- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Rediscovering Hanrahan

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The career of one of Australia’s most talented novelists, Barbara Hanrahan (1939–91), was cut short by illness, and her work has now largely slipped from view. I edited several of her novels in the late 1970s for the University of Queensland Press. Whereas other UQP authors of the time, such as the gregarious Olga Masters, enjoyed media attention, with the introspective Barbara Hanrahan it was a struggle to build the readership her talent deserved.

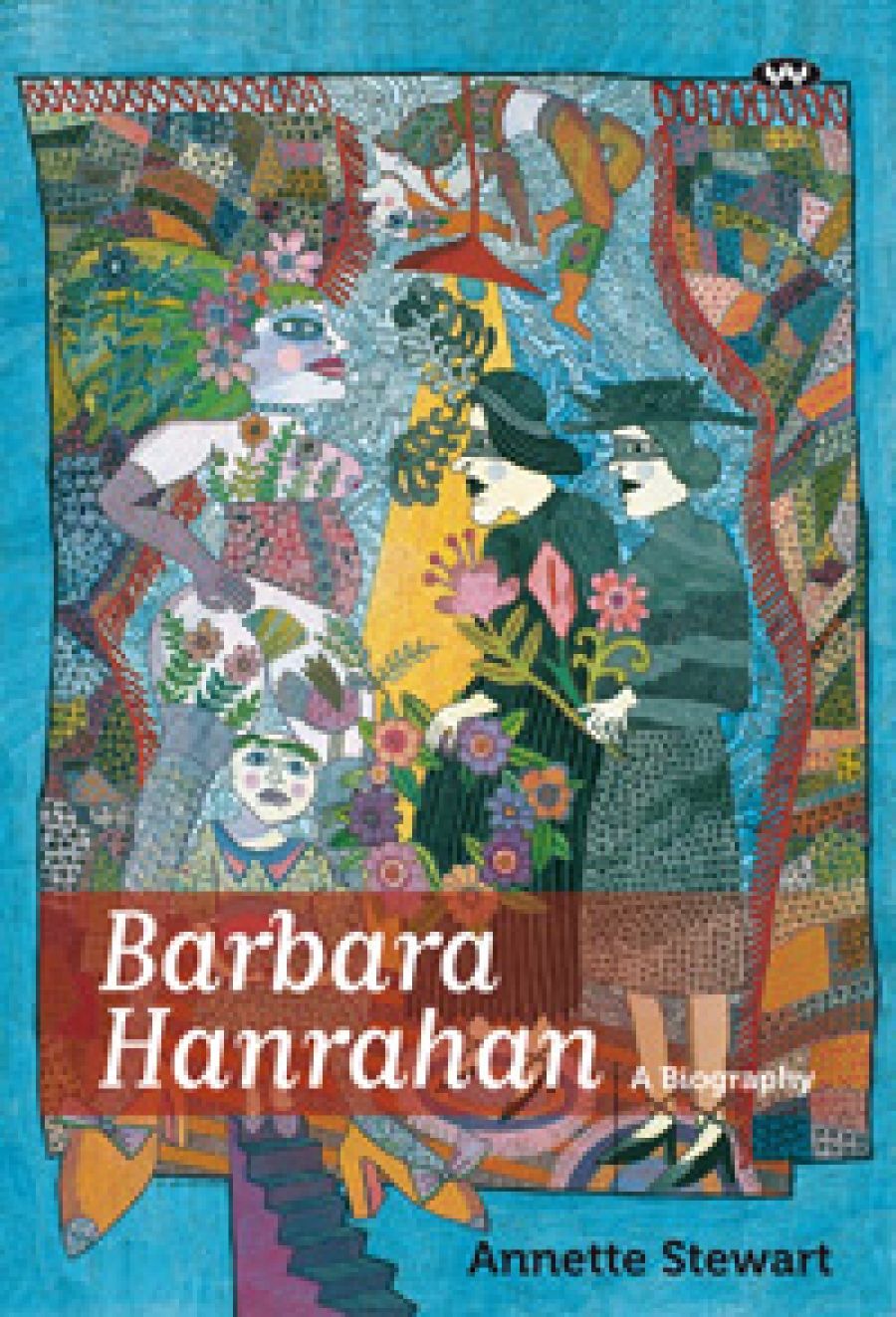

- Book 1 Title: Barbara Hanrahan

- Book 1 Subtitle: A biography

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $39.95 pb, 244 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Born in the same year as Germaine Greer, Barbara Hanrahan began expressing, through her art, similarly confronting ideas about the repression of women. She grew up in Adelaide in a family of women, with her mother Ronda, grandmother Iris (Nan) and great-aunt Reece, who had Down syndrome. Her father, Bob, died of tuberculosis when Barbara was one year old. He became for her ‘the father who never was’, haunting her with thoughts of death.

Ronda responded to her young daughter’s curiosity about Bob with stories and snapshots of this handsome larrikin. Nicknamed the Czar, he had frequented pubs and had been known to turn cartwheels in front of oncoming trams. On his wedding day he went off to play football; later he took little interest in baby Barbara. None of this stopped her from idolising him. Her capacity for fantasy was boundless. While still young she cultivated two opposing personalities: a false social self and a wild spirit self. As an indulged only child, she became increasingly self-absorbed, disturbed and depressed, especially after her mother remarried and landed her with unwelcome stepsisters.

In her teens, Barbara formed a deep attachment to her music teacher. This hunger for mentors led her on a lifelong quest to commune with artists and writers she admired, such as Van Gogh, William Blake, Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence, and Katherine Mansfield. All had suffered for their art, while Lawrence and Mansfield had, like her father, died of tuberculosis.

Perhaps reflecting her own split personality, Barbara came to regard Adelaide as a divided city. There was the ugly, everyday working-class world she knew and the fantasy realm of wealth and privilege. According to Stewart, this class divide underlies all her fiction.

After studying and teaching art in Adelaide and struggling with depression and isolation, Barbara left in 1963 to continue her art studies in London. She endured several unhappy love affairs and an abortion before finding another wild spirit who had cut loose from Adelaide: Jo Steele, an engineer, inventor and motor-racing driver. A risk-taker like Bob Hanrahan, Jo had been tormented by his tyrannical upper-class father, who had left him with an incurable aversion to marriage and children. This brought him into conflict with Barbara, although their relationship ultimately became close and sustaining. The example of the exiled Lawrence and his wife, Frieda, encouraged Barbara and Jo to seal themselves off from the world, without newspapers or television. ‘Barbara’s books became replacements for the children she never had’, Stewart observes.

Since puberty, Barbara had suffered uncontrollable tantrums brought on by mood swings. The news of her beloved Nan’s death led her to seek treatment in London for severe depression. She also began writing in her diary about her Adelaide childhood. Finally in 1971, at the age of thirty-two, she bought a typewriter and began writing her intensely imaginative works of autobiographical fiction.

Initially, her writing was less spontaneous than her printmaking, because she was overawed by her literary models, a daunting circle which expanded to include Jean Rhys, Carson McCullers, William Faulkner, Sylvia Plath and Janet Frame among others. Yet she still managed to develop her own distinctive approach to writing, often using a tape recorder with friends and acquaintances to gather raw material for her fiction. Like Patrick White, she exposed the extraordinary lurking just behind the ordinary.

Hanrahan’s obsession with her childhood began to trouble some critics and finally led to a break with her London publishers, Chatto. Her desperate wish to be accepted by the London literary Establishment continued even after UQP began enthusiastically publishing her in Australia. At this time, she and Jo returned from exile to live once more in Adelaide.

With the Gothic Albatross Muff (1978), she entered her finest phase as a writer, followed within four short years by Where the Queens All Strayed (1978), The Peach Groves (1979), Frangipani Gardens (1980) and Dove (1982). As her editor on three of these novels, I well remember the perfectionism of her manuscripts, every word and piece of punctuation carefully chosen. I encouraged her not only to illustrate the covers of her unusual novels but also to create small drawings to decorate the text, thereby combining her visual and literary artistry. ‘To her,’ writes Stewart, ‘the written page was a visual palette’ and her writing and printmaking ‘began to reflect one another’.

Fascinated by the sexual life of the Victorian era, Barbara often represented women in her prints in the ‘postures of birth and sexual surrender’. Stewart conveys the confronting nature of the print Birth very graphically: ‘The woman’s legs are raised as in a sexual act. She is shown full frontal, grimacing or screaming, her baby’s head peeping cheekily out from the vulva, while she clutches herself in a terror that could also be ecstasy.’

Despite her prolific output, Barbara felt fame was eluding her; she remained tormented by personal as well as literary insecurities. These were not helped by the many pilgrimages she and Jo made around the world to sites of significance to her heroes: following, for example, in Faulkner’s steps and making the pilgrimage to Lawrence’s memorial in Taos, New Mexico.

When she was diagnosed with cancer in 1984, Barbara accelerated her writing and printmaking, producing another seven books, including her final masterpiece, the ‘joyfully comic and satirical’ Good Night, Mr Moon (1992). Undaunted in spirit, she died in December 1991 after a Frida Kahlo-like struggle with illness and pain.

In her last years Jo was saintly in his devotion, nursing her and even helping her to make prints when she could no longer stand. He meditated with her for hours each day. They both came to anticipate her death as ‘a quiet, dignified movement from one state of being to another more spiritual one’.

Barbara’s spirit certainly informs this long-awaited and rewarding biography, which I hope will win a new generation of readers to her disturbing and truly visionary novels.

Comments powered by CComment