- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Academic historians only took to urban history in any systematic way during the 1970s, but Melbourne, regardless of what historians might have had to say about it, has always had a strong sense of its own identity and culture. In the heyday of 1880s ‘Marvellous Melbourne’, journalist Richard Twopeny saw the city as representing ‘the fullest development of Australian civilisation, whether in commerce or education, in wealth or intellect, in manners and customs – in short, in every department of life’. English historian J.A. Froude, staying in style as a guest at Government House, saw Melbourne people as having ‘boundless wealth, and as bound-less ambition and self-confidence’; they were ‘proud of themselves and of what they have done’.

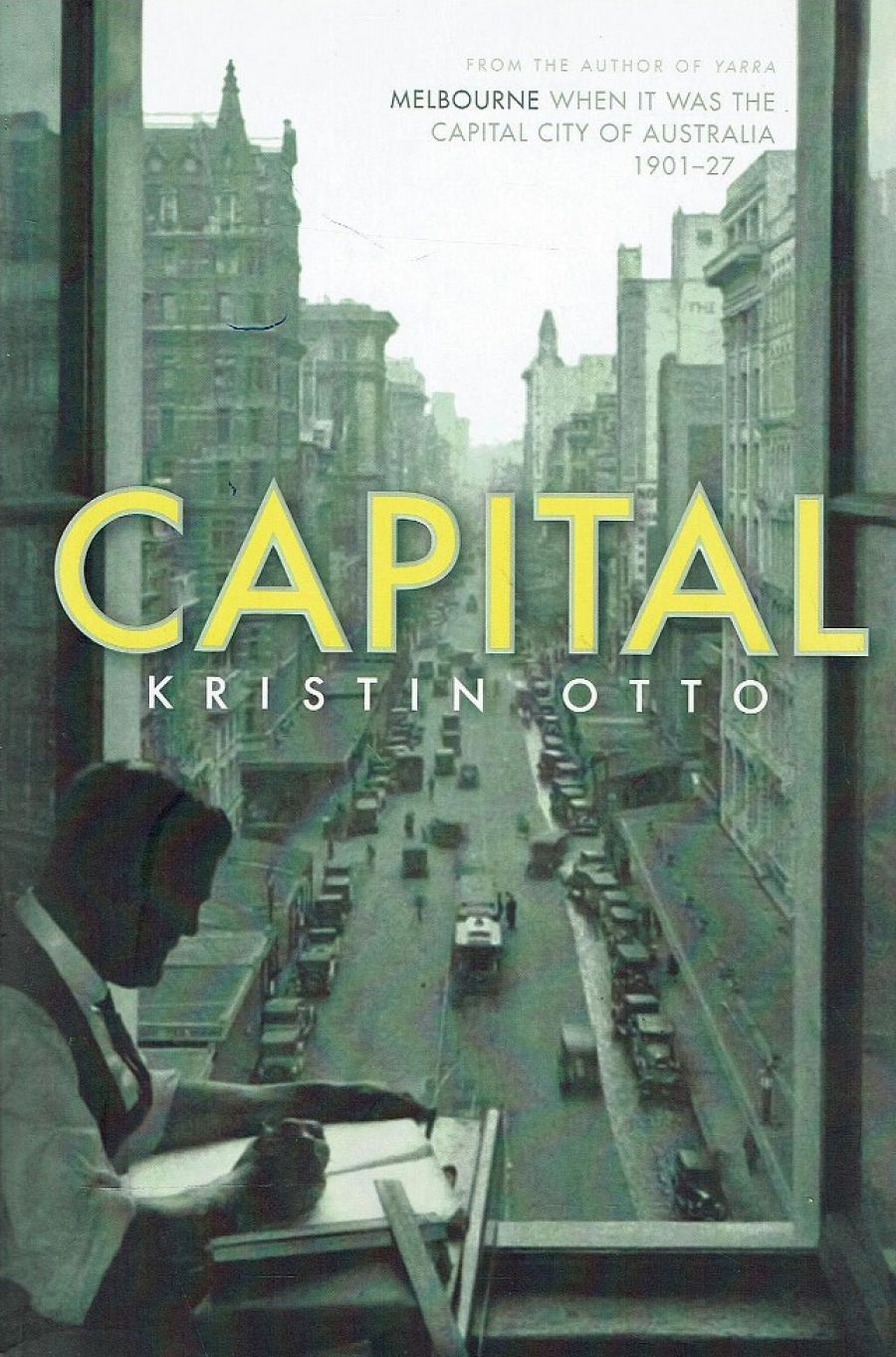

- Book 1 Title: Capital

- Book 1 Subtitle: Melbourne when it was the capital city of Australia 1901–1927

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $39.95 pb, 388 pp

When, with the achievement of Federation in 1901, Melbourne became, for a time (which turned out to be more than twenty-six years), the national capital, this might have seemed an appropriate apotheosis for the still-young metropolis, but the heady optimism of ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ had evaporated with the Depression and financial collapse of the 1890s. Federation was more in the way of an economic and psychological restorative, and some compensation for Melbourne’s having ceded its status as Australia’s largest city back to Sydney. Reading Kristin Otto’s Capital, you would not be aware of any of this prehistory. The introduction offers no more than some suggestive definitions of the word ‘capital’, and with that the reader is plunged into a chapter of ‘Celebrations’ and the kaleidoscopic journey to 1927 is underway.

It is soon clear that this is not a conventional history. If it is to be considered a slice of urban biography, as the term is sometimes applied now, it is only so in a particular and limited sense. ‘If we define the social capital of a city as its people, and the working capital of its people as their ideas,’ Otto writes, ‘then Melbourne was a small town where extraordinary people did amazing things.’ Melbourne’s status as the temporary capital of the infant nation provides a loose – very loose, in fact – framework for the story, but the focus is really on that other form of capital, the extraordinary people doing amazing things.

Capital assembles an interesting cast. A few prime ministers, most notably Alfred Deakin and Billy Hughes, make their presence felt; what might be described as a hustle of entrepreneurs includes Helena Rubinstein, H.V. McKay, ‘Mac’ Robertson, George Nicholas, Sidney Myer, Keith Murdoch and John Wren. Apart from Mrs Aeneas Gunn and C.J. Dennis, writers hardly get a word in, but a few painters, such as Ellis Rowan, Tom Roberts and Violet Teague, get a guernsey; while the imposing Janet, Lady Clarke, the widow of Sir William, represents Society with a capital S, as well as that bulwark of conservative womanhood, the Australian Women’s National League. If there are two leading players in this cast they are Nellie Melba and John Monash – Melba who, in her identification with the city of her birth, promoted herself as its patron saint enthroned at Coombe Cottage, while Monash, ‘soldier, engineer and administrator’, as the Australian Dictionary of Biography classifies him, seemed to have a hand in everything. Melba and Monash both died in 1931; their funerals were huge public affairs.

Otto also picks out a number of buildings or sites as somehow symbolic in their Melbourneness: the Exhibition Building, of course, where the duke of Cornwall and York opened the first federal parliament; the Observatory, where Guido Barachi doubled up as astronomer and weather forecaster; the marvellous, eccentric Cole’s Book Arcade; the spectacular domed reading room of the Public Library; Walter Burley Griffin’s stylish Café Australia, as well as his unique Capitol Theatre, with its magically lit ceiling; and, tucked away in the hills, St Peter’s Memorial Church, Kinglake, for which Violet Teague, in the wake of the War, painted an altarpiece. (The church was destroyed on Black Saturday, but Teague’s altarpiece had much earlier been moved to St Paul’s Cathedral and replaced with a copy.) In the concluding chapter, for some reason titled ‘Style’, the electrification of Melbourne’s railways triggers an enjoyable exploration of the massive Flinders Street Station, with its signature meeting place, ‘under the clocks’.

Otto takes particular pleasure in mapping the connections between the different members of her cast. McKay, who had long had his eye on the Clarkes’ country house, Rupertswood, finally got his hands on it in 1920. Robertson’s ‘Electric Fairy Floss Candy Spinner’ featured at Luna Park, opened in 1912; Monash was chairman of Luna Park Ltd. Melba ‘always popped in for a facial’ at Helena Rubinstein’s salon. More tenuously, when E.W. Cole of the Book Arcade advertised for a wife, the Miss Eliza Jordan who answered, and did go on to marry him, happened to be ‘the paid companion to Janet Clarke’s mother-in-law’.

One cannot help noticing, however, the ‘extraordinary people’ missing from Otto’s collection. Conductor and com-poser Marshall Hall, who did so much to enliven Melbourne’s musical scene, but upset the wowsers with his bohemianism, would have been a gift for Otto, particularly as he had such a close relationship with both Deakin and Tom Roberts. Deakin’s daughter Ivy played in his orchestra; she and her husband, Herbert Brookes, a prominent business-man and community leader, hosted the literary and musical T.E. Browne Society. And what about the poet and literary figure Bernard O’Dowd, whose much-quoted sonnet ‘Australia’ greeted the coming Commonwealth in 1900? Theatre is noticeably absent: ‘Australia’s sweetheart’ Nellie Stewart, still a favourite in the early 1900s, would have been a welcome addition, or Allan Wilkie, who promoted his Shakespeare company as an embryonic national theatre and won the support of Prime Minister S.M. Bruce.

So, too, one might wonder why the 1923 police strike receives such full treatment while the politically and industrially more significant railway strike of 1903 is ignored. The narrative doffs its cap to prime ministers, but state politics is totally absent. Perhaps most remarkably, Melbourne’s ‘national game’ (as Streeton dubbed it in a painting), Australian Rules football, only sneaks in on what is virtually the last page in the noble form of Doug Nicholls arriving in Melbourne and, because of his skin colour, having trouble getting a game.

Capital is one of those books that doesn’t end; it simply stops, rather as if the author has run out of puff. In a single sentence we are told that in May 1927 the federal government and parliament left Melbourne for ‘a new purpose-built capital’. The name ‘Canberra’ is not even uttered. Surprisingly, the visit of the duke and duchess of York to Melbourne which preceded the move is not covered, though it would have made a neat bookend, with the duke’s father having opened federal parliament in 1901.

Otto might well have seized upon the terrible air crash that cast a blight on the royal couple’s arrival in Melbourne, when two RAAF planes that were part of the welcoming fly-past collided near Government House. And wouldn’t the unstoppable Melba singing the national anthem at the opening of Canberra have provided an appropriate postscript? One could go on, but as an entertaining romp through early twentieth-century Melbourne, Capital will probably find willing readers. It is written in a breezy, offhand style, and the text is peppered with illustrations (though Text Publishing could surely have seen to better reproduction). Occasionally, the narrative sags, as when, in the mid 1920s, we are wearily reminded that ‘Stanley Melbourne Bruce remained Prime Minister’. I noticed a couple of mistakes. At the time Otto is writing about, Vida Goldstein was a devout Christian Scientist and not a mem-ber of Charles Strong’s Australian Church. Most alarmingly, Otto de-scribes Prime Minister J.C. Watson as ‘the first Labor head of state in the world’. How many times must it be reiterated that the Australian head of state was, and still is, the British monarch?

Comments powered by CComment