- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Omar Nassif and Enzo Cugliari are fringe-dwellers, beyond ‘white trash’. That harshest of middle-class put-downs fairly locates their distance from the outsider types who claim our interest. Omar and Enzo are anti-charismatic, their physical selves undescribed. In contrast, Ari, the angry child of migrants in Christos Tsiolkas’s Loaded (1995) wants drugs, sex and dancing, and inevitably his character now conjures up the sex god in the film role, Alex Dimitriades. On the top shelf there is Lord Lucan, incognito and surgically disenhanced, slumming on Tasmania’s coastal glory in Heather Rose’s The Butterfly Man (2005); attractively guilt-wracked and evolved, Lucan trails glamour and enigmatic women. The actor would be Jeremy Irons.

- Book 1 Title: Omar and Enzo in the Big Talking Book

- Book 1 Biblio: Clouds of Magellan Publishing, $24.95 pb, 190 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Omar Nassif and Enzo Cugliari have a relationship. (At no time, except in official dealings, do their family names arise – their single name status marks them as nonentities, at ironic opposites to the mega celebrity of Madonna and Bono.) They live together and share the same bed. Omar makes coffee for Enzo. Their milieu is unwashed, illiterate and on the bleeding edge of violence. Their way of living might be called survival.

Omar is a waiter and cleaner in a ratty restaurant. Enzo answers the phone as Tony: his advertisement reads ‘Continental, top and bottom. Hung, hourly rates.’ Omar steals cutlery and money out of aggravated boredom. Tony turns his tricks spaced out on speed. But they are not ‘gay’. As Enzo says to the man who will become his pimp/mentor, ‘I’m not a cocksucking homo. I don’t fucking do that.’

Omar dreams of doing nothing, as in a scene from a stolen postcard of the Amalfi coast. Enzo drifts along, head full of popdocos on reincarnation, and Native Americans and Vikings, with their lives of rituals and rules. Omar and Enzo are as rudderless as the people they know – the impressively sleazy hustler Clifford Askey, who winds up in a hospital bed; his ‘girlfriend’ Audrey Patch, grasping at New Age straws. Omar and Enzo have no history, and the present barely holds any significance. ‘Omar knew that for Enzo, “now” didn’t mean much. He’d been here before and he was going to come back, so “now’’ was never real.’ In a curious way, Omar and Enzo are the least differentiated of the characters; they might be splinter halves of an ego.

So far, so grim. But the grit has grip. Each moment is precisely lit, as cinematic as the language is economical. One of Enzo’s ‘clients’ is a shoe salesman who gives an epic recital of early sexual arousal: his father, in an imitation of the Saviour’s sacrifice, strips off his shirt and exhorts his son, the future salesman, to whip him for one of the son’s misdemeanours.

The vignette that leads nowhere, but illumines its world, is a device perfected in recent crime fiction. But only a rare crime thriller delivers the sudden weight that comes during this book’s climatic frenzy when, untethered from sense and morality, one of the characters takes a life. It is a perfectly inarticulate moment – he doesn’t know why he is doing it, his victim is taken unawares. A house and consciousness go up in flames.

In a police interview, the killer justifies himself: ‘He sort of fell on the floor. I cut him. I panicked. He was gonna rape me.’ The episode is supposedly based on a murder in Victoria in 1992 that led to the notorious ‘homosexual advance defence’. It provides the unstable pivot of the story, specifying only the obvious but implying everything, and somehow – in a slow release – comprehending the homophobia and sexual self-loathing. At the end of the book, Omar, who is violently cut and bashed in a karmic retribution, finds himself by a pier – or doesn’t quite find himself, though he does locate a feeling.

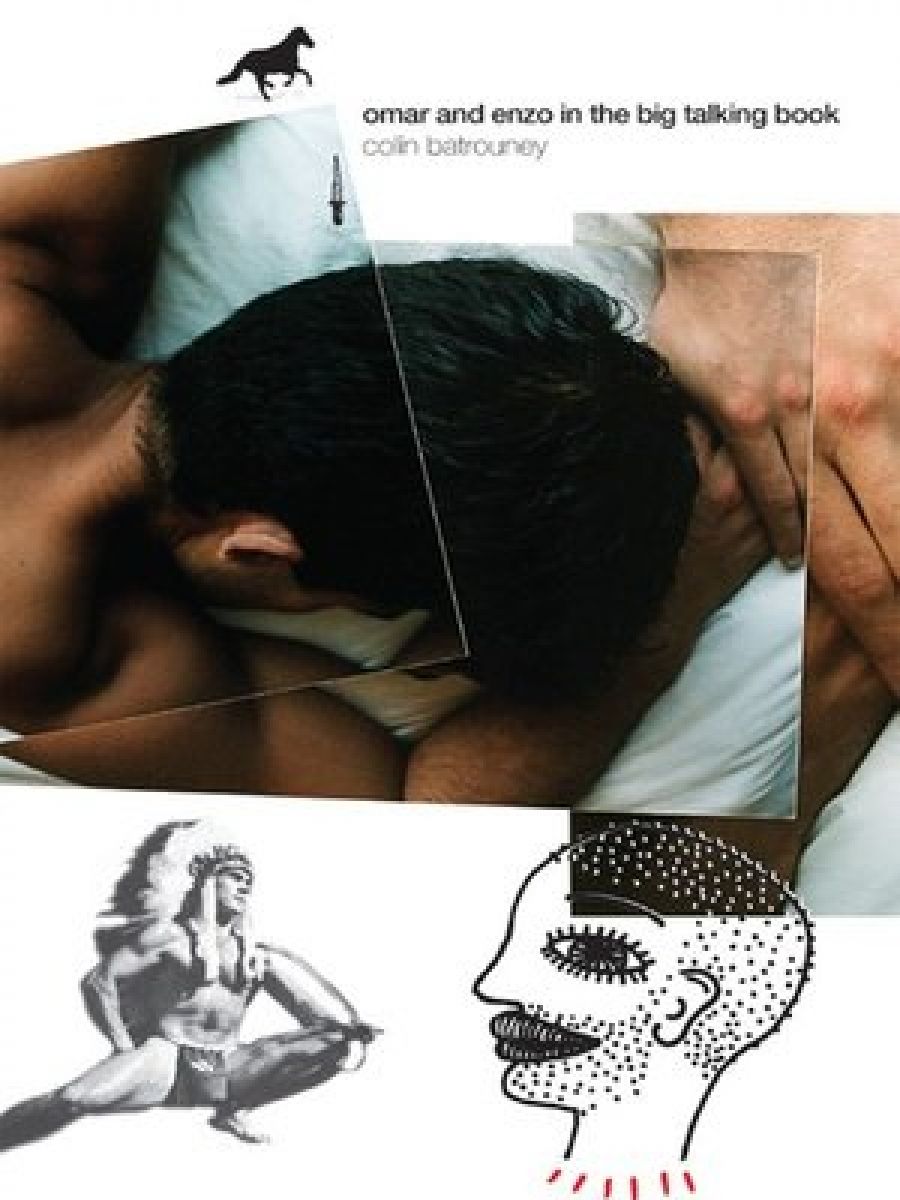

I still don’t understand the title, or the lyrical prologue and epilogue (picture a beach scene by Charles Conder for the former, and a deathbed scene by Tom Roberts for the latter), but the cover art is by the multi-talented Batrouney. It is no surprise to discover that he is an exhibiting photographer - he clearly has an eye. And this brief, confronting book also recommends his ear, mind and heart.

Comments powered by CComment