- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Marginal and Mainstream

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Cinema of Australia and New Zealand is the thirteenth of Wallflower Press’s ‘24 frames’ series, but there is no need for the editors to feel superstitious on that account. This is a series which presents certain problems. It requires the editor(s) of each volume to choose twenty-four films that are, in some degree, representative of the titular country, or, as the case sometimes even more dauntingly is, of two titular countries – and I know whereof I speak. Having edited Wallflower’s The Cinema of Britain and Ireland (2005), I can sympathise with the difficulties involved in trying to achieve any sort of representativeness across not one but two film-making countries. And I might add resentfully that Canada gets a whole volume to itself. Canada!

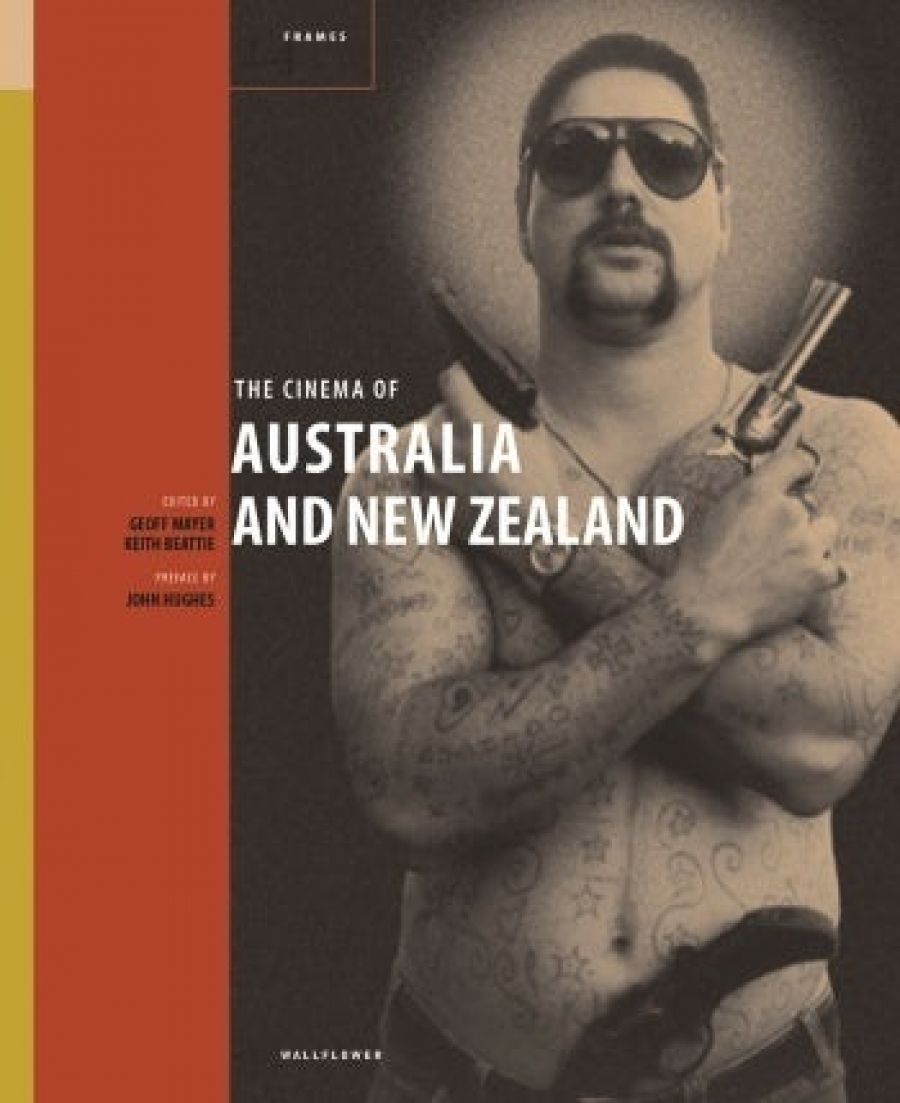

- Book 1 Title: The Cinema of Australia and New Zealand

- Book 1 Biblio: Wallflower Press $49.95 pb, 259 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Wallflower has been fortunate in having as editors Geoff Mayer and Keith Beattie, two academics who have taught film in both Australia and New Zealand, and who may be supposed to have some grasp, theoretical and empirical, of the film industries of the two countries. They have been venturesome in their choice of films, brave even. avoiding for the most part the obvious titles – there is, for instance, no chapter on Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) or Sunday Too Far Away (1975). For some readers, a few of the titles highlighted may seem too unfamiliar, and, from a commercial point of view, too obdurately non-mainstream.

That said, one can have little but praise for the range the editors have encompassed within the parameters of the series. Historically, the book takes in the silent days, almost from the beginning, to Rabbit-Proof Fence in 2002. The editors’ introduction offers an appropriate and, especially for overseas readers, useful synoptic view of the century in film as it obtained in both countries. This introduction works well in laying a broad chronological context in which to situate the chosen films, drawing attention. for instance, to the increasing globalisation of the film industry and to the balancing act whereby ‘directors have been able to fashion a distinctive place somewhere between the “poetic realism” of the European art film and the narrative demands of the classical Hollywood cinema’. Many of the individual essays articulate in detail this viable compromise.

In generic terms, the selected films embrace documentary as well as fiction filmmaking and even include one made for television. Again and again, one is struck by the genre hybridity exhibited by the films. In Mayer’s own chapter on Lee Robinson’s The Phantom Stockman (1953), one of the few films that kept the idea of feature film-making alive in Australia in the postwar years, it is presented as a variant on the western genre in ‘exotic’ settings. (Mayer also draws attention to the lack of government interest in a local film industry.) In discussing the even rarer New Zealand film, John O’Shea’s Runaway (1964), Hester Joyce identifies

the characteristics of the chase movie not merely in a distinctive setting but as also influenced by British film noir, and Wendy Haslem’s delineation of the rites-of-passage tale crossed with the road movie and ‘Australian/Asian art cinema in Clara Law’s The Goddess of 1967 (2000) persuades me that I need to seek out this complex- and subtlesounding work.

Particularly impressive is the substantial coverage allotted to films, from both countries, which focus on their indigenous populations. Sometimes, as in the case of Two Laws (1981), it is the product of Aboriginal and white filmmakers in collaboration, and (in Beattie’s lucidly argued piece) offering both a strongly polemical stance in relation to its subject matter and a ‘radical revision of filmmaking practices’. On other occasions, it is a matter of white filmmakers addressing social and political injustices to which indigenous populations have been subject, as in the post-colonial accounts of Charles Chauvel’s Jedda (1955), by Barbara Creed, or of Jane Campion’s The Piano (1933), by Rochelle Simmons.

As well, in several other essays, such as Joyce’s rather plot-heavy dealings with Lee Tamahori’s Once Were Warriors (1994), Ingo Petzke’s chronicling of the production history and media responses to Phillip Noyce's Rabbit-Proof Fence (somewhat short on textual analysis) and Peter Hughes’s astute reading of John Hughes’s critically neglected documentary, After Mabo (1997), the editors show their concern for this matter.

As well as attending to generic contexts and sociopolitical determinants, the authors seem to be operating within guidelines that ask them to go beyond just close reading of individual films, and to offer revealing insights into the production circumstances in which the films were set up. Without the volume’s adopting an unsustainable auteurist stance, the writers have been at pains to place a particular film in the context of the director’s work at large, as in William D. Routt’s affectionate account of Ken Hall’s rural comedy Dad and Dave Come to Town (1938), a well-chosen title to epitomise the prolific 1930s and one of its most prolific exponents, or in Rose Lucas's clear-headed intertextualising of Gillian Armstrong's 1997 adaptation of Peter Carey's Oscar and Lucinda (1988). As a result of such stress on context as well as on text, the book as a whole acquires some sense of survey, at least of the feel of more wide-ranging activity than a mere twenty-four titles might have suggested.

If the book deserves respect for seeking out comparatively obscure titles from the two countries, it also does well by some big names. It was inevitable that there would be a chapter on The Lord of the Rings (2001, 2002 and 2003), and, though one might quibble over the extent to which it is usefully considered as an auteuristic work from Peter Jackson, or whether Laurence Simmons really comes to terms with ‘the complex issues of adaptation’, he does admirably with the film’s ‘dizzying digital effects’. And Phillip Bell’s celebration of Moulin Rouge (2001) as ‘a new kind of movie, one that fully exploits the technologies of production and of distribution afforded by the digital age’ is a sophisticated consideration of the ‘audiovisual, theatrical and cinematic experiences [his italics]’ the film offers. These two films point to the increasingly global nature of filmmaking, so that it would be more accurate to add ‘USA’ to the statement of nationality at the top of the chapter on each, in the way that The Piano is labelled ‘Australia/New Zealand’. Speaking of ‘big names’, one is also reminded that these do not necessarily apply only to blockbuster fictions: is there an Australian of mature years who hasn’t heard of John Heyer’s documentary, The Back of Beyond (1954), whose local and international influences are confidently limned by Deane Williams?

Of course, the quality of the essays will vary when there are twenty-four contributors, but overall it is remarkably well sustained. The book begins with two shapely and eloquent studies of silent film fragments (The Story of the Kelly Gang [1906] and The Woman Suffers [1918]) from Ina Bertrand: it goes on intelligently to make one rethink films such as Michael Powell’s They’re a Weird Mob (1966), in Adrian Danks and Rolando Caputo’s essay, and Peter Weir’s The Year of living Dangerously (1982), in Felicity Collins’s perceptive account of mixed messages and genres; and it has room for notable oddities such as Corinne Cantrell's autobiographical photo-essay, In This Life’s Body (1984) and Len Lye’s four-minute experiment with ‘camera-less animation’, Free Radicals (1958).

You can’t do everything in this sort of collection. Mayer and Beattie, in this case, have ensured that expertise and eclecticism jostle productively, offering new insights into films both, in industry terms, marginal and mainstream.

Comments powered by CComment