- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australian conservatism, for all its political dominance, is little understood and has been studied by surprisingly few scholars. The very industrious and perceptive Peter van Onselen is almost single-handedly determined to correct this imbalance. He has brought together a timely collection of essays on the Liberal Party and its future, coinciding with yet another term in unaccustomed opposition, an experience invariably chastising for the conservatives. The immediate predecessors to the modern-day Liberal Party on the non-Labor side of politics disintegrated on losing office, and the Liberal Party’s own spells in opposition have been periods of both blood-letting and soul searching. There is a happy focus (for the Liberal Party, at least) on the latter in this necessarily mixed bag.

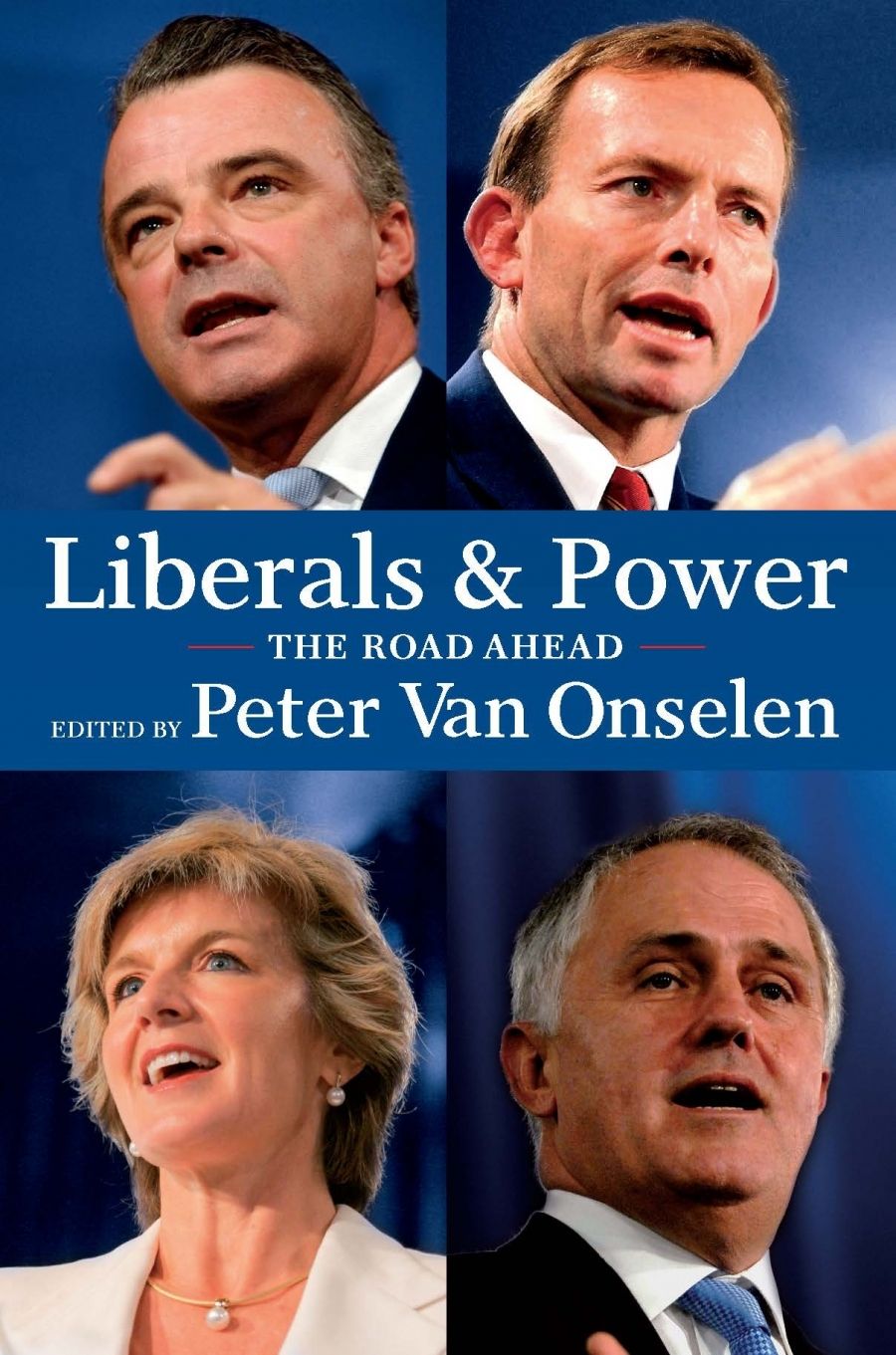

- Book 1 Title: Liberals and Power

- Book 1 Subtitle: The road ahead

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $36.99 pb, 280 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/zL5EO

The collection is not without controversy. For example, Ainslie van Onselen boldly urges the Liberal Party to address its gender imbalance by a quota system, similar to the Labor Party, an idea that is anathema to most Liberals. There is controversy of another sort: the absence of any contribution from current party leader, Malcolm Turnbull, and a ghost-written chapter on industrial relations from current deputy leader, Julie Bishop, which turns out to be based on a decade-old speech by a New Zealand businessman. An anodyne offering from former leader Brendan Nelson proves to be the work of one of his staffers. Turnbull was invited to contribute, but offered only a post-budget speech to the National Press Club on, of all things, the Labor Party’s performance in government. It was politely rejected.

Editor van Onselen has been rightly scathing in his response, publicly reproving the three most senior members of the party for not addressing the party’s future, especially at a time of its nadir, when it is out of government everywhere except in one state. This raises the question of the extent to which the Liberal Party is interested in any ideas at all, other than finding its way back into government; it is the time-honoured anti-intellectualism of the right reasserting itself in modern guise.

But there are others who take the battleground of ideas seriously, and sparkling, provocative and thoughtful chapters from the formidable Tony Abbott, the seriously underrated George Brandis and columnist Janet Albrechtsen provide a solid backbone to the volume and make it essential reading for anyone with an interest in the current state of play in Australian politics.

Many writers here make reference to a common enemy, ‘the left’. But is there really a left any more in Australian political life? To what extent, if any, is it useful to characterise the Labor Party as leftist? Too often this straw man is invoked for rhetorical effect, but just who he is or what he represents is far from clear. Is it simply those political forces that oppose the Liberal Party, or even more specifically, John Howard, that are lumped together as ‘the left’? I find it difficult to regard a party that has embraced the neo-liberal capitalist ethos as enthusiastically as the ALP has as left in any real sense. The only way in which it makes sense, in the contexts in which it is used here, is as a check or balance on the drift of upward redistribution of wealth, which is the hallmark of the neo-liberal paradigm. In this sense, the ALP might just, only just, marginally qualify – but it does stretch a point.

Robert Manne, as always, offers a substantial contribution, setting the scene for what is to follow, and in doing so he neatly articulates a major theme, albeit a paradox, in that a collection about the future of the Liberals is so concerned with the immediate past in the form of Howard. In fact, Howard’s shadow looms large over the entire volume. Manne correctly credits Howard with changing not just the Liberal Party but Australian political culture itself; he identifies a defining characteristic as Howard’s populist conservatism.

Manne finds ‘scandalous behaviour’ in Howard’s persistent rejection of the Kyoto Protocol and global warming in general, and in the process identifies the very un-Australian brand of neo-liberalism that Howard sought to impose: a profound mistrust of government and an ideological propensity to interpret all expressions of doubt about the beneficence of the workings of the free market as the deep anti-capitalist prejudices of politically correct élites.

Certainly, a problem for latter-day conservatives – in particular Howard, with his infusion of neo-liberalism and his preoccupation with the ‘culture wars’ – is the matter of the state in the Australian political ethos. Calls for small government, which started to appear in the 1970s under Fraser, and were amplified in the 1990s under Howard, fell on barren ground: there was simply no anti-state sentiment as a general current in Australia. It was firmly established in colonial time that governments alone could provide the services and utilities necessary for development, such as irrigation and railways. Nor was this seen as anomalous: indeed, it was widely accepted that this was the proper role of government. The colonial political experience in Australia was essentially collectivist, not individualistic; the whole derivation of ‘mateship’ in the Australian ethos is a celebration of collectivist triumph over adversity.

Abbott provides a staunch, if tendentious, defence of Howard and his legacy, and therein lies an implied warning for Turnbull in his efforts to reposition the Liberal Party. Abbott, however, is not blind to the need to win back the ‘moral middle class’ which cooled towards Howard; especially in regard to the republic and multiculturalism, but he stops short of offering a blueprint.

The cerebral Brandis, in the standout essay here, takes his forensic scalpel to Howard’s conservatism, noting how Howard liked to publicly identify with Robert Menzies but in fact represented a radical departure from the latter’s Deakinite social liberalism. In carefully chosen words, Brandis condemns Howard’s selective view of liberalism’s much vaunted regard for human rights, noting lapses in regard to the treatment of people held in immigration detention centres, multiculturalism, the encroachment of antiterrorism laws on traditional freedoms and immunities, and discrimination against same-sex couples. Howard took the party and the country down a path of economic deregulation which, while providing alleged long-term benefits, removed traditional protections and created uncertainty in the short term. Howard, notes Brandis, was a bundle of contradictions; principles sacred to Menzean liberalism were too often sacrificed in the name of social cohesion.

Albrechtsen finds all not well with the Liberal Party. She doubts whether the solutions offered by moderates (less conservatism) and conservatives (more conservatism) are any sort of solutions at all. Locking conservatism into its sceptical view of human nature, Albrechtsen writes that the Liberals must cater to a side of human nature that has been long neglected. The party has been so busy dominating the rational low ground that it has abandoned the high moral ground, leaving the left (whoever that might be) to dominate that terrain. Howard, she notes, has overseen not just a transformation of the Australian economy but even one of the Labor Party, which now has ministerial portfolios of small business, independent contractors and the service economy.

Brett Mason also invokes that mysterious left. He identifies two challenges for the Liberal Party: to avoid complacency (which is rather hard in opposition) and to defend the Liberal agenda against ‘impostors and adversaries’. Labor has not changed, he argues; if it had, it would have become a Liberal Party. Some might argue that it has.

David Flint is his usual immoderate self, railing against ‘the élites’, and making the extraordinary opening remark that the Liberal Party has never been an ideological party. In a footnote, he seeks to explain this by redefining ideological as ‘a belief that is not part of and alien to the values held by mainstream Australians’. One can only assume he has not yet come across neo-liberalism and its wanton abandonment of the fair go.

Comments powered by CComment