jones has eyes only for Kennedy, as did we.

According to McColl Jones, each night at about seven p.m. Kennedy would be given a script with his opening remarks. He would then ‘studiously alter phrases and words, and carefully print the changes in by hand. He would then mark his running sheet with key words and phrases, even to when he might change after a sketch and into what outfit.’ As evidence, McColl Jones includes a page of gags which Kennedy has annotated in his neat, cursive handwriting with comments such as ‘OK but blue’. This reflects back on an earlier epigraph from fellow comedy writer Tony Sattler to the effect that Kennedy was a prude and that his naughty boy persona was an elaborate façade. Further down the same page, Kennedy the consummate comedian who knows his craft inside out appears. Rejecting a gag as ‘too contrived’, Kennedy notes in the margin, ‘The comparison gag which usually ends “and that was only” is always good, but for use only once in a routine!’

Graham Kennedy Treasures does not set out to be an exhaustive, chronological biography of its subject. As McColl Jones appreciatively notes, that work has already been done by Graeme Blundell (King: The life and comedy of Graham Kennedy, 2003). What McColl Jones offers, instead, is a ‘personal record of a man I worked with, journeyed with, laughed and cried with, stood in awe of, learned so much from, got into trouble with so many times, and loved’. His source material includes Blundell, but also the insights and anecdotes of other friends and colleagues who knew Kennedy well. It is these anecdotes and insights, especially his own, with which McColl Jones illustrates the various stages in Kennedy’s career, and they are revealing. More revealing indeed than the many photographs in which Kennedy has carefully composed himself for the gaze of the camera, although if the book had been arranged differently this might not have been the case.

If I have one criticism to make of this otherwise insightful book, it is the separation of the text from the images with which it should have been in dialogue. Take an early section which discusses ‘The Private Graham Kennedy’: the Kennedy who hated being ‘on’ for strangers. If only this had been accompanied by one of the few photographs in which Kennedy does not appear to be aware of the camera. In this particular colour image, which spans two pages, Kennedy is sitting in a chair in a blacked out rehearsal space. His feet are up and his hands resting in his lap. His check jacket is slung over the back of the chair. His shirt is open at the neck. Sunglasses mask his eyes. This is not the Kennedy the television audience knows. It does not even look like him, because the Kennedy we know is always animated, even when frozen in a photograph. McColl Jones’s caption reads ‘The calm prior to the nightly IMT storm’.

Apparently, the calm was as much a part of Kennedy as the ensuing storm, except all the audience ever saw was the storm. Away from the camera, Kennedy was a different man: intensely private, insecure, possibly unhappy, possibly lonely. At least this is the way the 2007 telemovie, The King, portrayed Kennedy; in depressing sepia tones, with an emphasis on his repressed homosexuality as a quasi-diagnosis. McColl Jones eschews neat conclusions. While he acknowledges Kennedy’s reclusiveness, another private Kennedy is revealed.

This is the Kennedy who enjoyed food, wine, Broadway musicals, making jam, collecting lamps and purloined Qantas Wedgwood china: a collection probably added to while taking an impromptu Christmas Day Qantas trip to New Zealand with his chum Stuart Wagstaff. According to Wagstaff, the pair enjoyed a raring good time in first class, spending two hours in Auckland airport buying ridiculous presents for each other, before heading back onto the plane for another riotous trip back to Sydney with the same accommodating crew. It is anecdotes such as these which suggest not the sad clown but the man with a sense of humour who enjoyed the company of select friends and the breaking with convention, even off camera.

In vivid snapshots, both visual and verbal, a contradictory and complex Kennedy emerges from these pages. McColl Jones’s Graham Kennedy is the man who made people laugh, who took Rosie Sturgess by surprise, who endeared himself to a nation in the process, and who ran away to a farm called ‘Clydesdale’ with the giant work horses he had loved since he was a boy in working-class Balaclava, Melbourne, sent out to collect their manure for the garden.

‘For such huge animals,’ writes Kennedy in an essay reprinted here, ‘they are surprisingly timid and gentle and quite affectionate once they get to know you.’ Thanks to McColl Jones, the affinity between Kennedy and the Clydesdales becomes apparent. Kennedy, however, was much funnier.

Comments powered by CComment