- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dowling revisited

- Article Subtitle: Reversing the neglect of settler art history

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The settler art history of Australia is not a long one – not much more than two hundred years – so it is all the more surprising that the literature of its first century should remain so riddled with holes. It is a sad reflection on the priorities of the academic and curatorial professions that (certainly as far as concerns that conventional, fundamental professional resource, the monographic study) some very significant artists have been neglected or completely ignored. To give just a few examples, it is years since there was anything new or substantial on Augustus Earle, S.T. Gill, Nicholas Chevalier or Louis Buvelot, while there have never been focused, extended studies of first-generation early colonial artists such as the surveyor-explorer G.W. Evans and the natural history painter John Lewin, of Benjamin Duterrau, artist of The Conciliation (1840), Australia’s first history painting, or of the 1860s and 1870s landscapists J.H. Carse, Thomas Clark and Henry Gritten.

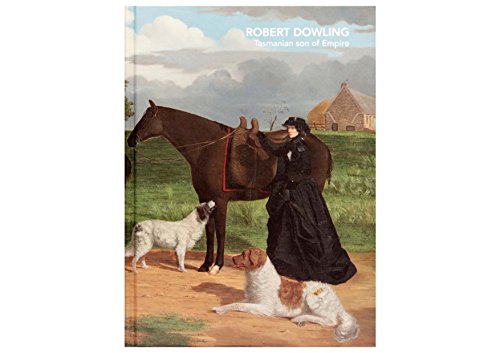

- Book 1 Title: Robert Dowling

- Book 1 Subtitle: Tasmanian Son of Empire

- Book 1 Biblio: National Gallery of Australia, $49.95 hb, 192 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Happily, however, there are still a few labourers toiling in the vineyard of nineteenth-century art, with the expertise and the passion to fill such gaps. The late Joan Kerr’s magisterial Dictionary of Australian Artists (1992) did much to extend our basic knowledge of ‘painters, sketchers, photographers and engravers to 1870’. Since then we have seen such useful and often revelatory exhibitions and publications as Elizabeth Ellis’s on Conrad Martens, Christa Johannes’s on W.C. Piguenit, John McPhee’s on Joseph Lycett, and the present writer’s on John Glover. The latest addition to the updated canon is the Anglo-Australian Robert Dowling, finally given his due in this exhibition and book from the National Gallery of Australia. Curator and art historian John Jones has been ‘the Dowling guy’ for a long time (he began his research on the artist for a Master’s degree some thirty years ago), but it is evidently the enthusiasm of NGA Director Ron Radford that has ensured the resurrection of Jones’s research and its presentation in this long-overdue survey. They both deserve our warmest thanks.

Dowling was perhaps not a great painter, nor even a consistently good one, but he certainly had some stellar moments. Moreover, the story of his life and work is deeply interesting both in its own right and in terms of art and social histories, and has strong resonances for the twenty-first century reader and viewer. Born in Colchester in 1827, he migrated to Van Diemen’s Land with his family at the age of seven; his father was Reverend Henry Dowling, the colony’s first Baptist minister. Apprenticed as a saddler for seven years but largely self-taught as a painter, he nevertheless soon abandoned awl and needle in favour of maul-stick and pencil, first advertising himself as an artist in 1850. His portraits of family, friends and colonial patrons from the early 1850s are distinguished by a sharp eye and a deft touch in capturing facial likeness, though he was less adept at anatomy: in almost all of his figures from this period the heads are unconvincingly stuck on top of rather too small bodies and rather boneless (or else discreetly hidden) hands. After the remarkable (but little known – another one!) Henry Mundy and the prolific Thomas Bock, Dowling and Knut Bull are probably the best of Tasmania’s portraitists in oil from that golden age just before the daguerreotype.

Moving across Bass Strait at the end of 1854, Dowling continued to work as a portrait painter, now with Port Phillip District squatters (the well-acred Ware family were his in-laws) as his subjects. From this period also come what for contemporary viewers are probably his most remarkable and appealing pictures: a series of family groups in which indigenous and settler Australians are shown in harmonious coexistence, even amity: works such as Mrs Adolphus Sceales with Black Jimmie on Merrang Station (c.1855–56, National Gallery of Australia) and Masters George, William and Miss Harriet Ware with the Aborigine Jamie Ware (1856, National Gallery of Victoria).

Returning to Tasmania, Dowling gathered support from a public subscription and in 1857 sailed for England, where he was to spend the next two and a half decades, ‘the local colonial boy who … made good at “Home”’. Dowling is in fact the earliest exemplar of the Cultural Cringe and the Provincialism Problem, the first of that long line of Australian artistic expats that runs from Arthur Streeton and Rupert Bunny to Arthur Boyd and Sidney Nolan to Ricky Swallow and David Noonan. Improving his dodgy anatomical drawing through life classes at Leigh’s Academy, Dowling soon established himself in London: initially with colonial exotica such as Aborigines of Tasmania (1859, Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston) and the autobiographical Early Effort – Art in Australia (1860, NGV); later (not surprisingly, given his family background) with moralising genre and biblical subjects; and finally (following two visits to the Middle East in the 1870s) with more generic Orientalist scenes. Regularly shown at the Royal Academy from 1859, Dowling’s success in Britain greatly enhanced his reputation in Australia. He continued to send pictures back to the colonies for exhibition and sale, most via his brother and indefatigable supporter Henry.

The fourth and final chapter of Dowling’s professional life was his return to Victoria in 1884, where, thanks both to those long-sustained relations with Western District pastoralist patrons and to a fortuitous absence of competitive talent, he became for a couple of years Melbourne’s most prominent portrait painter, producing the quite lovely Miss Robertson of Colac (1885–86, NGA), as well as sober and competent if unremarkable portraits of ‘some eighteen prominent figures from Church, State, Law and Academe, between April 1884 and … April 1886’. That month he returned to England, where he died suddenly of a heart attack in July.

Jones describes this life and professional achievement in a text which is both comprehensive and precise. There has been some fine art-historical detective work, most notably in the reattribution of Breakfasting Out (1867, Museum of London), the first picture Dowling showed at the Academy (but thanks to a false signature long ascribed to the British painter Charles Hunt and dated 1881) and of the spooky Daniel in the Lions’ Den (1882, Philadelphia Museum of Art), formerly given to Gustave Doré, as well as in the retitling as Sabbath in the Country of the work from the Joseph Brown collection, formerly known as An Afternoon Siesta (1859, private collection).

I would take issue with Jones on a couple of points of interpretation. The relative ‘blandness’ of Knut Bull is a somewhat unfair dismissal, though admittedly we have not yet had the Bull exhibition and book to permit a proper comparison of the two artists. The Baptism of Christ (1863, QVMAG) is certainly a compelling picture: both in its central motif and in its combination of banality and hysteria, the work weirdly prefigures Bill Viola’s video Ocean without a shore (2007, NGV). But to describe it as ‘the most astonishing religious image in Australian art’ is something of an overstatement. This assessment devalues Dowling’s own achievement in the dramatic Daniel, not to mention Alexander Schramm’s beautiful Biedermeier Madonna of 1851 (Art Gallery of South Australia), the work of Christian modernists such as Justin O’Brien and Leonard French, and for that matter any number of late twentieth-century Aboriginal painters. And while I do not know the history of the Adye Douglas family miniatures (details of provenance are not included in the book’s catalogue listing), I do have serious stylistic reservations about their attribution to Dowling.

But if I have any substantive complaint, it is only that I wanted more. Jones attempts to pack a considerable amount of biographical, historical and curatorial material into a singular narrative and within a small space. As a result, the text is occasionally rather clotted with the names of sitters, patrons and works, which, particularly for readers unfamiliar with colonial art and society, can be confusing. More disappointing is the fact that the archival-antiquarian focus on the who, what, when and where of the pictures entails a corollary neglect of analysis and interpretation. That Jones is well up to this kind of writing is illustrated by his fine chapter on the Aboriginal subjects, which provides rich historical and anthropological context, and some sensitive reading of individual works. A similarly extended introduction to the social function and artistic achievement of portrait painting both in colonial Van Diemen’s Land and Victoria and in metropolitan London would have helped the reader to understand more clearly the artistic and economic successes and failures of Dowling’s primary practice. Likewise, while Jones introduces Dowling’s 1870s visits to Egypt and Palestine with a brisk and cogent definition of Orientalism, it would have been instructive to have provided more than a mere paragraph or two. The European and specifically British context of this imperial aesthetic is broad and rich, as was shown in the recent exhibition The Lure of the East (Tate Britain, 2008), and the relationship of Dowling’s work to that of artists such as Thomas Seddon and William Holman Hunt, and more especially of John Frederick Lewis, could have been fruitfully explored. Reproduction of the ‘expensive, elaborate, Egyptianesque frame’ on A sheikh and his son entering Cairo, on their return from a pilgrimage to Mecca (1874) would also have been nice.

More generally, I would like to have seen reproductions of more comparative material, both by the artist himself (the fascinating Duet – Mary Queen of Scots and Rizzio [c.1860–65], with its probable self-portrait in Elizabethan drag, and the oil version of Moses viewing the Promised Land from Mount Nebo, 1879) and by his contemporaries both in Australia (Bull, Bock, Mundy) and the United Kingdom (Millais and Lewis). Richard Nicholas’s 1880s copy of Tasmanian Aborigines (NGV) sounds utterly intriguing, but it remains a textual ghost only. While on the matter of reproductions, it must be observed that not only is the colour rather dry and chalky, but also the combination of the volume’s bijou scale and many paintings’ landscape format means that the larger plates have an unfortunate gutter line, a problem that might have been overcome with a few judicious gatefolds.

In closing, I must also point out a handful of errors that seem to have eluded the editors, but only because reviewers’ pedantic identification of footnote flaws is as much of a professional convention as is the monograph itself. Firstly, as any contemporary Aboriginal Tasmanian will tell you (and in no uncertain terms), the abuses visited upon their ancestors did not constitute a ‘genocide’ – the Palawa are still very much a living community; I do not think that Jeremiah George Ware – businessman, pastoralist, horseman, cattle breeder, a member of parliament and of the Hampden Roads Board – deserves the disparaging adjective ‘feckless’; Dame Laura Knight (1877–1970) cannot have attended Leigh’s Academy before 1860; and the disapproving woman with the basket on her head in Breakfasting Out (1859) is a seller of watercress, not of flowers.

However, the fact that I can be so very particular in my criticisms is testimony to the author’s overall exemplary scholarly standards, and to the serious interest and importance of this book and exhibition. Ron Radford is occasionally prone to hyperbole, but in this instance he is right on the money when he states in his introduction that Dowling ‘is here fully established as Australia’s most important portrait and figure painter of the late colonial period’.

Comments powered by CComment