- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Bruce Beresford has left a greater imprint on the national sensibility than most people might think. From The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972) through The Getting of Wisdom (1977) and Breaker Morant (1980), he has demonstrated a virtuoso ability to dramatise Australianness, classic and modern. His films Don’s Party (1976) and The Club (1980) mean that we are never likely to forget the idiom in which David Williamson first represented us, because Beresford has made it part of the cinematic argot of the country; a new production of a play is automatically measured by how much the actors stand up to the classic performances of Graeme Kennedy or Ray Barrett or John Hargreaves in Beresford’s vision of the plays.

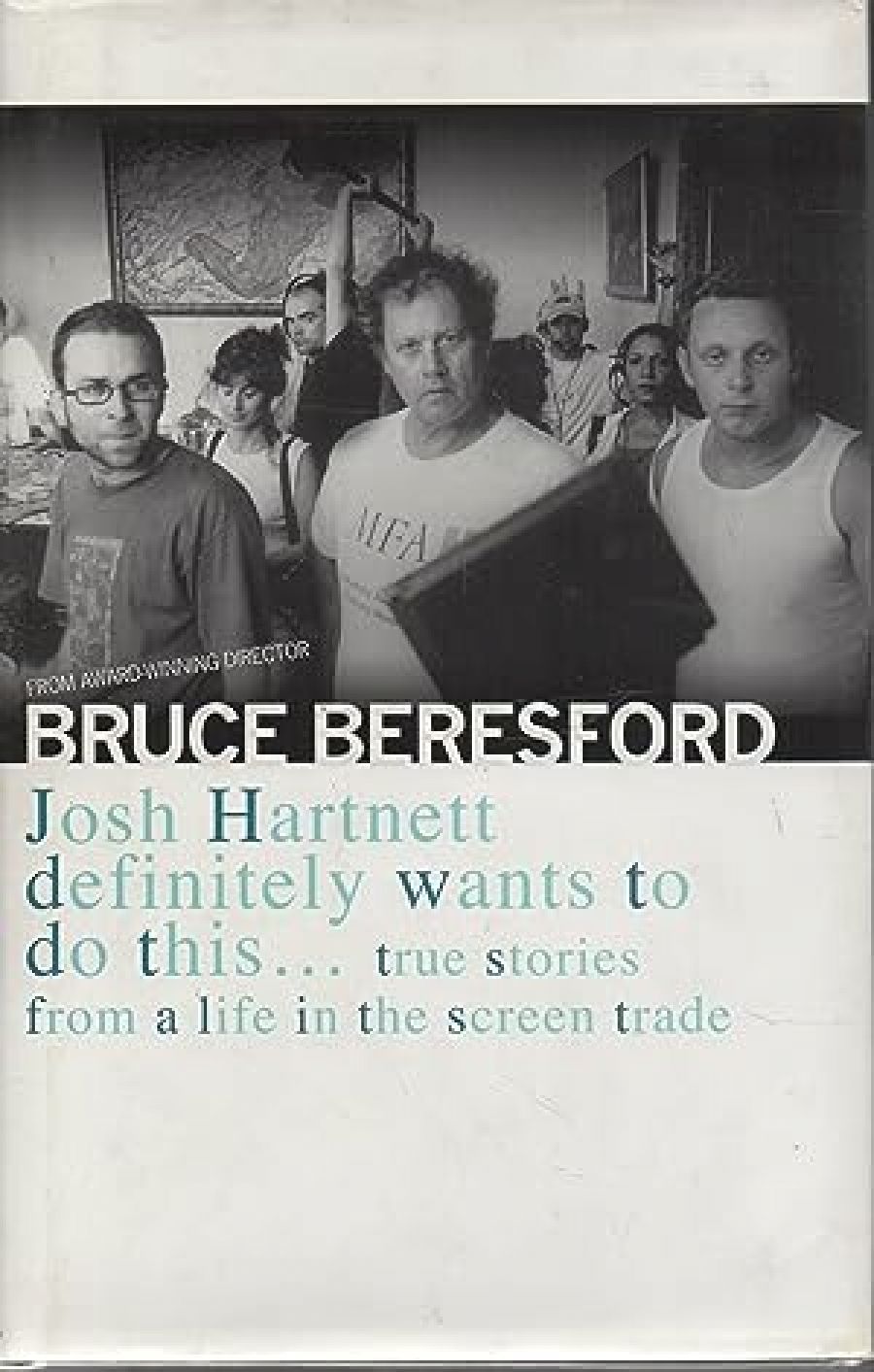

- Book 1 Title: Josh Hartnett Definitely Wants to Do This

- Book 1 Subtitle: True stories from a life in the screen trade

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $39.95 hb, 322 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

One suspects that Beresford has suffered in the general estimate because, unlike Peter Weir and Fred Schepisi, he did not begin film-making life as an auteur: there wasn’t the sense of mysterious worlds lurking like a pied piper’s doom inside this one, nor the blight and tumult of a Catholic childhood. He has never made a Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) or a Devil’s Playground (1976), and his lack of an obsessive personal vision has dovetailed with his versatility, the way he accepts the role of the jobbing director who can film Brian Moore’s The Black Robe (1991) but who also hung out to make both Miss Potter (eventually made by Chris Noonan in 2006) and the biopic about William Wilberforce that Michael Apted filmed as Amazing Grace (2006). Beresford’s versatility is not separate from breadth of vision and an omnicompetence that make him more like an upper-level stage director than he is like the hack or visionaries of the film industry.

Recently, we have had Beresford’ production of André Previn’s opera of A Streetcar named Desire at the Sydney Opera House. Year ago, I saw his production of Richard Strauss’s Elektra and was stunned by the brilliance of the production and by its truth to the brutalism and power of the Strauss-Hofmannsthal vision. The hysteria was terrifying; you could almost smell the blood. It made me think what a theatre we might have had if this man had not spent most of his life fiddling with cameras.

Josh Hartnett Definitely Wants to Do This is a selection of Beresford’s diaries from late 2003 to mid 2005s. It is a charming, unabashed, slap-it-down-on-the-page beguilement of a book, impeccably phrased and showing a quite disarming perfect pitch in Beresford as a writer. This comes as a surprise, but it shouldn’t. Beresford is a friend of Barry Humphries, who states in the cover blurb that the director writes as well as he talks. Beresford also likes to try his hand at scripts. In recent years, he has been hawking around a script of Henry Handel Richardson’s The Fortune of Richard Mahony (1917-29), which, incredibly no one is willing to produce. It really is a case of poor fellow, our country, when you add this to the scandalous fact that the trilogy is out of print at the moment. You would think that art form might assist art form and that someone of Beresford’s eminence might tempt entrepreneurs or funding bodes – but no.

Beresford is funny about this sort of thing, though it is clearly a sorrow to him. What can he be expected to do in a world where Hollywood producers tell him he should think of a less silly name for a place than Singapore or ask why he wants to make a film about this nonentity Mahler?

This is a book about how an intensely intelligent, humorous and likeable-sounding man makes his way through the world in his later sixties, attempting to do what he thinks best, which is to make films. He seems to work like a dog, constantly reading and rewriting scripts and talking to all manner of money-men, some of whom mysteriously lie to him about the conversations they have or have not had with their fellows. There is a kind of running gag in Josh Hartnett whereby one of two of Beresford’s crucial associates is clearly lying his head off, but Beresford can’t work out which one.

What emerges from these pages is a candid, unselfconscious portrait of a man bursting with an energy to create but also full of worldly patience with the difficulty of the film-making game, and one who is willing to do all arts of hackwork in order to keep his hand in. He ends up making, in Bulgaria of all places, a thriller with John Cusack and Morgan Freeman called The Contract (the plot of which he thinks is silly) when he would much prefer to do the Wilberforce film. He can’t believe that no one has ever done it before.

This a disarming account of the world of film by an unusually cultivated man who has wanted to make films since he was five years old but is also interested in other cultural forms. He adores classical music, for instance, and never forgets the story of Dvorak hearing an unknown beating away at a piano inside a house he was walking past, only to discover that it was Janacek. Beresford sees Brian Dennehy in Death of a Salesman and is filled with wonder at (an unnamed) Trevor Nunn’s computatronic effects in his production of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Woman in White (with characteristic frankness, Beresford says he must try it himself next time he does an opera).

One of the reasons why readers will delight in these diaries is precisely their frankness. It is typical of this book that it should be named after a youngish and monumentally self-absorbed star (the lad who had such an erotic spring in his step when he appeared in Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides [1999]), and that the book concludes with the news that he will only make the film if Beresford does not direct it. Beresford has plenty to say about how actors rarely say no to projects (they just let them die) and how they are fragile creatures because they tend to have beauty rather than talent.

On the other hand, he is full of admiration for, say, the Ben Kingsleys of this world. And he is fair, suggesting as he does that many of the big stars owe their positions to the fact that they are good to work with. It does not so much madden as bemuse him, however, that every film must have a star of the moment and that the most obviously filmable projects won’t get up without them.

Beresford is very taken with a script by Jeffery Archer about the explorer Mallory, who died in the attempt to climb Everest in the 1930s (very young, he set off in walking tweeds). Archer, whom Beresford likes, and the director have a good time at the Ivy – Beresford notes that people still call him Lord Archer, despite the stint in gaol – but so far the project has come to nothing. No Jude Law, no Paul Bellany, no money.

Josh Hartnett can be read as one long lament of a film-maker, as well as an engaging advertisement for a director seeking work. One can only hope that the minnows and warlords of the film industry, here and elsewhere, sit up. Beresford clearly a powerhouse. We read how he devoured the whole of Hugo’s Les Misérables in two days when there was talk of his directing a film of the musical. He resolves to do the same thing with a huge thriller that Dino De Laurentis has translated just so that Beresford can contemplate the film he might make of it. He likes De Laurentis because he admires people who are willing to trust his capacity for artistic control.

This book is, in its quiet, articulate way, a wonderfully cold-eyed account of the professional director’s life and the way in which talented people have to devote three quarters of their lives to getting the work they were born to do. Along the way, it is full of a thousand casually expressed opinions. Beresford is concerned that even the best directors rarely do anything after the age of fifty-five. He worries about the fact that most directors (at best) only make five great films, and takes heart in the fact that Bergman made at least twenty.

Sometimes he seems palpably wrong. He thinks everything David Williamson has written is of a uniformly high standard. He thinks that Von Sternberg did his bit to ruin Marlene Dietrich’s talent. (I was always taught, and continue to believe, that it was pre-eminently with the director of The Blue Angel [1930] and The Scarlet Empress [1934] that Dietrich was a great actress.) But it doesn’t matter. There is something very refreshing about the confidence with which Beresford is willing to let his casual opinions sit on the page.

There are comments about the son who translates Plato for Penguin Classics, the daughter who makes films, about Barry Humphries and Jeffrey Smart and Bruce Beresford’s continuing – and so far vain – attempt to film David Malouf’s Conversations at Curlow Creek (1996), and the script of it that he has been working on.

The man is some kind of national treasure, and every word he writes crackles with reality and truth. Josh Hartnett is a monument to a particular kind of Australian cultural omnivorousness as well as to Australian wryness and self-deprecation.

Bruce Beresford is not, of course, an expatriate celebrity in the Germaine Greer mode. He says he has only been recognised by strangers three times in his life. He is simply a distinguished film-maker who is too interested in what he is doing to make a career of watching himself and being watched. But he is, almost offhandedly, a supple writer. Everyone should have a look at this book.

Comments powered by CComment