- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

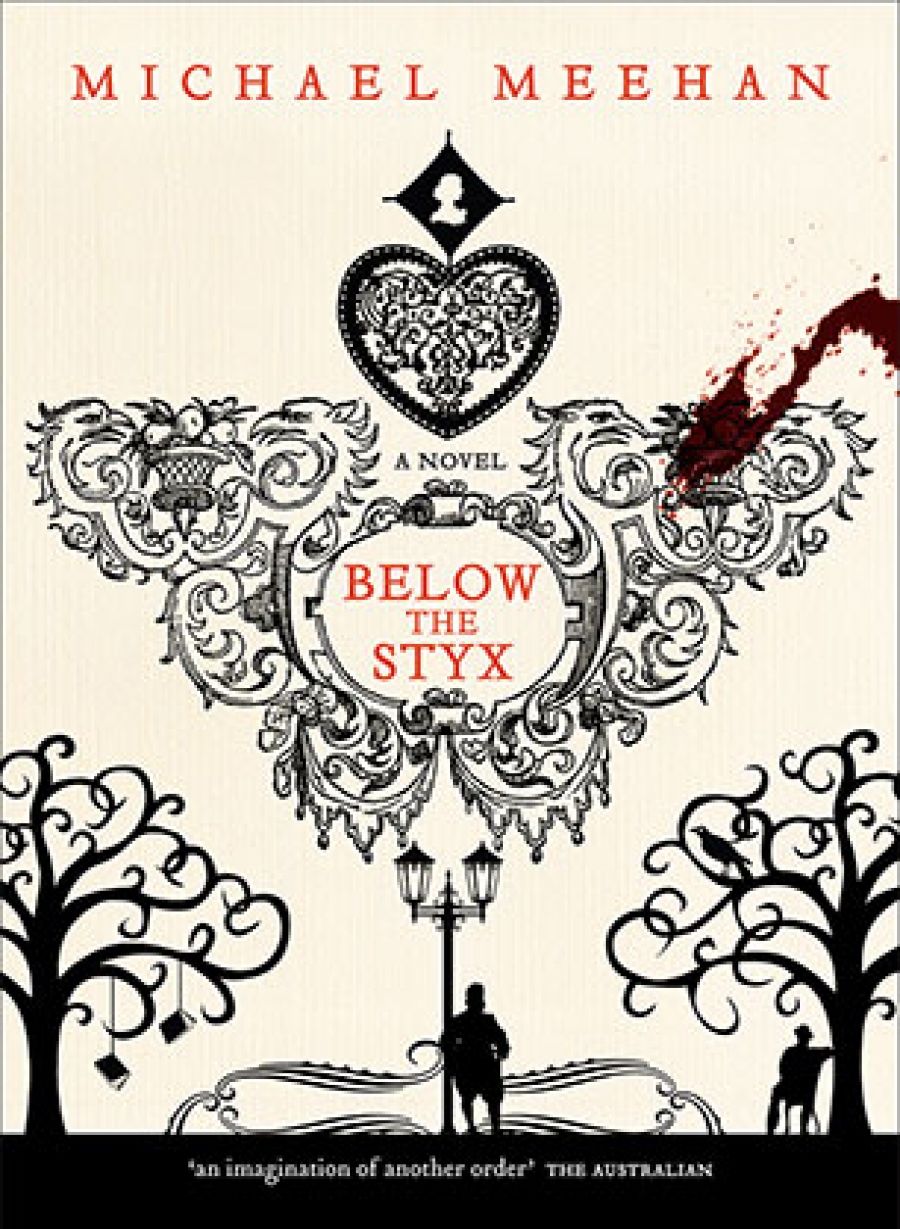

- Custom Article Title: Don Anderson reviews 'Below the Styx' by Michael Meehan

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mysteries of the epergne

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

'What’s in a name?’ as C.J. Dennis and Shakespeare asked. Maybe much, as in nomen: omen – maybe naught, as in the case of the narrator Michael Meehan’s fourth novel, Below the Styx. For this chap’s name is Martin Frobisher, a distinctive name that rings several bells. Sir Martin Frobisher (c.1535–94) was an English navigator who made three attempts from 1576 to 1578 to discover the North-West Passage, giving his name to a bay on Baffin Island and bringing back to England ‘black earth’, which was mistakenly thought to contain gold. He later served against the Spanish Armada and raided Spanish treasure ships.

Meehan’s protagonist would appear to have nothing whatsoever in common with his Tudor namesake, and his name may be a subspecies of that great Australian comic trope, the furphy. From the first page of the book, it is all but impossible to shake the conviction that ‘Martin Frobisher’ has a weighty significance, while it may in fact be empty, a linguistic terra nullius. It may be a Shaggy Dog, happily at home in this benignly witty and whimsical novel, which is also a murder mystery.

- Book 1 Title: Below the Styx

- Book 1 Subtitle: A novel

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin $29.99 pb, 277 pp

Indeed, so difficult is it to be certain just what kind of beast Below the Styx may be that one is tempted to do a Northrop Frye and dub it ‘an anatomy’, or its antipodean cousin, a bunyip. It is part novel, part murder mystery, possibly a cod-murder mystery, and part, a large part, a counterpoint or interstitial text generated by the fictional Frobisher and the historical Marcus Clarke. For Martin Frobisher is obsessed by the life and times of Clarke, and Michael Meehan has done extensive and documented research into For the Term of His Natural Life and Clarke’s misfortunes by way of the scholarly labours of Brian Elliott, Stephen Murray-Smith, Laurie Hergenhan, Ken Stewart, Michael Wilding, and Wendy Abbott-Young. Yet, it must be insisted, Below the Styx wears its learning lightly, if not playfully.

Now, about that murder. Surely reviewer’s rules are not infringed by discussing a murder that occurs on the first page of the book and is admitted by the narrator-perpetrator. His wife having called him a ‘louse’, the ultimate insult in his family, Frobisher dispatches her with a blow from an epergne. He seems more interested in describing his weapon than in checking whether the odious Coralie is in fact dead.

What is an epergne? I hear you ask. If you had asked my father-in-law, Ernie, in happier days, he would have taken you aside, tears of gratitude welling in his eyes, and lectured you at fond and foolish length on the history of the epergne, its classical origins, its imperial antecedents, the growth of the native industry, the place of epergne design in the evolution of Australian decorative arts, the gradual use of native insignia, the sorry decline in the art of the epergne in the century of the common man. The epergne is, in short, a large, unwieldy object designed to suspend delicacies – usually fruit – above the table. Equipped with a column (Doric, Ionian, Corinthian), it has a modest footprint, as I believe the computer people say, making table space available for other forms of clutter … I struck her. My hand reached for the nearest blunt object, and closed around the pylon.

Meehan is so enamoured of the ‘epergne’ that he speaks of it in propria persona in his acknowledgments. ‘There are some large colonial epergnes on display in the Art Gallery of South Australia. For those who live in Melbourne, there is a fine example of an epergne, complete with native insignia, propped up on the counter of Gerald’s Bar in Rathdowne Street. It is firmly attached to the bar, and is not available for wielding by customers.’

The tone in both quotations is antic, and characteristic of Below the Styx throughout. Perhaps Frobisher shares an antic disposition with Clarke, as well as sharing a predisposition for falling in love with his sister-in-law. For all Clarke’s enduring fame as a chronicler of the ‘weird melancholy’ of the Australian Bush, and his ‘imprisonment’ in the composition of For the Term of His Natural Life, Frobisher and Meehan do not let us forget Clarke the journalist, the man-about-Melbourne Town, the wag and the wit. ‘I usually make my opera a whet to my oyster. The music, the lights, the sparkling eyes, the glancing ankles, the palpitation of a thousand budding bosoms, all these refine the mind, and elevate the soul to concert oyster pitch. Sir Walter Scott, when a young man, ate oysters by the barrel.’ (Nine lines of learned examples follow.)

Frobisher characterises his account of Clarke as ‘the sludgey Frobisher inward-probing mode’, in contrast with that of his research assistant, Petra, a postgraduate history student who practises ‘Who Did What to Whom’, and visits him in the remand centre with the fruits of her research. While Frobisher himself has in no way enjoyed a ‘brilliant career’, he is dedicated to giving Clarke his due. It’s just that the connections between Clarke and himself may be illusory, projections of that ‘inward-probing mode’. In a not completely clear way, to this reader at least, Frobisher and the epergne may not be responsible for Coralie’s death. There is a mysterious pillow, and a mysterious hand attached to it.

Comments powered by CComment