- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Radical love

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Witnesses as diverse as Plato in the Republic, James Joyce in Ulysses and Lewis Mumford in The City in History have testified that ultimately, in some metaphorical if not metaphysical sense, the City is, above all else, an expression of love. Terry Irving and Rowan Cahill, luminaries of the New Left in the 1960s and 1970s, currently associated with the University of Wollongong, are assuredly in love with Radical Sydney, a city which may or may not be with us still. There is, however, a whiff of Yeats’s ‘Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone, it’s with O’Leary in the grave’, as there is of Beckett’s borrowing from the French: ‘The only true Paradises are lost Paradises’. Yet Irving and Cahill are anything but Romantics. Radical Realists, rather. They are not afraid to quote those who disagree with them: for example, the head of the Australian Bureau of Crime Intelligence who described the Sydney of the 1950s as ‘a stinking city, one of the most corrupt in the world’. Indeed, as the soundtrack of Underbelly insists: ‘It’s a jungle out there.’

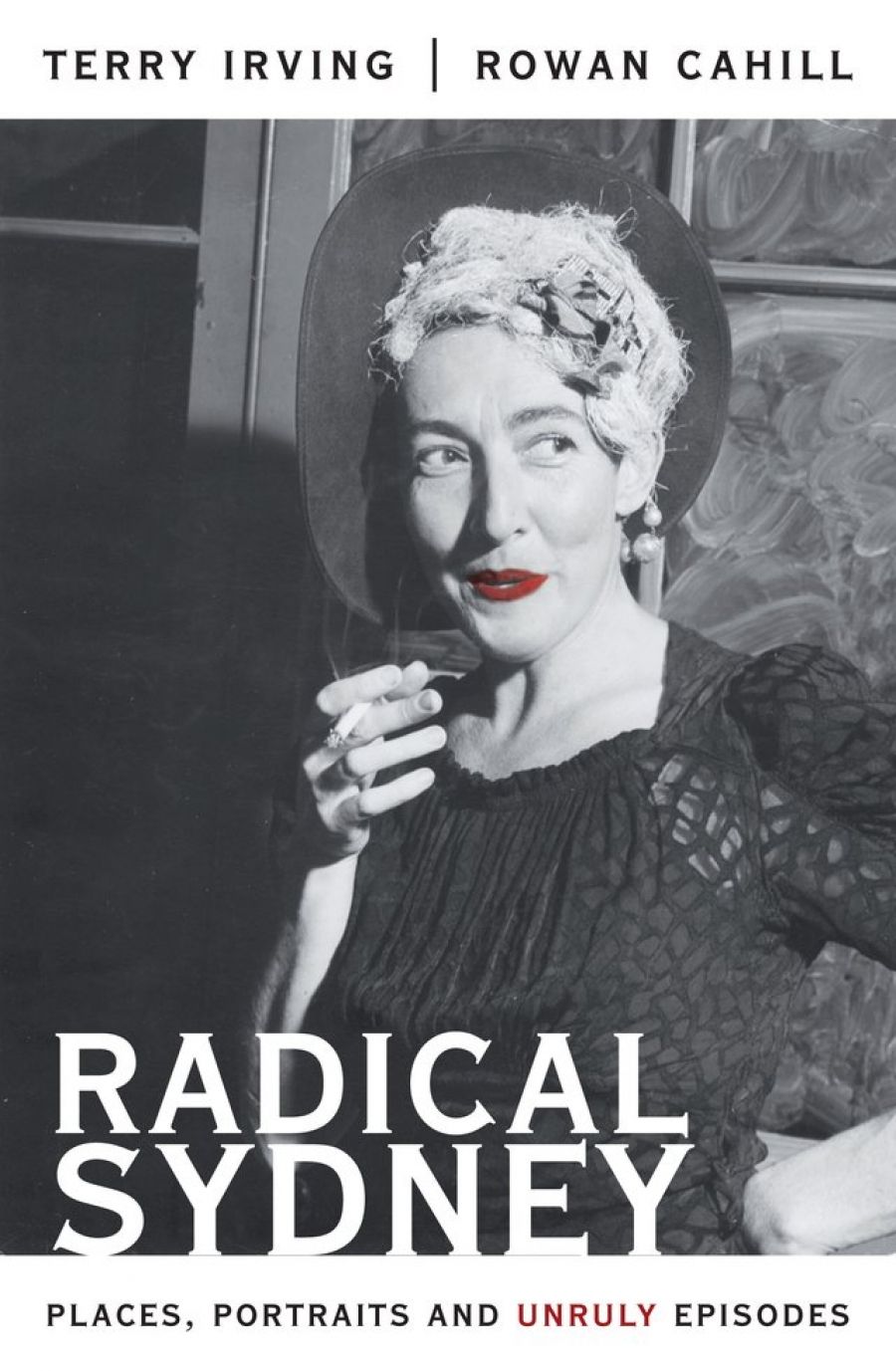

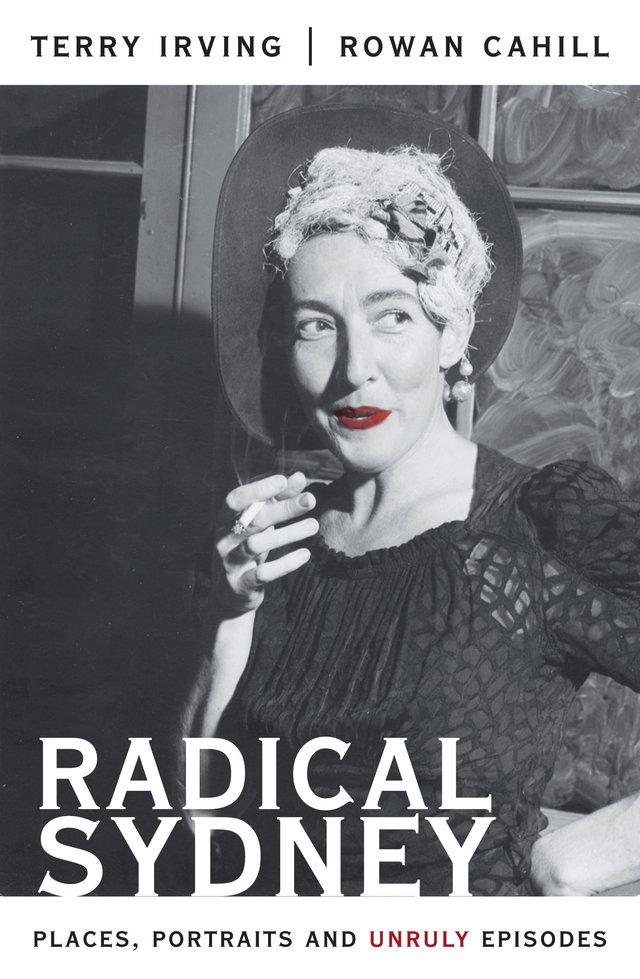

- Book 1 Title: Radical Sydney

- Book 1 Subtitle: Places, Portraits, and Unruly Episodes

- Book 1 Biblio: UNSW Press, $39.95 pb, 368 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

To this end, it is richly studded with photographs and maps, both past and present. It comprises almost fifty bite-sized chapters, starting at Observatory Hill on Dawes Point in the late eighteenth century and concluding nearby in the Hungry Mile at the Rocks, scene of thuggish Howard government action using balaclava-clad security forces and fierce dogs to suppress union activity. In between we encounter, for example: ‘The 8-hour day and the Holy Spirit – Garrison and Mariners’ churches, The Rocks’; ‘The Henry Lawson Statue: Iconic Henry and “faded” Louisa’ (the Domain); ‘Margaret Street Riot, 1947’; ‘Dorothy Hewett and the Redfern Reds – Lawson Square’; ‘The Siege of Victoria Street – Kings Cross’; ‘Combating the “greatest social menace” – Darlinghurst Police Station’; ‘Survival Day, 26 January 1988, Koori Redfern – The Empress Hotel, Regent Street’.

As the chapter titles suggest, this book will not be warmly welcomed by the conservative commentators of the centre pages of the Sydney Morning Herald – atrabilious Miranda or grumpy Gerard – or of The Australian, passim. This is all the more reason to welcome it here. We used foolishly to believe that Australia was a ‘classless society’. Far from it, as this book amply substantiates. There has long been a war between the North Shore/Eastern Suburbs and the inner-city and inner-Western suburbs, as there has between the police and a radical citizenry. Australia, Irving and Cahill point out, is not usually thought of as a country marked by civil violence: ‘But as the story of the New Guard shows, Sydney came perilously close to an armed uprising to overthrow liberal democracy in the country’s most populous state in 1932, and the danger came from the men of property, not the “Reds”.’

One of the aims of this book would thus seem to be to correct the biases of Tory history, and a worthy aim it is, but at times the corrections would appear to have been made by others. To claim that The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature ignores the young Henry Lawson’s ‘radically republican and socialist’ politics, as well as ignoring his mother Bertha, ‘long absent from the public record and largely remembered simply because she was Henry’s mother’, may be true, but it fails to note that corrections set in with Brian Matthews’s Louisa (1987). One can sympathise with Radical Sydney’s having undergone a ‘long gestation’, but Matthews’s study received a wide and richly deserved press.

Radical Sydney strives to speak for the dispossessed, and who more dispossessed of Eden (as William Faulkner wrote of another enclave) than indigenous Australians? The book rightly reminds us of Paul Keating’s 1992 Redfern speech. He called for an act of recognition by Australians of European descent: ‘Recognition that it was we who did the dispossessing. We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought the diseases. The alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. We practised discrimination and exclusion.’

We know all too well what Keating’s successor and his ministers did with those noble sentiments. (And here is a curiosity of juxtaposition. The page that carries Keating’s speech carries a photograph of the young Dorothy Hewett, Redfern resident, taken in 1959 for the publication of her great working-class novel Bobbin Up [1959]. Is it just my fancy, or does Dorothy look for all the world like Keating in a blonde wig?) But the authors, social historians rather than fantasists both, know that ‘noble sentiments’ are not enough.

Today, radical Redfern is disappearing. Gentrified terraces, upmarket dwellings and corporate offices advance over the suburb, dispersing its recalcitrant and sporadically mutinous white and black citizens. This process looks inevitable, but is in fact the result of political decisions. … Our rulers, having decided that Sydney must be one of the ‘global’ cities of finance capitalism, encourage the spread of concrete and glass but ignore its consequences for the city’s heritage.

Go look at the Hungry Mile. It’s QED writ large.

Comments powered by CComment