- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tapestry of trauma

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Memory Is Another Country: Women of the Vietnamese Diaspora is the product of a project financed by the Australian Research Council and undertaken by Nathalie Huynh Chau Nguyen, herself a refugee. Between 2005 and 2008 she and two co-workers (Boitran Huynh-Beattie and Thao Ha) recorded confidential oral testimony from forty-two Vietnamese women living in Australia, who are referred to only by their first names. They come from a range of different backgrounds, in terms of age, class and district, but all of them fled war and political upheaval before prolonged and painful transitions to Australia. Their narratives cover generations of war and its aftermath, from the French and Japanese occupations to American intervention and the 1975 fall of Saigon, and life in re-education camps thereafter. Many of the women made multiple escape attempts before reaching Australia – fourteen, in one case.

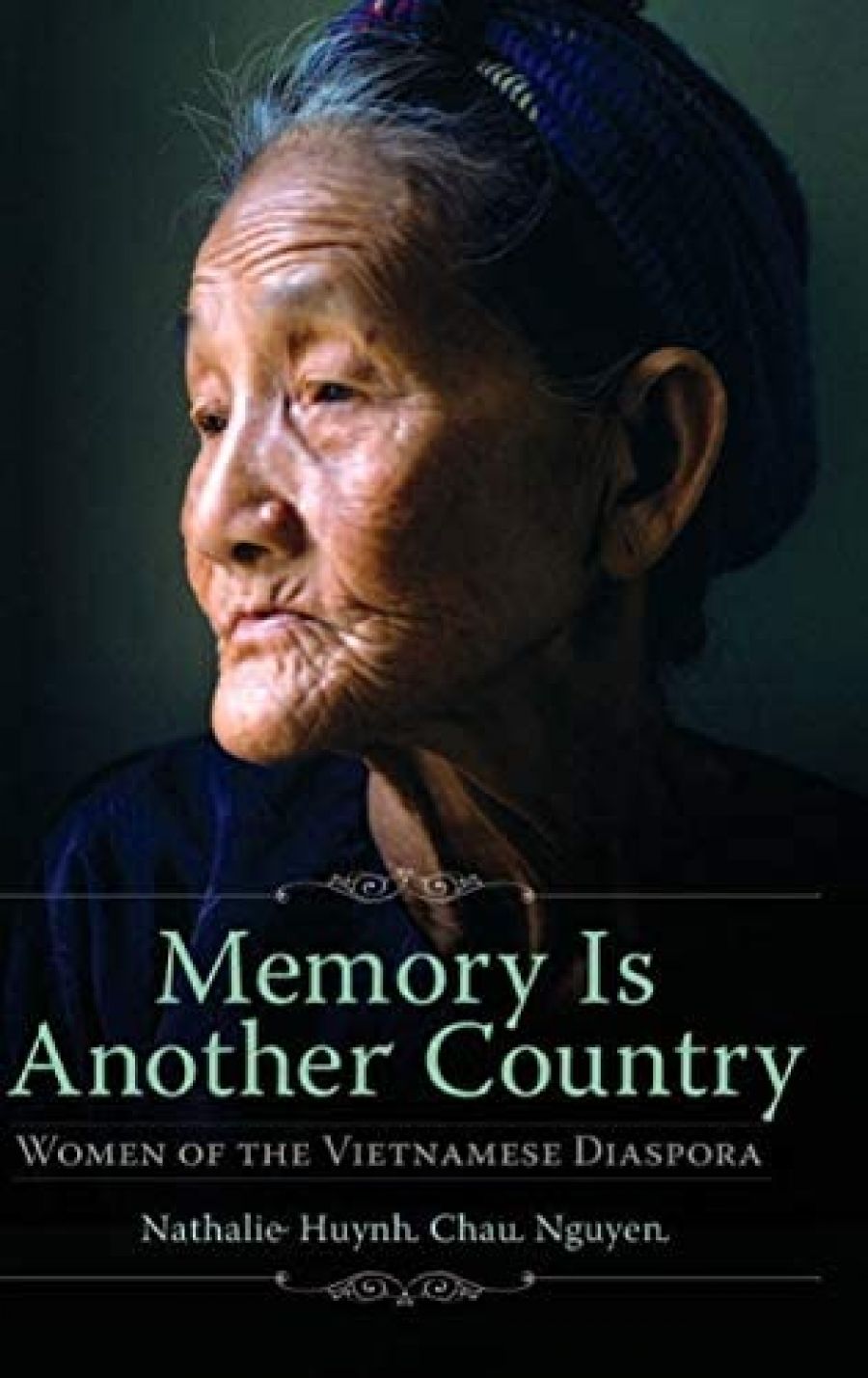

- Book 1 Title: Memory is Another Country

- Book 1 Subtitle: Women of the Vietnamese diaspora

- Book 1 Biblio: Praeger, $39.95 hb, 212 pp

In setting her framework, Nguyen writes of the problem presented by the unreliability of memory:

Memory’s very unreliability … has been identified as a strength by oral historians, since it provides clues about the relationship between past and present, and between individuals and collective memory. People reshape and reframe their memories to make sense of their lives. For refugees, the reappropriation of the past may reveal traumatic experiences and devastating loss, but the process of memory work may also be regenerative …

She describes escape by sea as ‘the defining narrative of the Vietnamese diaspora’, and notes that the majority of those who died during the flight from their homeland did so at sea. She claims that at least one hundred thousand boat people either drowned or were killed by pirates.

Growing up in Australia, I remember notices in the local Vietnamese papers commemorating entire families that had drowned at sea. Stories of great loss, for example, that of the woman who watched each of her seven children die one by one on the journey, are referred to in hushed tones in Vietnamese circles.

Nguyen relates in a matter-of-fact way the stories of some of her own relations who were lost at sea. One of the twenty-two faded photographs that illustrate the book depicts Nguyen’s relative Hoa and her cousin in Saigon, in 1970, a simple portrait of two pretty young women. In 1978 Hoa embarked on an escape attempt with her two daughters, aged seven and three, and her younger sister and brother. Their boat, carrying two hundred people, disappeared without trace. Hoa’s relatives, who had reached America and Australia earlier, waited a decade before abandoning hope.

Among the stories in Memory Is Another Country are those of women veterans of the southern army, the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF). Like Australia’s Vietnam veterans, who were often rejected by the society that sent them to fight, the Vietnamese who fought in southern ranks have been expunged from the history books of independent Vietnam. Their military cemetery was razed around 1975, with families scrambling to retrieve remains beforehand. Nguyen analyses the few available histories of the role of the southern army, but notes that the women’s units are barely mentioned. For some of the women interviewed here, army enlistment liberated them from the shackles of traditional Confucian culture, as well as giving them a vivid front-line experience of the conflict. Official denial means they have had to work to reconstruct their histories.

The author’s interest in the women soldiers was aroused after a Vietnamese colleague at Oxford, also a boat person, told her that his mother had served in the RVNAF as a paratrooper during her sixteen years of service. Thuy, as she was called, became one of her first interviewees and inspired the chapter ‘Women in Uniform’.

As with other military forces at this time, most of the women who enlisted were not combat soldiers, but were assigned to administrative and medical support duties. Three of the four women in this chapter carry strong memories of the military hospitals where they were posted. Quy recalls the ‘many deaths’ she witnessed, stating that she would see a healthy, good-looking young man one minute, then ‘the next minute, I’d find him in the morgue. That was considered normal in a time of war.’ Another ex-soldier relates that things she saw during her time as a nurse – particularly the sight of young women weeping over their dead husbands – frightened her off the idea of marriage.

Nguyen observes that many Vietnamese refugees ‘guard their memories with silence’. The chosen anonymity of the women who contributed these stories apparently resulted in the decision not to include them in the index, not even by their first names. The book is organised in a way that intersperses chunks of the narrators’ words throughout each chapter. This makes the reading experience rather dense. Without the index as a guide, there is a feeling of losing oneself in the memory-tapestry. But this is not a reason to desist from reading such a rewarding and moving book.

Comments powered by CComment