- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘My problem is that because of my anxiety disorder, publicity is close to torture,’ Austrian novelist Elfriede Jelinek tells Ben Naparstek, explaining why she informed a newspaper in 2004 that she hoped she wouldn’t be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature (she was). With or without anxiety disorders, writers face a conundrum. They communicate through the written word, but increasingly they also talk aloud in public and in the media. When writers are interviewed, they often traverse an awkward middle ground between adopting a public persona and revealing the inner sources of their inspiration. There is a tension – frequently evident in the pages of In Conversation – between a writer’s need to publicise, explain or defend his or her works and beliefs, and a desire to allow the writing to speak for itself. For many writers, there is also the challenge of making their verbal communication as erudite as their writing. As Norwegian novelist Per Petterson tells Naparstek, ‘Talk is entirely overvalued, I think.’

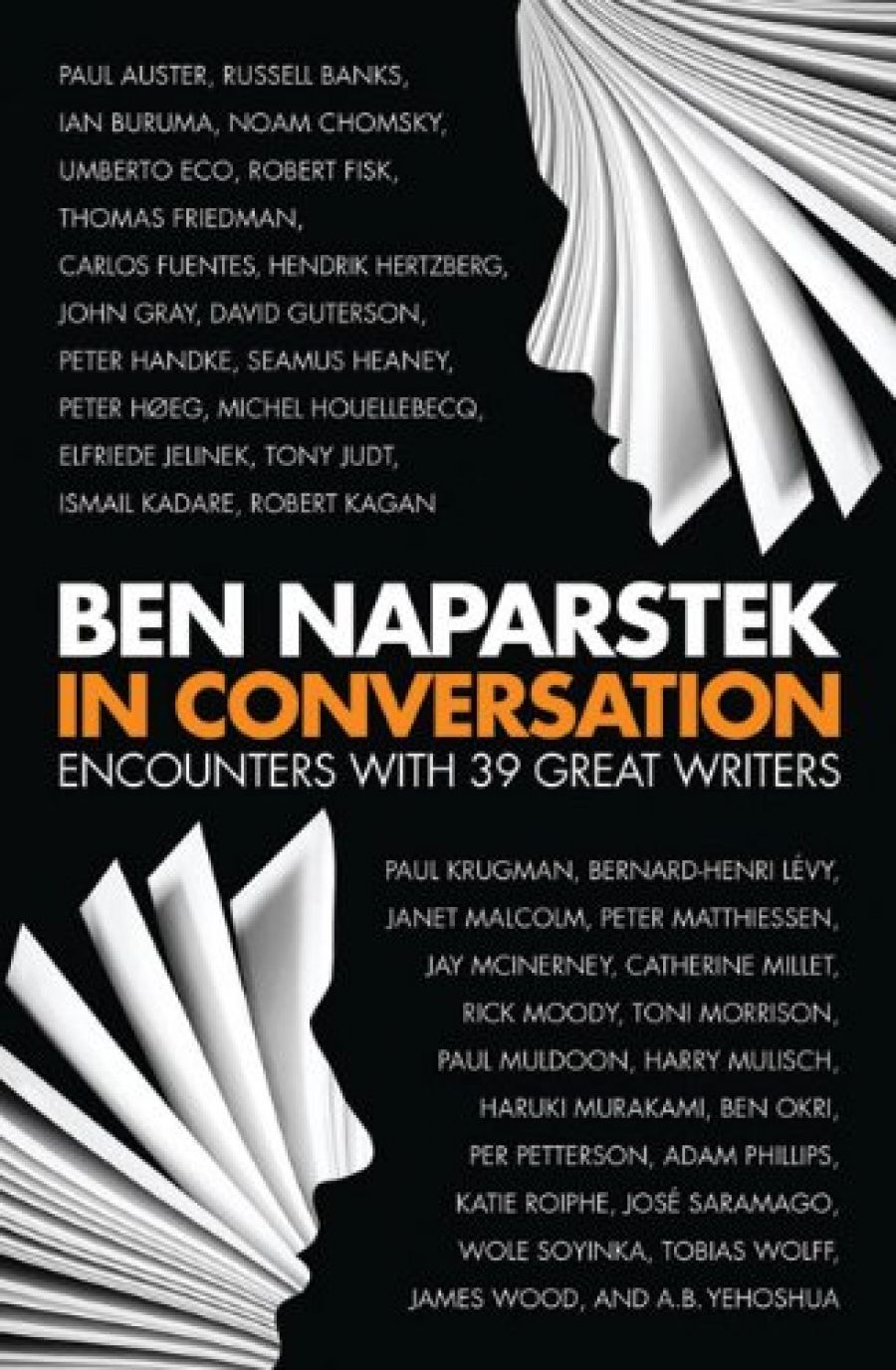

- Book 1 Title: In Conversation

- Book 1 Subtitle: Encounters with 39 great writers

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe Publishing, $32.95, 272 pp

In a short preface, Naparstek argues that interviewers ‘will inevitably have their own agenda and will construct a narrative at odds with the subject’s fuller conception of herself ’. This shows self-awareness, for what follows are not straight interviews transported onto the page but short, sharp, carefully crafted profiles. In other words, they are Naparstek’s interpretations of the lives and works of various writers. They are, as Naparstek happily concedes, ‘very partial constructions of lives based on brief encounters’, not least because many of the profiles focus on a particular book the author is promoting.

The writers included are a reasonably diverse bunch, although there is a male skew (and, incidentally, no Australians). Among a roughly equal number of fiction and non-fiction writers – some are both – are heavyweights such as Toni Morrison, José Saramago and Umberto Eco. Still, it requires a slightly generous definition of ‘great’ to justify the subtitle’s reference to ‘39 great writers’. An example: Noam Chomsky might be an influential left-wing agitator and a world-renowned linguist, but his prose style can be ponderous and repetitive, as if he wants to bore his readers into becoming activists.

Throughout, Naparstek’s prose is crisp, relaxed and unflashily learned. It is at its best and most enthusiastic when he is talking politics. He can be blunt: Michel Houellebecq’s ‘aggressive smoking habit and alcoholism suggest that his jaundiced vision may have less to do with the times than with the depressive lens through which he views them’. Mostly, Naparstek airs his own views and agendas without imagining that he is more important than his subject, but occasionally he herds interviewees’ answers into enclosures of his own making. For example, he is dismissive of prominent US neo-conservative Robert Kagan in a way that renders near-redundant Kagan’s contribution.

Occasionally, too, Naparstek displays a journalistic irritation with interviewees who decline to answer certain questions: Ben Okri ‘refuses’ to discuss his wartime experiences; John Gray ‘refuses’ to talk about his upbringing or personal life. Still, Naparstek’s probing of the personal sometimes elicits fasci-nating responses, including Chomsky’s lament about his daughter’s decision to live in poverty in Nicaragua: ‘Our lives are remarkably privileged by world standards, but we don’t help anyone if we give them up ... I’d be happier if she had running water in her house instead of a cold trickle a couple of hours a night, but that’s her choice.’

Although there are no duds, some profiles have more appeal than others. It is more interesting, for example, to hear Jelinek say, ‘I have had the strange fate of having two crazy parents, but seeing as the whole world is crazy, maybe this is normal!’ than to hear Paul Auster comment, ‘A few more years went by, and the idea of filming it just kept coming back to me.’ Two pro- files stand out. Naparstek’s encounter with the Austrian novelist Peter Handke, an apologist for Slobodan Milošević, is riveting, disturbing and nuanced. The profile of Israeli novelist A.B. Yehoshua is a potent examination of the politics of politically charged literature, especially when Naparstek contrasts Yehoshua’s views with those of two of his critics, fellow Israeli writers Yitzhak Laor and Etgar Keret.

At times, the brevity of the pieces requires a sacrifice in terms of depth. Naparstek tells us that US political commentator Hendrik Hertzberg commences a ten-minute rant on electoral reform before cheerfully admitting, ‘There’s an unspoken quota of how much I can flog this type of analysis.’ But what’s missing is the rant itself, which promises to represent Hertz-berg at his most enlivened – even if, as Naparstek says, it is ‘as intricate and winding as a Californian gerrymander’. Similarly, Naparstek asks Morrison if she regrets once calling Bill Clinton America’s first black president. She replies, ‘I didn’t even say that ... I said he was treated like one – that is, with complete disrespect, complete, “You’re guilty already.”’ Naparstek tells readers ‘for the record’ that Morrison did write it, but he does not reveal if he told Morrison this or how she responded.

Mostly, though, the profiles shine in abbreviated form. In combination, they hold together like a sort of mosaic, their brevity and variety somehow giving the book an unexpected cohesiveness. As such, it is more rewarding to read In Conversation from start to finish than to approach it like a lucky-dip. Naparstek’s profiles succeed on two levels: they invite readers to seek out new writers, and they are stimulating entertainment.

Comments powered by CComment