- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On the stage or off, Peter Mavromatis is the unswerving centre of these stories. Unswerving as a focus, that is – in himself he swerves all over the place. Who and what is Peter Mavromatis? That’s what he’d like to know. His Cypriot parents and grandmother know who he should be. Sydney-born, he has grown up saddled with Greekness as a birthright and an unpayable debt. Peter Blackaeye: is he ‘Grik’? No, the Greeks at GMH decide, and drive him off the job. Australian? Not to his family, nor to many Australians.

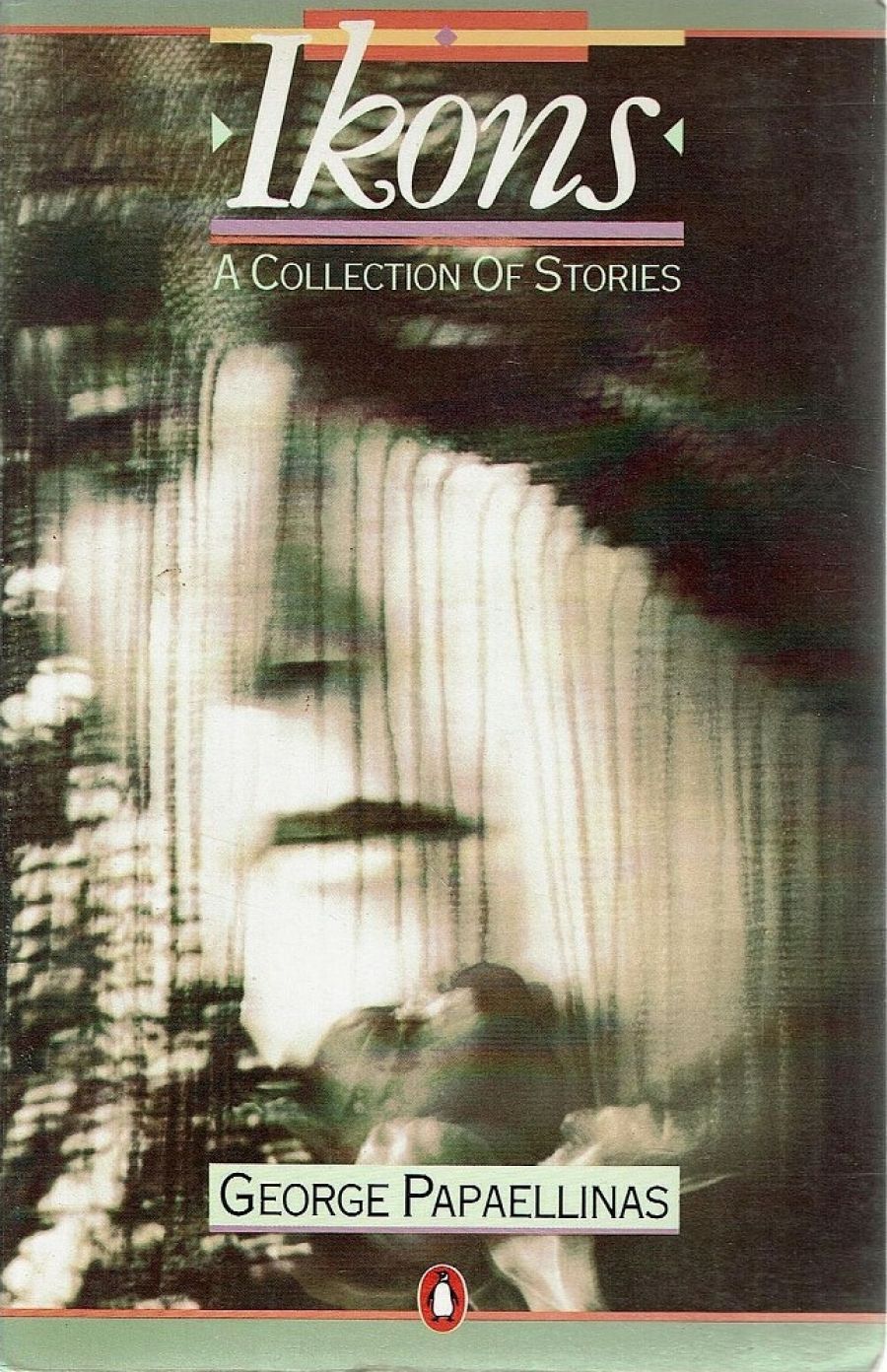

- Book 1 Title: Ikons

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, 198 p, $5.95 pb

If this sounds as if he can be obnoxious, all who love him would agree: (‘Cut the crap, will you, Pete.’) Just the same, he makes you care intensely, in the maddening way of Saul Bellow’s Herzog, for example. And this goes for the parents too, in the stories about them.

From the start we watch him groaning under his burden of conflicting loyalties, yelling at his grandmother, sulking with his parents. In one fine, dense story ‘Into a Further Dimension’ – he wins the prize for Greek at school, but Ancient Greek, (‘We wanted you to do Greek because you’re Greek and that’s not Greek,’ protests his mother.) Mr (‘Call me Roger’) Stimpson thinks modern Greek culture is degenerate. Peter’s parents come to the prize-giving: his father, of course, will disgrace him …

To their despair, Peter soon gives up his course to embrace the working class. In ‘Around the Crate’, the first of two strong and bitter factory stories, the gang of rough Greeks at GMH become his protectors at first, then his tormentors: the old Greek in charge tries to help him handle them, but Peter won’t be told. Later, in ‘Christos Mavromatis is a Welder’, Peter’s father is retrenched after thirty odd years. His life is over and what has he to show for it? Only Peter: ‘that smartarse, that talker … That trophy.’

Before that, in ‘Peter’s Song’, Turkey has invaded Cyprus. To Peter’s astonished disgust, his father is distraught and gets blind drunk, and in no time so does Peter: ‘I got sucked into all that shit’. His father ends up wading into a Turkish cafe somewhere in Sydney, fists flying … The story fades on Peter still doggedly explaining.

As story follows story, such a richness of detail has accumulated that the writing can risk being elliptical, even over-charged. ‘Peter Mavromatis Rides the Tail of the Donkey’ comes off magnificently. He is on an island (Santorini?) – he never makes it to Cyprus – and so caught up in the drama of the self that he is blind to the reality around him. He can’t do a thing right, whereas his girlfriend, Stella, who is Australian, fits in smoothly with things as they are. She and Peter quarrel a lot. He fumes and baulks and pontificates. His every attempt to connect with Greeks enrages them: just as in the Junta’s torture compound in Athens, he had to desecrate a prisoner’s bed by lying on it like any brash tourist, but in tears: ‘the people suffered’.

‘“But not you!”’ (Stella, appalled.)

‘No, but his people!’

The climax is swift and brutal. He is put to a last test and, not being a saint, fails it. The outsider, outcast, flies home alone to Sydney. But he has his photos! And vindication might yet come out of that black eye, the camera lens.

In ‘In Which Peter Mavromatis Lives up to his Name’, his people are mounted on the gallery walls. His parents come to the opening. (‘And here’s the fruit of their labour, a right plum this one, just bursting with sap and a pride in his doings.) He catches sight of one black-and-white glare, suddenly that of his dead grandmother, who held him squirming and giggling on her lap and showed him his grandfather’s photo: ‘Petro, do not forget from whom you are sprung …’ He has come full circle.

He ends this night sopping in a gutter with – yes, a black eye, but he’s set to prosper. He’s in the place for it, the land of the smugly unscrupulous – Australia doesn’t get off lightly either.

These stories have a lot to say and say it in a torrent of words that keeps you paddling hard, so you don’t go under. Sometimes you do, but the manic verve carries you on. Sometimes syntax fractures under the pressure, phrase piles on phrase – which is not to say the writing is self-indulgent. It is rigorous, with much skilful juggling with point-of-view to make cross-references multiply and ironies stand sharply out. You don’t need to be multi-cultural, or Australian either, for this book – human will do.

Comments powered by CComment