- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Christening the knife

- Article Subtitle: Ambivalent notes in a new portrait of Pugh

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Think of John Brack, or Fred Williams, and without effort or prompting a painting will come to mind. These names conjure up Brack’s urban figures with their blank yet expressive faces, or Williams’ minimalist landscapes. Instantly recognisable, they could have been painted by no one else. Yet their makers have never been celebrities. Brack’s Collins St, 5p.m. is more widely known than Brack the painter. Fred Williams always seemed too absorbed in his work to turn his face to the public. A portly figure in a suit, he was no one’s image of an artist. Arthur Boyd, so one of his friends wryly remarked, ‘sometimes backed shyly into the limelight’, but he was happiest away from the public gaze. Although the popular acclaim of the Ned Kelly paintings might well have obscured their creator, Sidney Nolan was tough and confident enough to emerge into a blaze of publicity (expertly kindled by John and Sunday Reed) and to withdraw when he pleased.

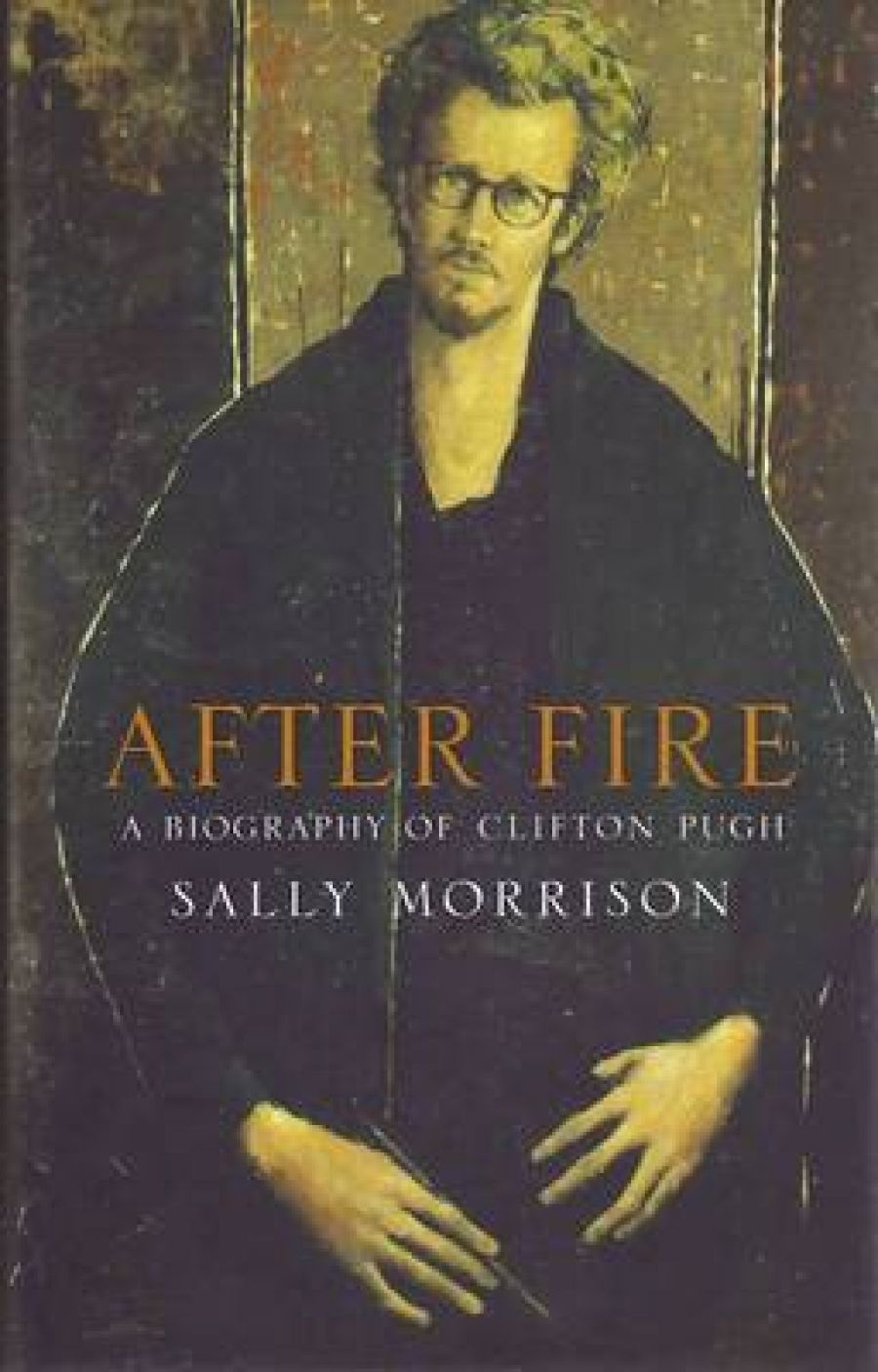

- Book 1 Title: After Fire

- Book 1 Subtitle: A biography of Clifton Pugh

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant Books, $65 hb, 592 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/after-fire-sally-morrison/ebook/9781742734514.html

Novelist Sally Morrison (who refused a proposal of marriage from Clifton Pugh) has read private letters and diaries, explored family history, interviewed friends, and consulted public records. She is intermittently present in the narrative, which might be seen as a courageous attempt to face the dark side of someone for whom she retained to the end a measure of love. Her perspective veers from an astringently critical assessment of the evidence to a sentimentality that looks like wish fulfilment.

Pugh’s story begins quietly. Born in 1924, he had a severe, war-damaged father, a doting mother, and, for his early years, a secure middle-class upbringing. He knew quite early that he wanted to be an artist, but after his father’s sudden death in 1938, the loss of family income, and the outbreak of war in the following year, he was too unsettled to develop his talent. He did, however, see the early work of Arthur Boyd, Sidney Nolan, John Perceval, and Albert Tucker in the Contemporary Art Society’s anti-fascist exhibition of July 1942. That was a revelation. It inspired Pugh’s first success: his Woman with mirror was accepted by the CAS in the same year, when he was just eighteen. War service followed, deferring his career in art.

By the end of 1944, Pugh was in New Guinea. Reading his diaries and letters home (held in the National Library), his biographer had to confront an appalling account of the brutal relish with which he killed a wounded Japanese soldier.

I stood by him and drew my knife and waited. He started to open his eyes again. So I plunged the knife into his chest about 2” just off his heart. He suddenly opened his eyes then groaned and started to thresh his arms. So I struck him again, only pushed in slowly this time. He moaned horribly, then I kicked him aside and left him to die in agony … I was happy. I had got my Jap and christened my knife.

This, so his biographer believes, was a key moment in Pugh’s life; something that shaped his view of self and of humanity. She links it with Pugh’s anti-war feeling of a later time, and laments that the ‘killer instinct’ overcame ‘the tender, innocent mischievous boy he used to be’. It is not certain when Pugh’s revulsion against war set in. Morrison quotes a 1981 interview in which he recalled a moment, soon after the killing, when he talked to a Japanese prisoner and ‘found he was fighting for just the same reason I was … I just wouldn’t fight any more’.

Yet Pugh did not leave the forces when the war ended. He volunteered to go to Japan with the Army of Occupation. He saw Hiroshima, reporting laconically that it ‘lived up to all that was said in the newspapers – just flat acres of rubble’. The self that emerges from this period is an unashamed racketeer: Pugh the opportunist. His letters record systematic and profitable dealings on the black market. He plundered a Shinto shrine, stealing a fourteenth-century painting. Later, he claimed to have set up a brothel, recruiting Japanese girls for his own use and profit. Compassion for the Japanese as fellow victims of war is not evident.

Morrison shows how Pugh rearranged his war memories. He claimed that he had been wounded in action, but this is not supported by hospital records of his admission with malaria. The ‘tender innocent’ of pre-war years has to be taken on trust. Morrison’s title offers more than one level of meaning. As well as its obvious reference to the fire that destroyed Pugh’s house in 2001, it may suggest a process of purification, by placing the murderous experience in the context of his campaigning against the Vietnam War in the 1960s. It may be that Pugh’s violent rages stemmed from struggles with conscience. It would be nice to think so.

All through the interviews with and about ex-wives and lovers, their anger and resentment come to the surface. His first wife, June, who took a job to support him while he painted, was summarily discarded; her successor, Marlene, while suffering from cervical cancer, was neglected; her illness brought out a ‘nasty streak’ in him. Judith, the third wife, recorded an episode when the drunken Clif attacked her and split her eardrum. It was ‘the only occasion he really laid into me’, she said forbearingly. Everyone agrees that he was kind to wombats.

That’s one of the puzzles of this book. If only half the stories of Pugh’s selfishness and abusive behaviour are true, it is a wonder that so many women put up with him. Morrison describes him as someone who loved women, but whose behaviour was often lecherous and coarse. He was too self-absorbed to be a good father. Some friends spoke warmly of the ‘real Clif ’. Questioned about Pugh’s self-promotion, Tim Burstall said: ‘I think he was pure in himself, really …’

Morrison is judicious in discussing Pugh’s art. She readily concedes some of his weaknesses, which include an uneasy mixing of genres, but points to an impressive number of fine, insightful portraits and many delicately observed landscapes. In a long and overdetailed book, the paintings sometimes get obscured, but Morrison’s perceptive comments are well worth tracing and considering.

Pugh’s drive to secure famous sitters took him into dubious company, at least for a committed supporter of the Labor Party. Morrison’s tolerance reached its limit when Pugh painted a notorious Queensland political figure: ‘I couldn’t imagine how you could paint Russ Hinze’s portrait without being Hinze’s mate.’

Yet it is clear that Morrison retained a large measure of affection and admiration for Pugh. The biography, an immense labour, has taken her seven years. Some editorial trimming would have helped. We don’t, for example, need to wonder whether Pugh took a bus to Adelaide in December 1945, or to be told that his fiancée June was then staying with her Aunt Vera. But the period background is well managed and useful.

The book is valuable as Australian social history as well as biography, for its record of changing times: the sexual revolution of the 1960s, the anti-war protests of the Vietnam years, and the early environmental movement. Whether or not Morrison intended it, however, the Clifton Pugh of these pages emerges more as opportunist than true believer.

Comments powered by CComment