- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Vodka fumes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Lily Bragge, performer and arts writer, has had what you might call a dramatic life, the sort that makes people say, ‘You should write a book’. It involves almost every kind of catastrophe that may befall a young woman in suburban Australia: sexual abuse, parental violence, emotional instability, depression, drug addiction, ill-fated romances, unexpected pregnancy, cancer, bereavement, domestic violence, loss of custody, suicide attempts, a great deal of partying and … well, you get the idea. In My Dirty Shiny Life, her first book, Bragge tells in braggadocio style the troubling and fulsome tale of a life lived far beyond the limits of ordinary endurance, one that makes for a riveting but disorienting read.

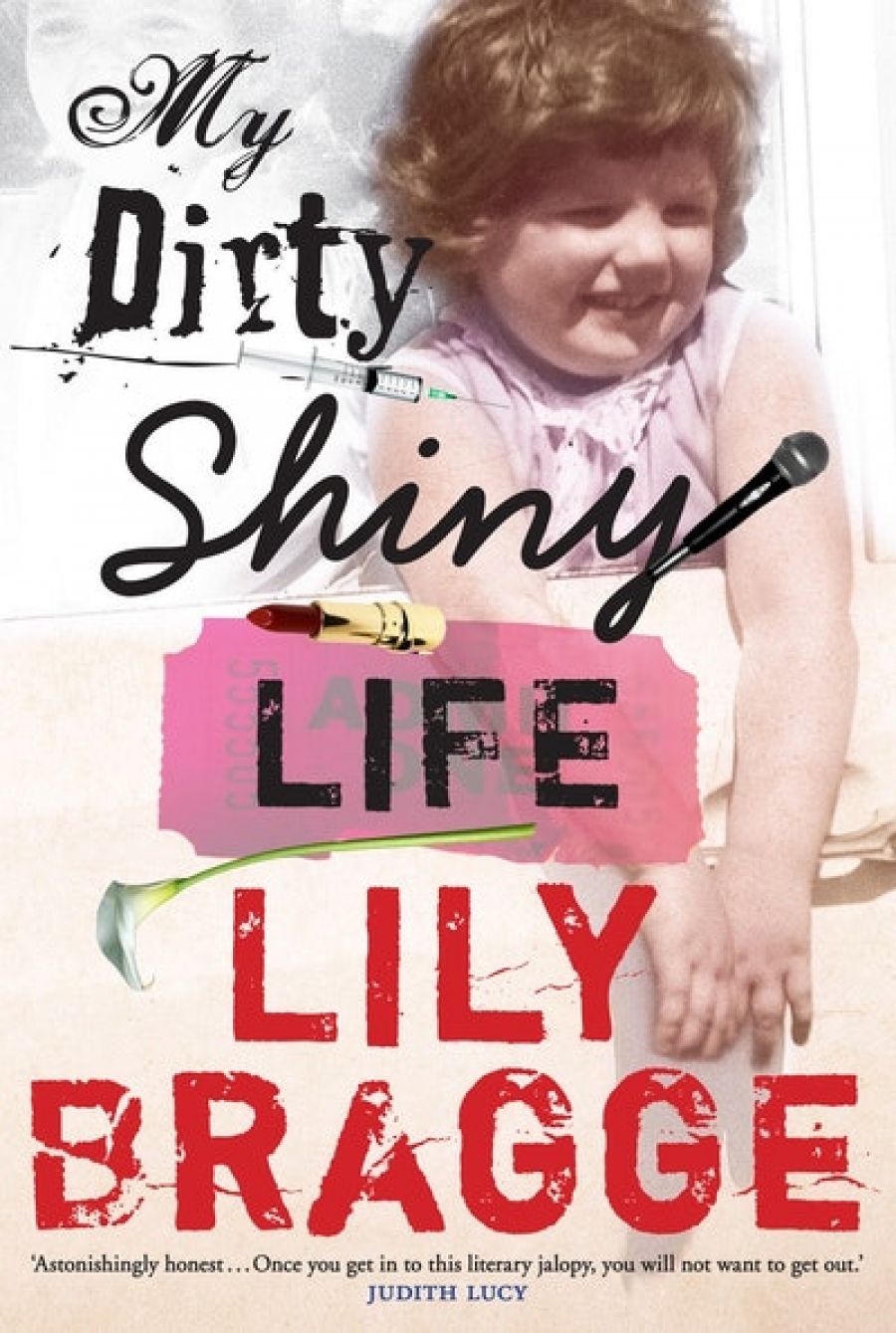

- Book 1 Title: My Dirty Shiny Life

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $32.95 pb, 258 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

As with most memoirs, it raises some questions: how do the components of this genre – voice, style and story – fuse? Is the reader listening to a story told in a bar, looking for writing that transports, or making a friend? Should a memoirist simply relate the anecdotes of her life, or synthesise them into a greater theme? Is it enough to believe that an interesting life makes an interesting book?

Born to a middle-class, naïve mother and a no-good trucker/musician ‘sociopath’ of a father, the young Lily grows up with her siblings in the suburbs of Melbourne and in small rural towns (‘Life Rule 8: Beware of any town anywhere that has a name beginning with the letter W’). Uncle Bob molests her. Dad terrorises her. Dad threatens Mum with a gun. Dad sends birthday cards that make her glow. Lily steals coins and sings songs and grows up to be a delinquent. Bragge describes her childhood with an enterprising eye for detail (the ‘six bright orange and gold vinyl chairs with a large brown laminex table’ of her father’s house). At times she breaks into italicised present-tense revisitings of her younger self.

For me this was a trying beginning to the book, despite its drama and its frequent humour. As with many childhood reminiscences, we receive a series of anecdotes – not quite vignettes – that promise import but add only information. Here, memoirists meet a crucial leveraging of a book’s economy: do you infuse recollections with retrospective analysis or simply present the material, fragmented and banal though it may read? Every scrap contributes, of course, but a constant stream of small incidents, some no more remarkable than those of any child, runs the risk that the reader will question the author’s grasp of her subject.

The story settles into an easier, if cacaphonic, rhythm in Bragge’s adulthood. Unsurprisingly, she has a tempestuous adolescence and carries that tempo into sex, share houses, early work as a stand-up comedian and what becomes a pattern of losing control. Depression fells her; self-medication deranges and heartbreak tempers her. She has a child whom she loves fiercely, but in one strange incident Bragge tempts him with champagne. She blunders through to her thirties – loud, large, one might even say ‘blowsy’ – despite her self-doubts, and gradually becomes a heroin addict. For me, also an ex-addict, this was a difficult passage to read (not least because she mentions my own former drug dealer). The writing screams with rage both at herself and at the treatment she was offered. It is heartbreaking, at this point in the story, to see this vivid, indomitable, formidable woman confess her ultimate weakness. Throughout My Dirty Shiny Life, Bragge makes no bones about her human frailty, and relates her foibles with admirable candour and lack of sentiment – even relish – but the heroin era exposes the fragile bravado that she offers elsewhere.

A suicide attempt sees her being sectioned, then she cleans up from addiction in an oddly elided caesura, and vows to reform. But the opera continues: romance is both consolation and grief; the booze still beckons; a surprising epiphany closes the story. Now in her forties, Bragge works as an arts reviewer. Presumably, the writing of this book comes from a more settled place, a vantage of distance. It is to her credit that she remembers, never mind manages to narrate, a life lived so extravagantly.

I ended up cherishing Bragge and her story, swept along by the tumult of her life and the courage with which she lays it bleeding and heaving before us: not an easy thing to do. A point of irritation, however, was her tone, quite different from that of her journalism. The book is told almost as if by someone breathing vodka fumes over a bar counter, full of cutesy terms, chatty asides and warm addresses to the reader, ‘my friend’. Bragge emphasises drolly at the beginning of the book that she is ‘likeable’, and indeed she is, through all her appalling vicissitudes, but she works a little too hard in hoping to remain so. Other readers, for example fans of Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love (2006), may enjoy the complicit voice.

Bragge’s book reflects the haphazardry of her extraordinary life: at times I wondered what was the point. But to read a memoir is to enter another person’s life, on her terms, not yours, and Lily Bragge, in the opera of her experience, gives us a rattling good performance of almost every emotion under the sun, even with a twist at the end.

Comments powered by CComment