- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Stealing Picasso is an art heist caper based on the sensational theft in 1986 of Picasso’s Weeping woman from the National Gallery of Victoria. The crime, attributed to a nebulous gang of militant aesthetes calling themselves the Australian Cultural Terrorists, remains unsolved. Anson Cameron, a Melbourne writer best known for the novel Tin Toys (2000), takes this historical loose end and runs with it, discarding all but the most cursory details of the source story.

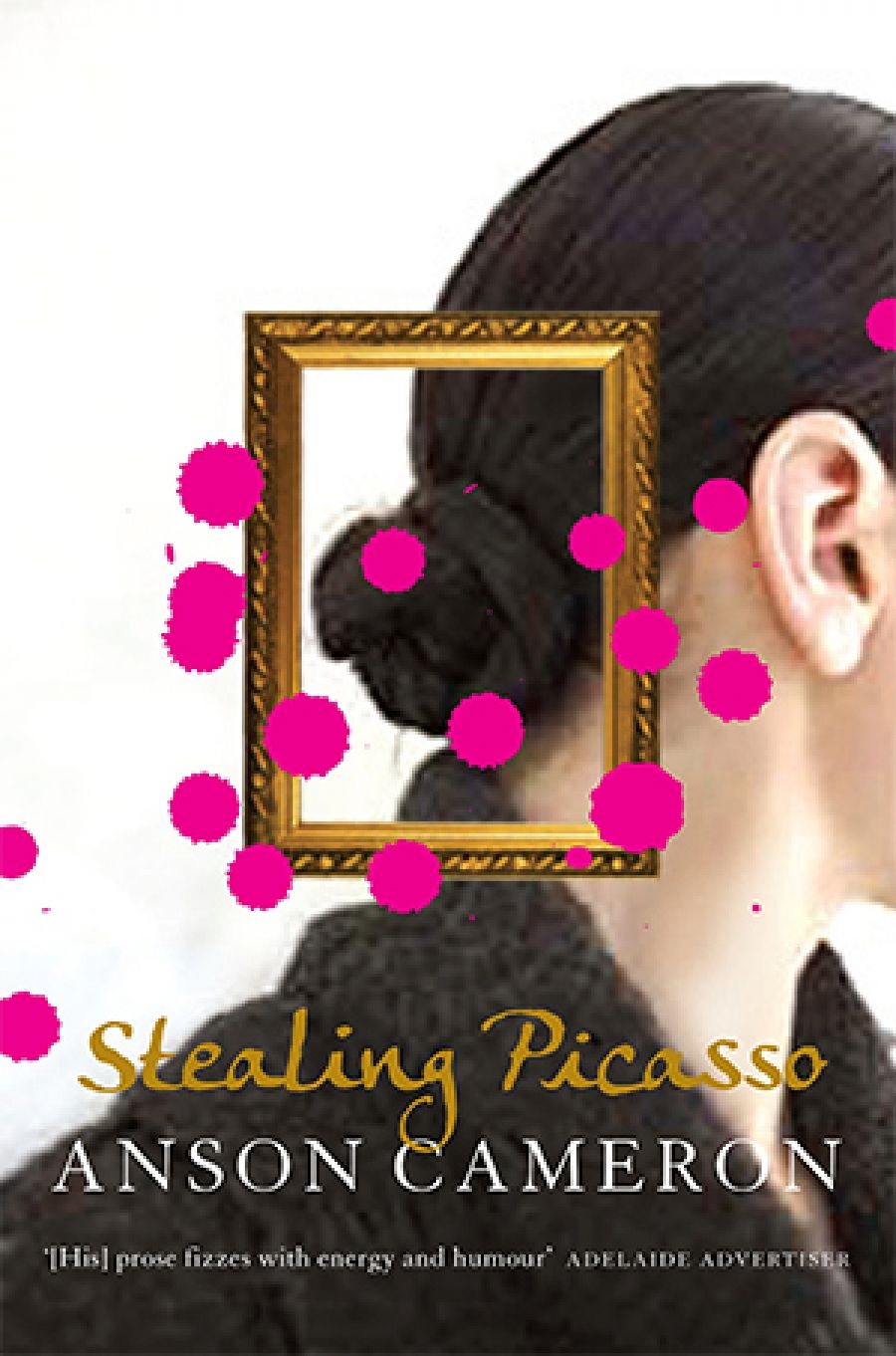

- Book 1 Title: Stealing Picasso

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $32.95 pb, 256 pp

The story begins inside the NGV – depicted here as a kind of taxpayer-funded Gormenghast, ‘a mediaeval fortress, complete with moat’ – in the rooms of the School of Art. This is a grungy, testosterone-heavy institution, presided over by Turton Pym, an erstwhile peer of Brett Whiteley and John Olsen. Pym’s talent having proved modest, he now seeks to assuage his bitterness by launching a generation of Pym-schooled painters.

Harry Broome is Pym’s most promising student. Ambitious but lacking direction, Harry falls under the spell of Mireille, a beautiful older woman. After various twists and turns, Harry, Turton and Mireille conspire to make off with the NGV’s recently acquired Picasso and to sell it to billionaire Laszlo Berg. (Almost every character in Stealing Picasso is burdened with a zany – but not especially funny or clever – name; Harry’s classmates in clude such unlikely personages as Sedify Bent, Pasquale Knapp and Roland Loader.) Naturally, the crime doesn’t come off as planned and the conspirators are drawn into a convoluted adventure involving betrayal, bikies, and an out-of-work Michael Jackson impersonator.

Stealing Picasso is assembled with enthusiasm, but the result is a mediocre concoction. Cameron’s figurative language is often clumsy: ‘A guy like this, with a broken dream, has a head full of shards of reminiscence sharp as glass’; ‘In Melbourne on a good spring day a sun sits on every car along every street’. Cameron’s use of the present tense, presumably to generate pace and immediacy, is paradoxically distancing. The narration often reads like a running commentary, an effect that renders unwieldy Cameron’s efforts to imbue his narrative with intellectual depth.

The sketchy characterisations wouldn’t be a problem if they contained an ounce of vitality. Protagonist Harry is purported to be brilliant and thoughtful, but he seems lifeless and a bit of a dill. Mireille is two parts Susan Sontag to three parts femme fatale, amounting to an unconvincing fantasy figure. Despite her alleged experience and sophistication, she is prone to naïve Euro-English syntax, describing a bikie gang as ‘a motorcycle gang of hoodlums’, for instance. The native English-speaking characters’ dialogue is clunkier still, especially when Cameron tries to evoke criminal cool. ‘I’m in the same boat as Coke,’ a bikie chief announces. ‘You advertise you’re the real thing, you got to be the real thing or they close you down. You advertise yourself as a brutal sonofabitch, you got to be carnage personified.’

Pym is a potentially interesting character; even his name, redolent of Poe, is fitting. Pompous, libidinous, Pym ‘speaks with the authority of failure’. Unfortunately, he also speaks with the same weird hollowness as Cameron’s other characters. ‘As soon as you shape up to the canvas the fight begins,’ quoth teacher Turton. ‘You either win or Failure wins. There is no honourable draw.’ Oddly, Turton’s students don’t spontaneously abandon class en masse but this is, as noted, a work of imagination.

Stealing Picasso’s satire is feeble. Cameron’s caricatures of institutionalised complacency and corruption are tepid: the NGV director, Weston Guest, is a preening alpha male; the gallery’s ruffian packing staff play a stoned game of pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey with a minor Giotto. It is often difficult to know what, if anything, is being satirised. At one point, Harry is working on a portrait of Mireille: ‘[M]aybe he should strip her off, paint her bare-breasted, then surround her with bears and have her laughing at them. Not circus bears, angry bears from the deep forest. Sit her outdoors, bare-breasted, laughing at these bears with their furrowed muzzles.’ This might sound preposterous; to Cameron’s supposedly snobbish NGV director it is ‘an extremely clever trope’ that he might consider purchasing. Is he taking the piss, or is Cameron?

Uncertainty of this kind pervades Stealing Picasso, the result of a niggling discrepancy between Cameron’s apparent intention and his accomplishment. Humour is signified but rarely delivered; the plot is elaborate but too sluggish to be suspenseful; the flimsy characterisations and stilted dialogue undermine Cameron’s excursions into sincerity. Stealing Picasso raises the occasional smile, but it isn’t art, not even close.

Comments powered by CComment