- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Selective Pruning

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Joanna Mendelssohn is best known as an art critic and historian. After the publication of an essay in The Griffith review entitled ‘Going Private’, Pluto Press commissioned her to write a piece for its Now Australia series. Similar to Black Inc.’s Quarterly Essays, but even more determinedly non-academic, the Pluto Press format is part of a publishing phenomenon and covers a range of political, intellectual and cultural views on public issues and debates. The authors are not necessarily experts in the area they write about, nor are their views always based on systematic, in-depth research.

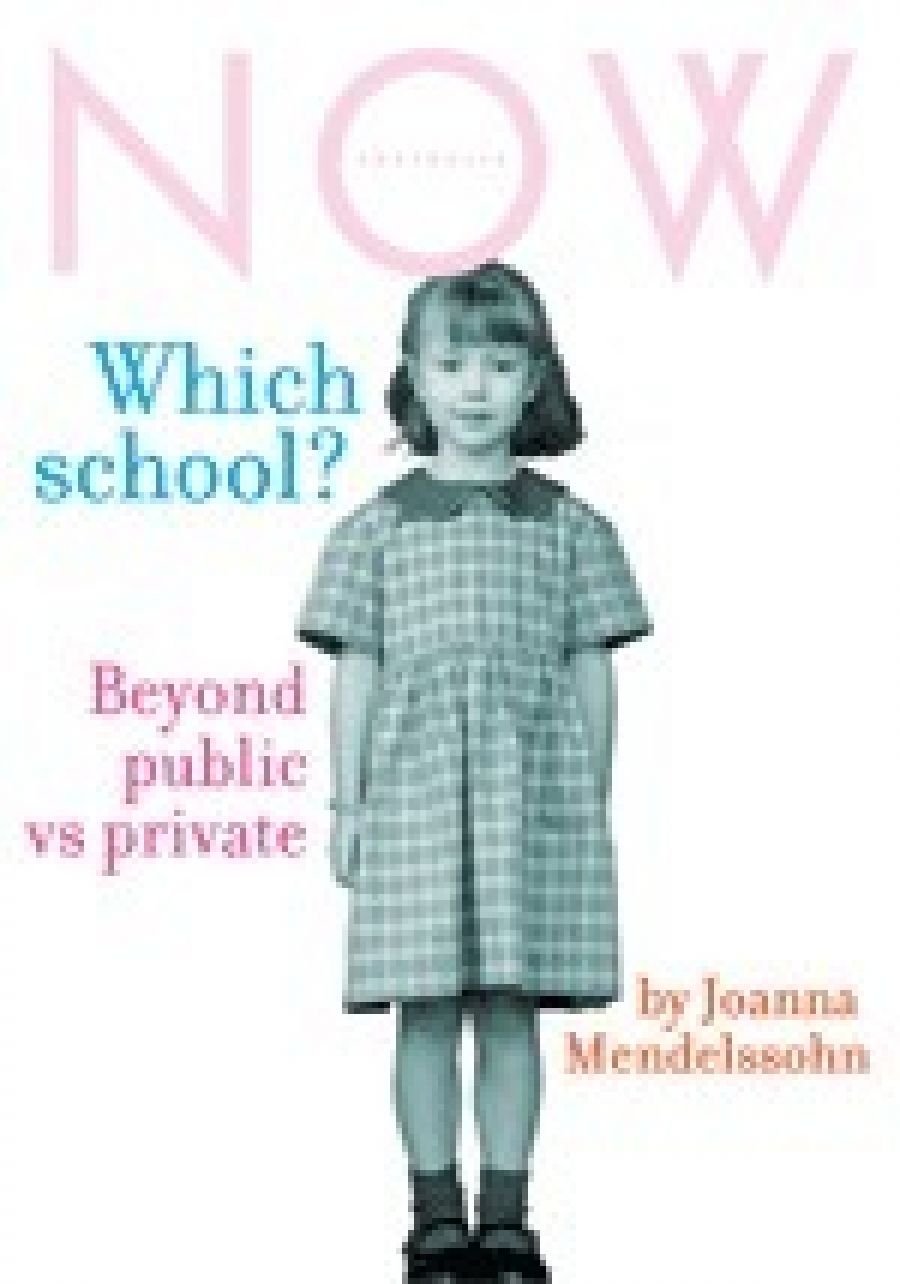

- Book 1 Title: Which School?

- Book 1 Subtitle: Beyond public vs private

- Book 1 Biblio: Pluto Press, $17.95 pb, 108 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In Which School?, Mendelssohn asks why parents like herself, who were happy with their own state school education, are choosing private schools for their children. Have parents changed or have schools? What happened to the excellent state school education she encountered in the 1960s? To explore these questions and others, the author draws upon her own experience as a parent facing the dilemma of deciding which school to choose, as well as on conversations with principals, teachers, parents and students from public and private, selective and religious schools.

Her conclusions reflect some of the most respected thinking in education. Parents who have the luxury of choice should make their decision based on the needs of the individual child. If the school offers a broad curriculum, monitors students’ needs and progress, displays a positive disciplinary climate and focuses on the students’ enjoyment of learning, then it is worth considering. Mendelssohn emphasises the value of early childhood education and the need to acknowledge teachers’ social worth by rewarding them with higher salaries and greater social status. Although she avoids saying definitively which system is best, her strong criticism of the public sector reads as an endorsement of private schools.

The kinds of problems that Mendelssohn identifies in public schools are burnt-out teachers, oppressive, centralised administrative structures and a national union that she believes defends the incompetent. She experienced the fallout from such problems when her own children were in the public sector, prompting her to move some of them to private schools once she could afford the fees.

Individuals, writes Mendelssohn, are pivotal to the success or failure of a school. The schools with the creative teachers and principals who allow them to exercise these qualities are the ones parents should seek out. To illustrate her argument, Mendelssohn describes her own school experience in the 1960S. The key to the success of her final two years in the local comprehensive was a few inspiring teachers. She also tells the stories of St Andrew’s, a private school in Sydney, and Elizabeth Vale Public School, located in a disadvantaged area of South Australia, where the principals have been responsible for the schools’ success. While the private school continues to thrive, the public school’s development was at least temporarily thwarted when the state education department terminated the principal’s appointment, notwithstanding outstanding results. Mendelssohn characterises this unpopular decision as the kind of mistake that remote bureaucracies can make to the detriment of a school community.

Mendelssohn sustains the metaphor of education as a garden throughout the book. Just as a garden needs to be nurtured well ahead of time for maximum enjoyment, so too, she argues, is educational policy organic. Successive governments from the 1950s to the 1970s invested in education: prosperity was the result. However, in recent years, ‘the education garden has only been selectively watered and fertilised, and only some plants have been pruned’. By the end of the book, Mendelssohn has reduced the issue of which school to ‘a horticultural question’ and asks: ‘How is it possible to make our children’s gardens grow? How can we make sure that our infant potatoes have as much chance to flourish as the passionfruit and the grevilleas?’ The metaphor, initially evocative, begins to pall.

Mendelssohn is least convincing when she proposes that it is time to move beyond the public versus private debates about education, as if the issues were no longer relevant. When we ask what's gone wrong with public schools, we can't avoid the fact that one of the Howard government's key educational policies has been to engineer a shift from public to private provision of education. More than a third of all children are now enrolled in private schools. Whenever Howard or his ministers talk about a crisis in education. it is code for a crisis in public education. Their strategy of debasing the image of public schooling has already had profound effects and will continue to do so for years to come, even if there is a change of government in the imminent election.

In some ways, the book is New South Wales-centric. Mendelssohn hates centralised bureaucracies and selective schools, which are defining characteristics of New South Wales, but less so of other states, particularly Victoria, where there has been a devolution of power over the last decade and far fewer selective schools. There is still accountability to the state in Victoria, but principals have greater autonomy and are responsible for hiring staff and budgets.

But these remarks are not meant as criticisms – more as an indication of my engagement with her arguments. Mendelssohn’s essay is provocative, with a strong narrative line. Moreover, it is wonderful to see education as a topic in Pluto’s Now Australia series: too often education is overlooked in such publications, despite its social and cultural significance. The hope is that this is the first of many focusing on issues and debates in education.

Comments powered by CComment