- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

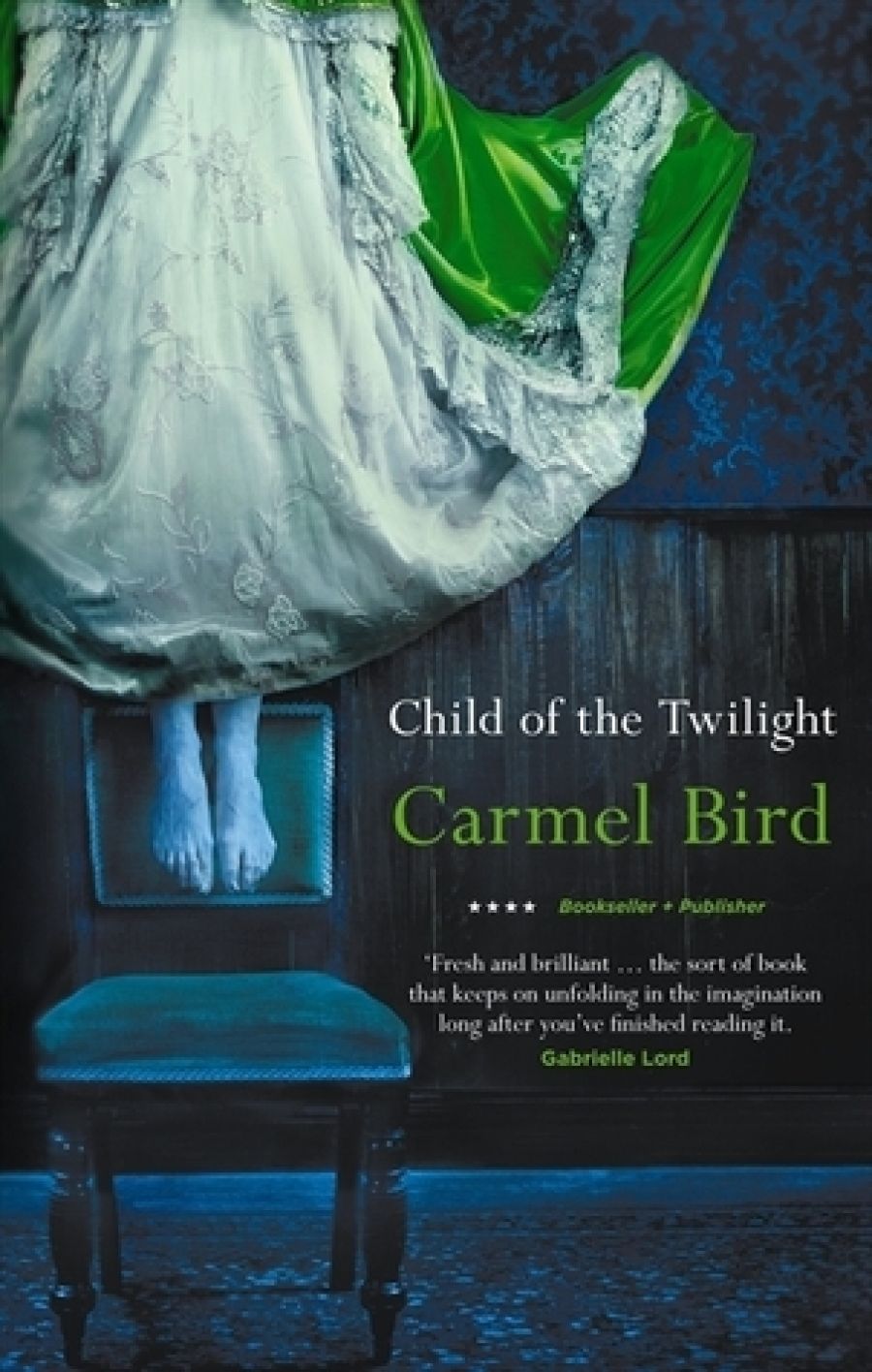

- Custom Article Title: Gillian Dooley reviews 'Child of the Twilight' by Carmel Bird

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Pagan charm

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The mystique of the Roman Catholic Church has been thoroughly exploited by the likes of Dan Brown and writers of the medieval monastic murder mysteries that gained a certain popularity following the English publication of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose in 1983. Carmel Bird’s latest book contains a mystery, though not a murder. It is set mostly in 2001, but monks, convents, rosaries, black madonnas, and miracles fill the pages of The Child of Twilight, along with artificial insemination and air travel.

Sydney Peony Kent, the narrator, is the product of assisted reproductive technology, both of her genetic forbears being anonymous donors; her parents, habitually and oddly bundled together as ‘Avila/Barnaby’, are infertile. Sydney has a couple of imaginary friends, a Mexican nanny, and a collection of snow globes containing black virgins. And she writes novels.

- Book 1 Title: Child of the Twilight

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $27.99 pb, 258 pp

Though she is the title character of this novel, Sydney plays little part in the action. It is a rambling story about the theft of the Bambinello, a statue of the infant Christ, from a church in Rome. It features an Australian priest who chances to be on the spot when the theft is discovered; a monastic archivist with a penchant for fabulation; an ageing art teacher; and an Australian convent-school girl with an artistic streak; a charming and strong-willed aunt and a secret lover; and an ageing art teacher. These people are among those Sydney has located ‘along the branches of the family tree of Avila/Barnaby, out to the very finest twigs. There I have found Roland the Good, Cosimo the Archivist, Diana the Manipulator, Rosita the Spinster, Corazón the Fertile, and Rufus the Virile.’

Sydney’s mother, Avila, is devout, like all the older women in the novel. Sydney herself seems to like a bet each way – or else, as a narrator, she doesn’t want to give too much away:

I am unsure what any of the people here might have really meant by all this talk of angels painting or not painting statues. Rosita seemed to take it all at face value – angels did this, statues did that; Diana, maybe half and half; Cosimo was working with metaphor a lot of the time; and Cora thought it was all stories, stories, stories and they sometimes irritated her and they sometimes made her laugh.

The fabric of this novel is made up of ‘stories, stories, stories’, linked together in various, often tenuous ways. Sydney, really an observer rather than an actor in the plot, such as it is, spends much of the time recounting tales of varying degrees of plausibility, with her own arch commentary. She plays with language and imagery, sometimes extending her wordplay further than might be thought strictly necessary:

Some quality of unreality entered the real world of paint and paintbrush and canvas and chiffon, marked the place with a splattered star, like a star advertising cheap goods in a shopping mall, or a sudden star on the tooth of a television celebrity advertising toothpaste. The moment was starred, marked for attention.

Although there are several sudden deaths, they are wreathed in romance, despite a nod towards the attendant agony for the survivors. The dominant images are of lightness – dandelions, mirrors, hot air balloons, waterlilies. Sydney needs to warn herself not to ‘get carried away by everyone’s life-story’ – the novel is full of small red herrings. Rufus’s father, a widower, has a housekeeper ‘who may one day end up marrying’ him: although it is ‘not part of this story, it’s a nice idea, and a definite possibility’. Another house-keeper is Celestina, ‘an impossibly tall, beautiful young woman from the Sudan … She is not only incredibly beautiful but exceptionally intelligent. But of course she scarcely speaks, and will keep her counsel.’ Is there any point to Celestina, other than a pleasant nod towards the charms and abilities of an immigrant minority, and an offhand acknowledgment of the labour involved in maintaining the affluent lifestyle of the upper middle class?

Early in the novel Sydney says that her grandparents used to say she was an ‘old soul’ with ‘an old head on young shoulders’. She goes on to say ‘all this is absolute nonsense’. But Child of the Twilight is written by an author who is much older than her narrator, and despite the veneer of modernity – familiarity with blogs, Facebook, and the speech patterns of Generation Y – it feels like a late novel. Carmel Bird seems to be taking a leisurely stroll in her fictional theme park, with frequent stops along the way to sit and muse at the passing parade: there is little urgency driving her plot. Without going into theories of ‘late style’, some of the characteristics associated with it – nostalgia, fragmentation, intimacy – are prominent in Child of the Twilight. Despite Sydney’s agnostic tendencies and worldly views, she is attracted to her older female relatives’ whimsical world of prayers and miracles; her story is not exactly disjointed but fairly loosely put together, and she is a chatty and easily distracted narrator. Child of the Twilight will exert its fey charm on those who don’t find its frankly pagan version of Catholicism too excessive or its continual metafictional gambits too intrusive.

Comments powered by CComment