- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Anthony Blanche stands on the high balcony with a megaphone. With practised stammer he recites The Waste Land to puzzled undergraduates walking below in Christ Church Meadow. ‘How I have surprised them!’ he assures the other Old Etonians gathered for languid lunch in Lord Sebastian Flyte’s rooms. In this single image, Evelyn Waugh fixes Blanche in our memories – privilege, aesthetes, the creeping arrival of bewildering new art to the Oxford of 1923.

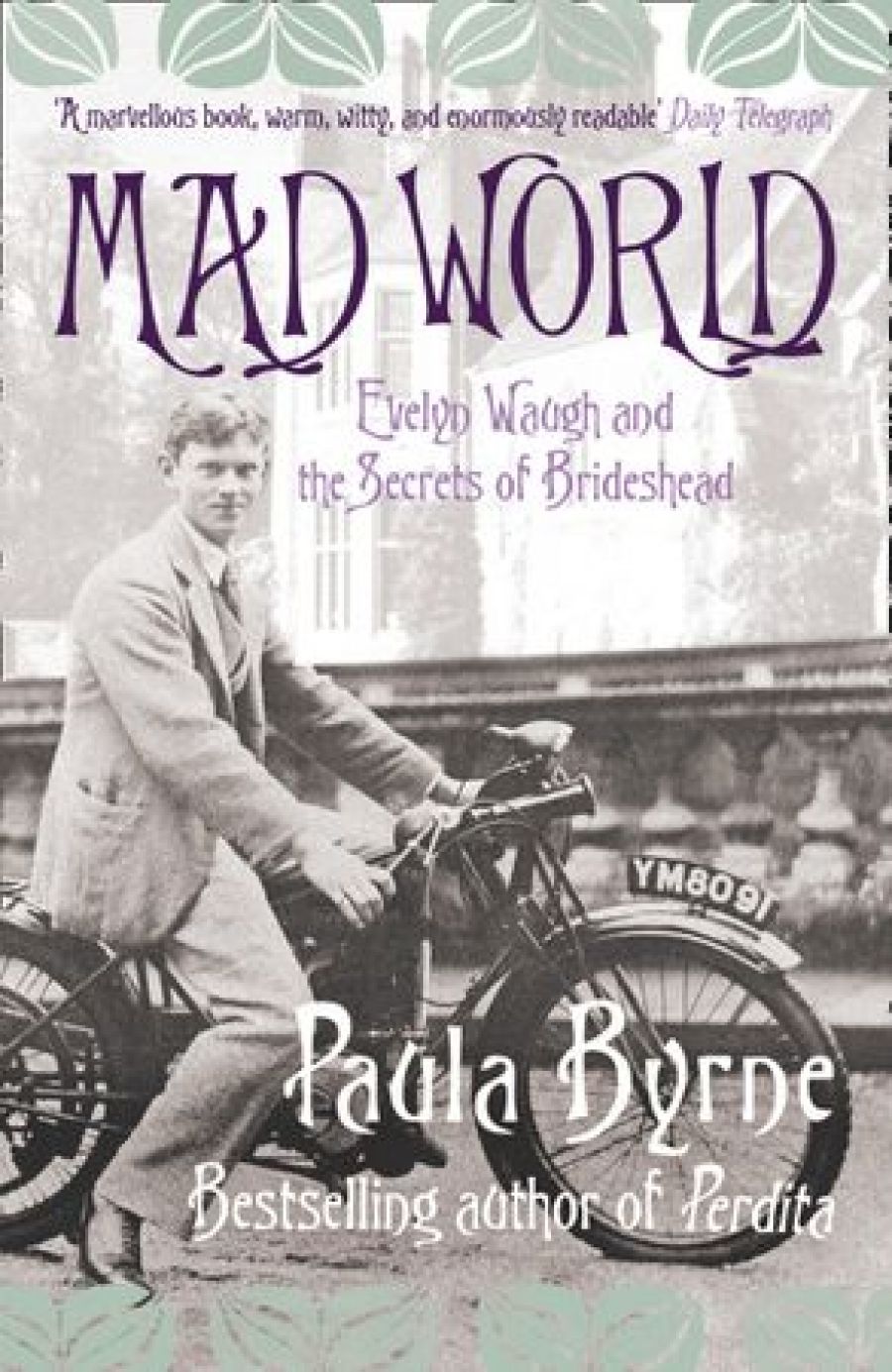

- Book 1 Title: Mad World

- Book 1 Subtitle: Evelyn Waugh and the secrets of Brideshead

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperPress, $49.99 hb, 384 pp

Art converts experience into the universal. Throughout Brideshead Revisited (1945), Waugh lifts prosaic detail from his life and, like alchemy, transforms the base into something precious. In telling the story of two young men who meet at Oxford, Waugh traces the consequences over the next decades for his characters, their families and a lost world.

Others have worked the same material. Anthony Powell was at Oxford only a year or so later than Waugh, and knew many of the same people. Like Waugh, Powell was a member of the Hypocrites’ Club, with Harold Acton. He too may have heard The Waste Land (1922) drift across the Meadow. Powell’s fictional memoirs, A Dance to the Music of Time (1951–75), run to twelve volumes, providing scope to explore personalities and patterns over time.

The contrast favours Waugh. Though Powell has much to offer, he cannot match his more famous contemporary for power or compression. A Dance to the Music of Time still finds a modest audience, while Brideshead Revisited continues to intrigue new audiences, helped enormously by the famous Granada Television production (1981) and the more recent film (2008).

Evelyn Waugh was born in 1903. His generation, too young to fight in World War I, was raised in the shadow of conflict before coming to maturity in the 1930s, that ‘low, dishonest decade’. His was the world of boarding schools, distant parents and endless paeans to the glorious dead. Later would follow economic depression and yet more war.

Amid this bleak roll-call, university years promised a golden moment of escape. For those at Oxford, an all-male college offered companionship and an invitation to enjoy life before the dull certainties of adulthood. Few have embraced the possibilities of youth with Waugh’s gusto, drinking, acting and forming passionate attachments with young men. Among his close friends was Hugh Lygon, at Eton with Anthony Powell, and the model for Sebastian Flyte.

The opening chapters of Brideshead Revisited are a hymn to this recalled idyll. It is the university, rather than the Catholic theme, that attracts Waugh’s most memorable prose – Oxford as Arcadia, the city aquatint, with spacious and quiet streets where men walked as they had in Newman’s day, autumnal mists and grey springtime, the skyline of gables and cupolas, the city on summer days exhaling the soft airs of centuries of youth.

This Oxford offered hidden doors opening to an enclosed and enchanted garden. There, Waugh discovered not only love but class – the aristocrats who would drift through his novels in various disguises. Later, Waugh would be accused of falling under the spell of the titled. Yet even at his most entranced, there remains detachment. Waugh was impish, from a solid middle-class family. He could admire the great families, but never join them. He traded on wit, gossip and a capacity to be a friend rather than lover of the unhappy aristocratic daughters who filled his world. The eye was too sharp to miss folly and failure.

In Brideshead Revisited, the narrator leaves Oxford without completing his degree, to begin a career as a painter. Waugh managed to finish, securing an undistinguished third before finding work as a schoolteacher. Literary success followed quickly. His first novel, Decline and Fall (1928), and its successor, Vile Bodies (1930), captured the ‘bright young things’, and Waugh found himself young and famous in the London of Noël Coward, Aldous Huxley, Nancy Cunard and Michael Arlen.

When an early marriage failed, Waugh took to travel. Adventures in North Africa and South America would be funded by journalism and find their way into the novels. Waugh was building a repertoire of experience on which to draw. Home in England, he would book into a hotel or borrow lodgings on an estate, and write furiously. Into his thirties, Waugh produced the funniest and most cutting satire of his generation. Many endure; Scoop (1938), based on his time in Abyssinia, remains the great comedy on journalism.

With a successful second marriage, children and financial success, Waugh settled in the countryside. But as war approached, he pressed contacts for a chance to serve. Waugh would prove remarkably fearless when finally called to action in the last year of the war – experiences recounted in the Sword of Honour trilogy (1952–61). But much of the war proved frustrating and tedious, as British forces began the long, slow build toward a European invasion. Military service was often a stretch of boredom, with pointless military drills and enforced idleness.

Following a minor parachuting accident – Waugh was approaching forty – he sought leave to complete a novel. Brideshead Revisited took six months to write. The mark of wartime is clear, from the prologue as an older Charles Ryder (exactly Waugh’s age) recounts the drudgery of moving camp, to the loving description of a meal in Paris, every dish described in lingering detail.

The burden of Mad World is that Waugh drew closely on a real family for his account of doomed Catholic nobles. The Lygons were an ancient lineage, with an unbroken line from the time of William the Conqueror. They featured prominently in accounts of Empire. Lygon Street, in Carlton, is named for an earlier generation, and William, the seventh earl, served briefly as governor of New South Wales. Waugh knew Hugh Lygon and his famous teddy bear from Oxford, and later met Hugh’s elder brother Lord Elmsley, his three sisters the Ladies Lettice (really), Mary and Sibell, young brother Dickie at the family house, Madresfield. The family saga provided the architecture for Brideshead Revisited.

In the novel, Lord Marchmain, the paterfamilias, has retreated to Venice, where he lives with his Italian mistress, Cara, while his pious wife remains in the family house. A visit by Sebastian and Charles provides a chance for life on the Lido and afternoon light on water. It also provides Cara a set piece speech about the ‘romantic friendships’ of young English gentlemen. ‘They are good if they do not go on too long,’ she warns Charles bluntly. Sebastian, in love with his childhood, drinks too much in order to avoid the responsibilities of adulthood. As Waugh moved from loving boys to women so will Charles, while tragic Sebastian is doomed to drunkenness and death somewhere in North Africa.

Waugh obscured key features of his models. Hugh Lygon would die in a car accident in Germany, after many failed attempts to shake his alcoholism. More significantly, it was not an Italian mistress who detained his father, William Lygon, the seventh earl of Beauchamp. Rather, the earl’s energetic pursuit of younger men, often servants in the family home, and the machinations of an aggrieved relative, made Lygon ‘the last historic, authentic case of someone being hounded out of society’. Faced with prosecution for obscenity, Lygon did not follow Oscar Wilde into prison but caught the night boat to France. He would spend many of his later years in Sydney, living at Darling Point and joining the crowds at Bondi Beach.

The suggestion that Waugh drew from materials near at hand is unremarkable, and this followed his usual pattern. In Mad World, Paula Byrne emphasises the close fit, with Mary (‘Maime’) Lygon as the inspiration for Julia Flyte, the quattrocento beauty who replaces Sebastian in Charles’s affection until Lord Marchmain returns to England to die. His deathbed sign of the cross returns Julia to religion, and Charles to an empty life. ‘I’m homeless, childless, middle-aged, loveless,’ Ryder tells his adjunct. It is not what one would have foretold in those glorious days at Oxford.

Byrne demonstrates that Waugh found inspiration in the world he knew. Her thesis requires a somewhat narrow reading of the novel, and little attention to the Catholic messages that appear Waugh’s principal reason for writing. The plot requires a twisting logic, from wartime camp through two decades and back; and this departs significantly from the trajectory of the Lygon family. To fit this stricture much is excised, including the earl’s liberal politics. To carry the burden, Waugh’s plot requires a symmetry missing in the messy circumstances of lived reality.

Art creates its own truth. The Oxford Waugh remembers is hard to find in novels by others from the period. Anthony Powell meditates from a similar vantage point at Balliol for A Dance to the Music of Time, but without the glorious effect. Perhaps because Waugh regretted nothing of his university days, he could capture without hesitation the first fine rapture of youth. Bliss requires inspiration and technical skill, and even at his most cantankerous Waugh is a fine writer.

A further triumph awaited – The Loved One, published in 1948. But Waugh would become increasingly dyspeptic, out of sympathy with the times, prone to the effects of alcohol and sleeping pills. What began as his amusing impersonation of a cranky squire became the persona, as Waugh grew into his mask. Disappointments with postwar Britain were mirrored in religious matters, as Vatican II undermined the church he had embraced many decades before.

The inspirations for Brideshead too would find life a challenge. The earl of Beauchamp died of cancer in New York, in 1938. His wife died some years earlier, estranged from her children. Her son proved the last earl, the title expiring on his death in 1979. The beautiful Maime would be unlucky in love and succumb in 1982 after a long struggle with alcohol and mental instability.

Mad World sets itself the task of matching a novel with history, and succeeds on its own terms. The price is a literal-minded reading of Brideshead Revisited, a tendency to repetition, inadequate references and a woeful index. The author records, but does not heed, the frontispiece to the original edition, in which Evelyn Waugh said, ‘I am not I, thou art not he or she: they are not they’.

Brideshead Revisited carries all the traces identified by Paula Byrne, but is more. The shadows behind the text are interesting, but cannot illuminate how Waugh surprised us, and does still.

Comments powered by CComment