- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Dance

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Last year marked the centenary of Robert Helpmann’s birth. Apart from a tribute at the Helpmann Awards ceremony – the ‘Bobbies’ – in July 2009, no Australian performing arts company celebrated the anniversary of this polymorphous artist and early advocate for a national artistic life created by Australians, not by northern-hemisphere exporters. Two new books and a vibrant touring exhibition went part of the way towards providing a fitting tribute.

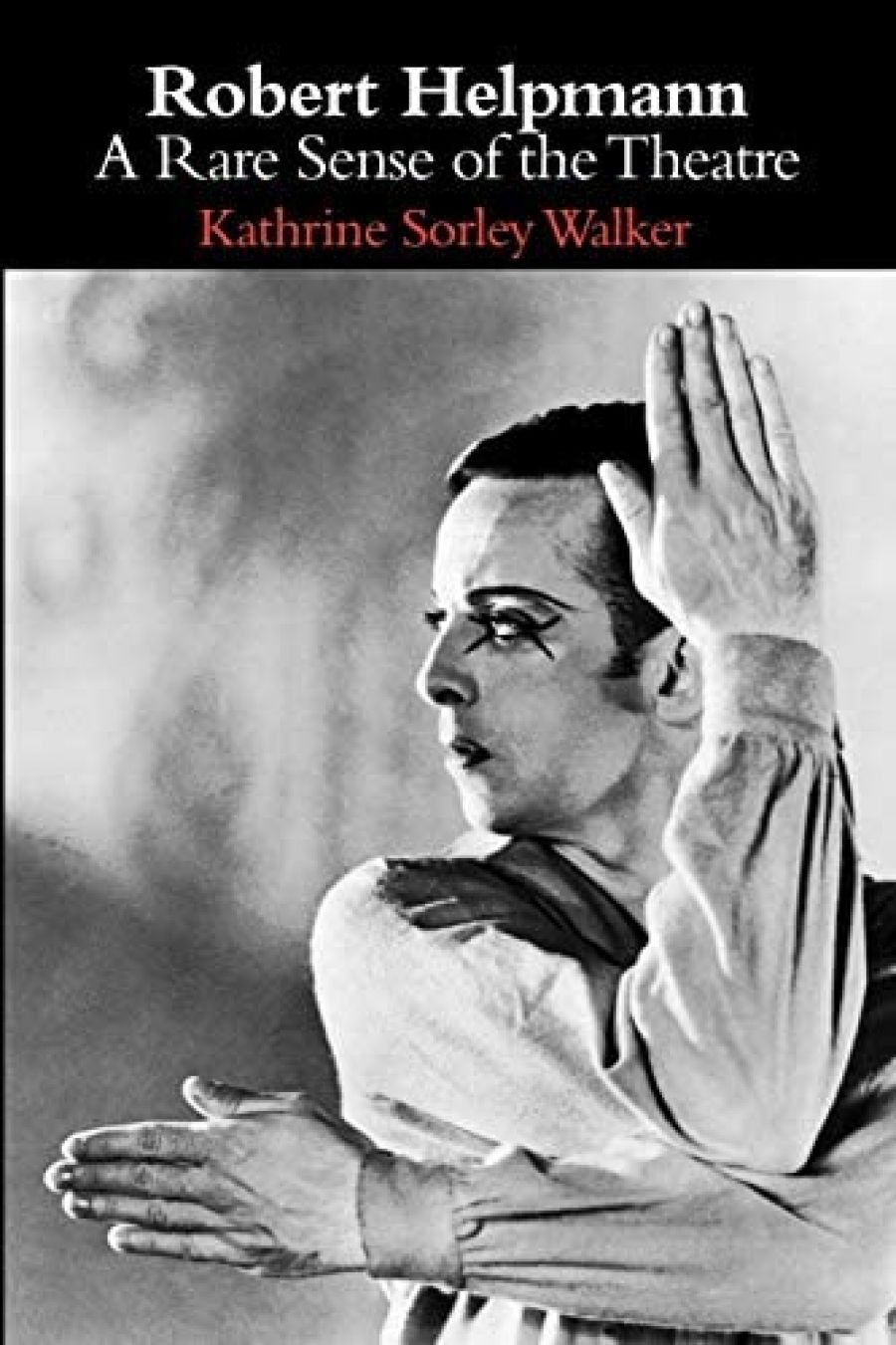

- Book 1 Title: Robert Helpmann

- Book 1 Subtitle: A rare sense of the theatre

- Book 1 Biblio: Dance Books (Footprint Books), $29.95 pb, 205 pp

Of the three, Bobby Dazzler!, Christopher Smith’s show at the Queensland Performing Arts Centre’s Tony Gould Gallery, was best able to bring both man and artist to life. Here, in a vibrant, stage-like space divided by coloured floating gauzes, one could find Helpmann explained in photographs, texts and video projections. Each medium recalled the diverse milieux he inhabited as a star and intimate and cheerful ‘uncle’ to other actors’ children. Documentary footage showed him playing a trio of villains in The Tales of Hoffman film with Moira Shearer, in his prime with prima ballerina assoluta Margot Fonteyn or stealing children in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. There was more: Shylock, opposite Katharine Hepburn as Portia; the Bishop of Ely in Laurence Olivier’s film of Henry V; the fantastical Dr Coppelius and a virago-like step-sister in Frederick Ashton’s Cinderella. The sharpest Australian perspective came not from Rudolf Nureyev and the Australian Ballet’s Don Quixote (1970) or Helpmann’s own ballets The Display (1964), Yugen (1965) and Sun Music (1968), but from an excoriating scene from Justin Fleming’s play The Cobra (1983), directed by Richard Wherrett, with Helpmann, aged seventy-four, as the geriatric ‘Bosie’, Lord Alfred Douglas.

After seeing Bobby Dazzler! I expected to gain something similar from Kathrine Sorley Walker’s Robert Helpmann: A Rare Sense of the Theatre, and to a large degree I did. Sorley Walker – a critic for Playgoer (1951–56) and the Daily Telegraph (1962–95), and the author of Ninette de Valois: Idealist without Illusions (1987, 1998) and De Basil’s Ballets Russes (1983), the definitive history of that company – presents a long view of Helpmann’s career and of his myriad achievements in dance and drama. She also considers opera productions, festivals and films in the context of his prodigious career. However, Robert Helpmann, the second biography in a year, similarly fails to illuminate the multifaceted personality that friends and relations adored but that others found self-centred or aloof, and often hostile. (Ian Britain reviewed Anna Bemrose’s Robert Helpmann: A Servant of Art in the December 2008–January 2009 issue of ABR.)

As with Sorley Walker’s 1957 account of Helpmann, which was subtitled ‘An illustrated study of his work, with a list of his appearances on stage and screen’, this volume reads like a catalogue raisonné, alternating fine descriptions with generous commentary on Helpmann at work. Inevitably it intertwines Helpmann’s history with that of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, which he joined in 1931, one year after its creation by Ninette de Valois. Helpmann’s maturing into both a noble and character dancer took place as Albrecht in Giselle and in de Valois’s ballets. The range of his roles was prodigious: Satan in Job (1935), the Rake in The Rake’s Progress (1937) and the comical theatre owner Mr O’Reilly in The Prospect Before Us (1939), perfect entertainment for Londoners before the Blitz. For the Old Vic Theatre, part of the Sadler’s Wells, Tyrone Guthrie directed Helpmann’s Oberon in a magical Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1937, and Hamlet in 1944. The latter came about only after Helpmann created his wordless Hamlet ballet to Tchaikovsky’s eponymous fantasia on a wild, surrealist set by Leslie Hurry. Although his performance in the ballet divided critics, one pronounced it one of the greatest ever. Sorley Walker’s advantage over younger writers becomes obvious after a few pages. As a schoolgirl, and repeatedly in later decades, she saw Helpmann in many of his roles, thus allowing her in maturity to re-evaluate his oeuvre and its impact.

For the second part of Helpmann’s career, the Australian years, Sorley Walker treats his early local productions with particular care. The Australian Ballet performed The Display and Yugen during its first international tour in 1965. Like the much-maligned Elektra of 1963, with its erotic backdrop by Arthur Boyd, for the Royal Ballet, these performances received some appalling reviews, but also some praise from those critics who, in Sorley Walker’s view, were brave enough to speak up in the face of such hostility. The tour was a thrilling success, despite the mixed reviews, and the board decided to draw on Helpmann’s international cachet by appointing him Peggy Van Praagh’s artistic co-director of the company for three months a year.

This is where Sorley Walker’s account begins to feel less substantial. I suspect only an Australian or long-term resident could interpret Helpmann’s entry to the company (Van Praagh was furious) or, more broadly, his re-entry into Australian society. His first visit after twenty-three years was as part of an Old Vic tour of The Merchant of Venice, Measure for Measure and The Taming of the Shrew, with Katharine Hepburn as Portia, Isabella and Kate, respectively. Reviews were mixed, especially for Hepburn, but Helpmann had ‘come home’, a national hero to boast about.

The second Australian phase would prove more troublesome as Helpmann took on heavier administrative responsibilities. Not that this troubled him; Helpmann thrived on hard work, touring international legends around the world and making a number of films. Some were mediocre, as was his foray into the pop music scene, which embarrassed some onlookers. What infuriated Helpmann most was his cavalier treatment at the hands of boards dominated by businessmen at the Australian Ballet, the Adelaide Festival (of which he was director in 1970) and the Old Tote Theatre Company, which closed just as it was about to open under his direction. While such conflict might seem ripe for analysis, Sorley Walker may not have felt qualified to expand on the bare facts. Australian writers might be disinclined, too, for the present situation is not all that different. Many involved in arts governance today seem to believe that a rosy balance sheet is the most important consideration. Helpmann would be appalled.

Two other themes warranting further study are Helpmann’s relationships with his parents, Sam and Mary, and with his long-term lovers Michael Benthall (from 1939) and Christopher Brown (from 1970). Sam made the move that got young Bob to Sydney and to Anna Pavlova’s company as an apprentice, then to the J.C. Williamson Company. The catalyst for this translation was the boy’s effeminate manner and his precocious theatricality, which reached a climax in 1920 when Helpmann, aged eleven, danced in drag and on point at an Adelaide gala concert for Nellie Melba. At the end of the piece, as the audience encored him, he tore off his curly blond wig to expose his identity and achieve the surprise twist he had intended. The Adelaide Establishment was aghast, and children were forbidden to have anything to do with him. In an oral history recorded more than forty years later by the National Library of Australia, the humiliation of those early years was still palpable. After Sam’s death in 1927, Mary, a gifted amateur singer and actor who had inculcated her love of the arts in her son, assumed control and watched him flourish, every bit as ambitious for her brilliant child as he later became.

Sorley Walker’s account of Helpmann’s first major love affair is pertinent, but its brevity leaves one wondering about the partnership: ‘The Helpmann/Benthall relationship had firm ground in their mutual passion for the performing arts for music and design; and had it been possible at the time, it would certainly have resulted in a Civil Partnership.’ Benthall, who died in 1974, features often in the book, but remains shadowy. Of Christopher Brown there are only brief mentions. As for Helpmann’s intimate relations with Fonteyn, Hepburn, Vivien Leigh and Margaret Rawlings, who introduced him to de Valois, Sorley Walker does not speculate. Meredith Daneman, in Margot Fonteyn: A Life (2004), paints all of these attachments as sexual, substantial and self-serving. Daneman writes: ‘the presents he showered on the [Oliviers] caused Ashton to snipe: “That’s not generosity, that’s investment!”’

Robert Helpmann often said that he lived to work and create things of beauty in the theatre. Work, like ambition, had become a habit. Towards the end of his life, he toured Sydney Leagues clubs in plays with his pals Googie Withers and John McCallum (who died last month). After directing another operetta and film, Helpmann directed Joan Sutherland in I Puritani (1985), then danced one of his greatest roles, the decrepit Red King, in de Valois’s Checkmate with the Australian Ballet in 1986. I thought he would expire on stage, but death came a few months later, on 28 September 1986. Anyone who saw those performances will never forget him. But who will write his life?

Comments powered by CComment