- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Dan Rule reviews 'How to Make Trouble and Influence People' by Iain McIntyre

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Cheek Politics

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Poor communication has long been activism’s Achilles heel. Engaging the wider populace and influencing opinion rely as much on the effective, reliable delivery of a message as on well-organised ideas and events. We may be loath to admit it, but intelligent public relations can aid any pursuit – advocatory, activist, or otherwise.

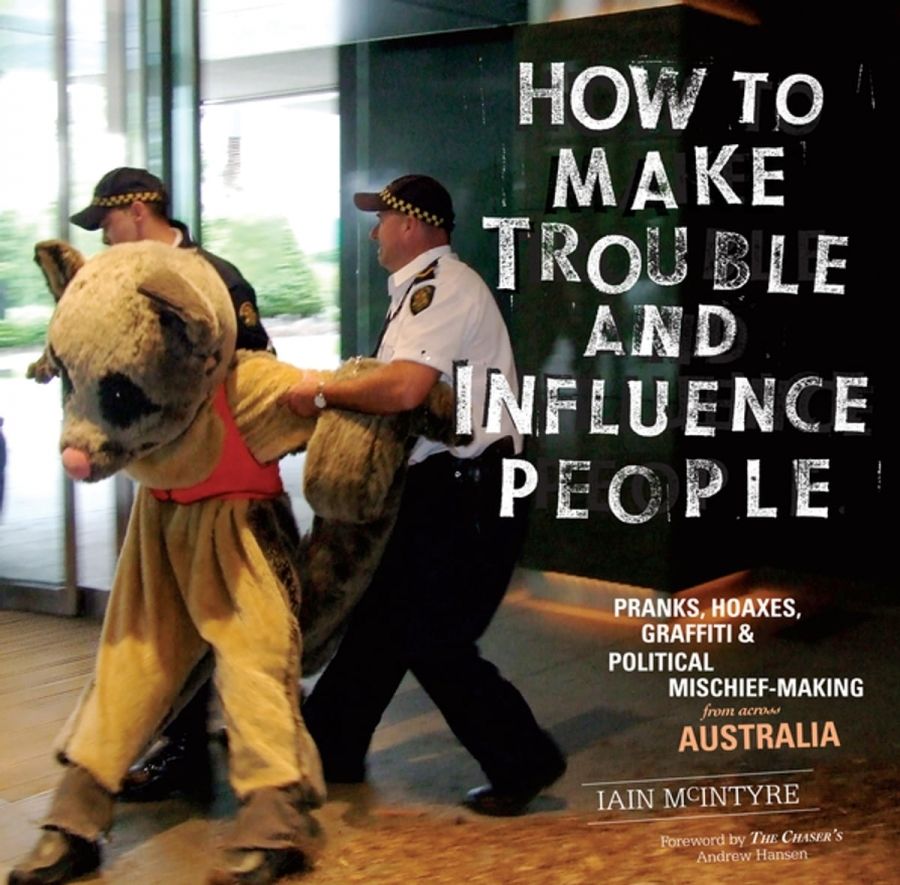

It is from this perspective that the expansive new publication How to Make Trouble and Influence People: Pranks, hoaxes, graffiti & mischief-making takes its cue. Compiled and written by Melbourne writer, zine-maker, and community radio presenter Iain McIntyre, this vividly illustrated volume documents not only an unofficial history of Australian protest, activism, and all-round cheek, but the connections between political trouble-making and its ability to influence popular opinion. It succeeds, for the most part.

- Book 1 Title: How to Make Trouble and Influence People

- Book 1 Subtitle: Pranks, hoaxes, graffiti & political mischief-making

- Book 1 Biblio: Breakdown Press, $29.95 pb, 276 pp

Comprising myriad compact, dated, encyclopaedic entries, a wealth of photographs and illustrations, plus fourteen expanded ‘conversations’ with Australian troublemakers – including John Safran, anti-apartheid activist Meredith Burgmann, and anti-uranium activist and Arabunna elder Uncle Kevin Buzzacott – there are several perspectives at play within How to Make Trouble. While McIntyre has his own agenda and seems at pains to cast Australian political mischief-making as part of meaningful cultural lineage, ‘informed by a commonly held belief on the Left that social progress does not emanate from … ‘enlightened’ politicians, but instead derives from grassroots resistance’, he is willing, to his credit, to allow the book’s many subjects and interviewees to diffuse his own editorialising.

The question-and-answer ‘conversations’ are by far the volume’s strongest and most insightful component. McIntyre draws on a broad sweep of troublemakers, from public political artists such as the Buga-Up collective, which made its name ‘revising’ advertising billboards and disrupting tobacco-sponsored events through-out the 1980s and 1990s, to activist performers such as the John Howard Ladies’ Auxiliary Fan Club and drag satirist Pauline Pantsdown. Interviews with Safran and The Chaser’s Chris Taylor make for fascinating reading. While detailing the logistics behind some of their most infamous pranks – including The Chaser’s APEC Summit security breach – interestingly both Taylor and Safran refute the suggestion that their work holds activist implications, instead framing it in terms of entertainment and method acting.

McIntyre’s conversation with activist Dave Burgess, who, along with Will Saunders, made international headlines when they emblazoned the slogan ‘NO WAR’ in red paint on the Sydney Opera House in March 2003, makes for perhaps the most engaging passage in the book. Aside from the thrilling account of scaling the Opera House, the dialogue puts a rational and human face on a controversial deed that was subject to histrionics and obloquy in the mainstream press. Importantly, the conversation also considers the action’s influence and scope of the public response.

Any reservations concerning How to Make Trouble rest with the main body of text: the historical listing and brief descriptions of uprisings, protests, pranks, and the like. There are many inspiring, elucidatory, and hilarious accounts. The tale of four activists preventing a huge US military aircraft from landing at Alice Springs by riding their bicycles onto the runway, not to mention Magistrate David Heilpern’s dismissal of a charge against dancing activist group the Tranny Cops for impersonating police on the grounds of a ‘Village People-style defence’, are fine examples. That said, the collection could have done with some serious culling. While the anecdotal material gives the book its gritty flair, many of the entries are more like undergraduate hearsay, detailing mischievous or seditious acts and ignoring any meaningful resolve or potential sphere of influence. Inclusions such as ‘An imaginative shoplifter’ seem petty examples of sticking it to ‘the man’, and risk alienating readers.

The book’s foreword, by The Chaser’s Andrew Hansen, echoes the crucial dichotomy between creative and non-creative activism. Protestors ‘who scream … and chuck rocks and smash stuff … will have a hard time changing the average person’s mind,’ he writes. ‘That’s where imaginative, inspiring troublemaking can help.’

While not all of How to Make Trouble and Influence People lives up to both of its contended ambitions, the moments that do offer a feisty, perceptive, and rational dialogue on our diverse history of rebelliousness.

Comments powered by CComment