- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

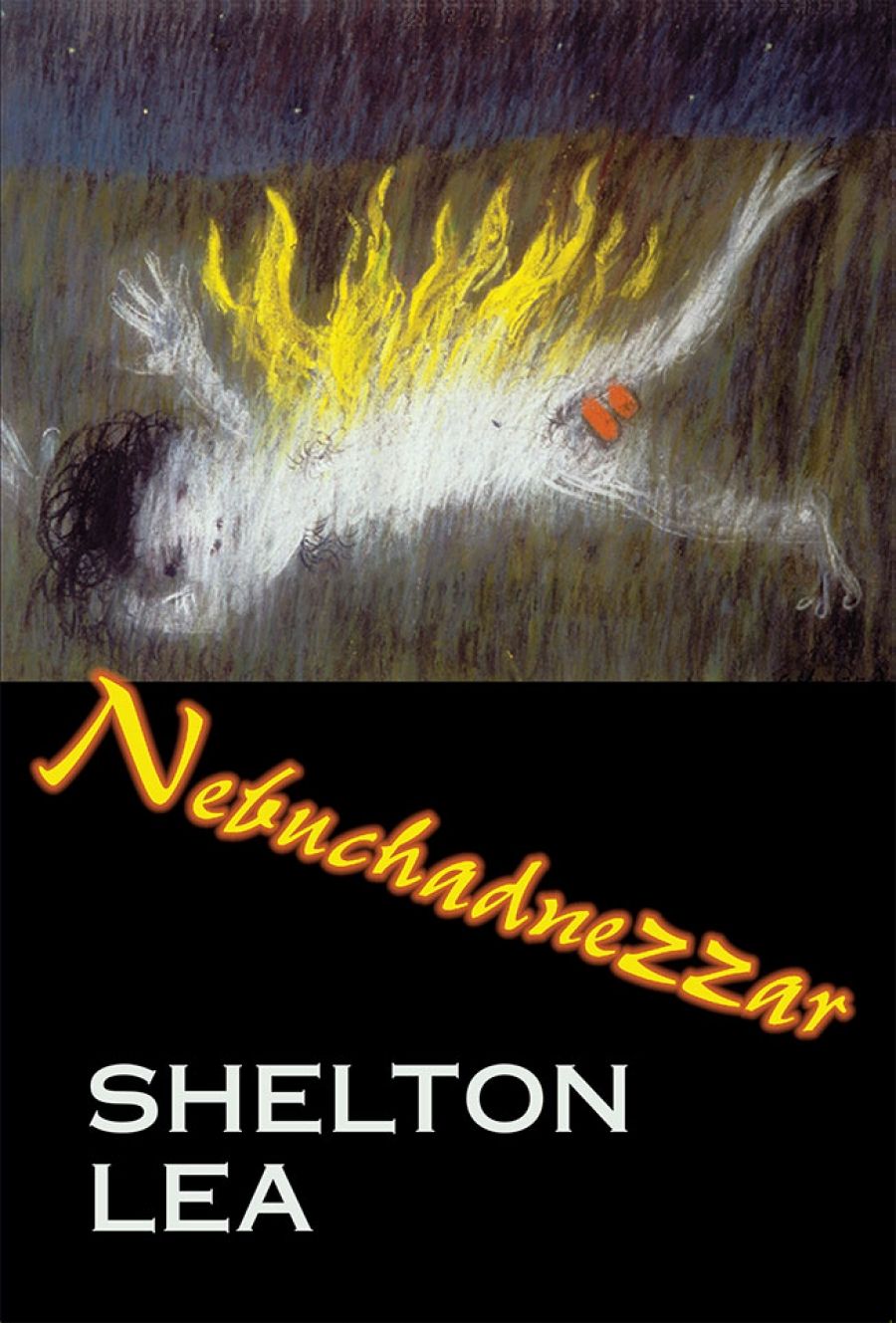

Nebuchadnezzar is Shelton Lea’s ninth and last book. Sadly, this colourful poet, a well-loved stalwart on the Melbourne reading circuit, died of cancer in May 2006, shortly after its publication.

The book begins by surveying a ‘land of fences and diatribes’ (‘1988’). It describes the inhabitants of Koori streets: ‘old men with no tomorrows / who rock on broken chairs / and stare at a bitumen sea’ (‘fitzroy’). Lea was an advocate for Aboriginal causes, and his poems often celebrate marginalised people who must summon the desire to survive. This burden of grit grounds life in harsh experience, before a remarkable lift-off.s a sort of coda, and satisfyingly resonates to the final page, in this assured début collection.

- Book 1 Title: Nebuchadnezzar

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Pepper, $23.95 pb, 123 pp, 1876044519

- Book 2 Title: Poetileptic

- Book 2 Biblio: Five Islands Press, $18.95 pb, 80 pp, 1741280923

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ezgif-3-f69088ac3e2e.jpg

Everything gains altitude (and attitude) in ‘nebuchadnezzar’, the defiant, lush and memorable title poem, in which the ancient king of Babylon, scourge of Judah, builder of the famous hanging gardens, returns to earth as a blackened but unrepentant fire-bringer: ‘i am nebuchadnezzar / … the king of fitzroy. / … trees emanate from me / for i’m the king of what’s loud … / aflame i fall through fitzroy skies.’ Lea’s beast-king declares his desires are generous, inclusive, Whitmanesque. He wants to sprout a great tree of heaven from his body, to give ‘shelter to the beasts of the field / and (let) the fowls of heaven find home along with my kin / for its leaves are as broad as the sun’.

Another standout poem is ‘at robert drummond’s, beenliegh’, about waking to an artist’s studio, where a quirky bohemian disarray reflects the poet’s own life: ‘a broken piano, / guts bare, / a pillaged muse / at the foot of my bed. / it was come dawn. / the rooster crowed as if a man / imitating a rooster, crowing.’ I like the concise self-parody here. Certainly, ‘playing the poet’ was an amusing game for Lea, his roses full and blown. But there were good biographical reasons for this. He was born in 1946 and orphaned, then ran away from his adoptive parents to live on the streets. He went to a boys’ home and did time in gaol. Although he became a successful writer, publisher and bookseller, freedom was dear to him, the mean streets never far away. Playing the footloose troubadour became a sort of dance, and a mask. With his identity as poet, Lea felt protected. He could outpace life’s ‘narks’, sidestep conventional shackles, skip mundane restraints. In poetry as in life, he liked to lead a merry dance. Lea’s flamboyance expresses a piercing joy – psychic and actual release. But don’t be fooled. It also conceals the thoughtful reserve of one who often had his heels cooled: ‘it is improper to divulge the secret of the stone, / for in the stone lies a stillness / reserved only for stones’ (‘secrets of the stone’).

Within his dance, Lea’s touchstone, his dominant tone, is always lyrical; tender and heartfelt: ‘i dream of weeds flowering’ (‘i dream of the soft slide of light’). But not every poem works, particularly where looseness invites failure. In defence, you could say Lea’s ‘artlessness’ is only superficial, tailored to appeal to the disenfranchised, who must also cobble value out of tail ends and tat. The prosecution objects, however, that this is a risky method: what is contrived to appear slipshod can quickly become so.

Finally, Lea delivers the innovative and exciting ‘autistic man’, a fractured, collage-like narrative poem about crime, a victim and how it all plays out in the mind. Here, the fine writer in Lea is fully liberated, to dazzling effect.

It is difficult to believe that Poetileptic is Mal McKimmie’s first book, for it bears the thumbprints of a seasoned poet with a fully developed sensibility, and one strongly in command of his subject matter and craft.

McKimmie suffers from epilepsy, and this is the starting point for vivid poems, often of a searing bitterness, which darkly probe various states of consciousness and being. The book has a three-part musical structure, and the first, ‘Poetileptic’, states all the main themes, in dense, image-laden, semi-narrative free verse. Just as concentrated pressure can turn decaying plants into coal, and coal into diamond, McKimmie demonstrates that art’s revenge on life is its ability to transform even pain, loss and illness into artefacts of intensity and wonder.

‘Portrait of the Poet as a Young Boy’ tells of the onset of illness in the poet’s childhood: ‘his head spun like a fly hatched in a matchbox’ when epilepsy’s ‘blue splinter’ begins its fatal journey. Other poems, some like parables or folk tales, tell of dreams, seizures, side effects, treatments, bouts in hospital and blackest rage. In ‘Practice makes Unperfect’ McKimmie describes a seizure as a ‘wild electric jitterbug of fragmentation // … the eyes upturned to watch the spirit tugging / at the cord to leave.’

In ‘Not My Heart, Not My Darkness’ the poet’s grimly comic imagination makes hospitals bearable, transforming wards into dank, ulcerated rainforests. Afloat in his bed, in a piercing and crystalline semi-delirium, he sees through a doctor’s glib mask: ‘and I watch him approach, poling up the scumming river; / an end-of-the-line colonial / bitten by the missionary bug / long ago, but jaded now, / the job a recurring fever / that he hates. / A clipboard clerk / thinned by a long tapeworm of bitterness.’

The wonderful ‘Photosensitive Rant’ repays its debt to Neruda as McKimmie praises the humble candle: ‘with a soldierly heart and a military bearing, / in its wax uniform and small cone hat of flame.’ Then he celebrates the light bulb: ‘for its fruit contours … / its brave pregnancy. / It is hot in the hands like a lover, / its light falls as soft as silk on the body.’ Savagely, he excoriates fluorescent light: ‘A cold light, and bitter’, suitable only for morgues and ‘the toe-tagged dead’, whose ‘fusion flicker’ and ‘stroboscopic snake tongue’ crazes ‘the pinhead deadspot on my brain’.

Part Two is ‘The Brokenness Sonnets’. Catching up his themes and expanding and elaborating them, McKimmie expresses a wider feeling for fellow sufferers – the deaf, wheelchair-bound, the mad and abused. The focus becomes less personal and more universal, his bitterness subsiding, the music formal and filigreed, more wrought, with an intellectual quality, a radical mindfulness. The diction softens and tone allows much-needed air to enter the lines, with poems bearing a greater delicacy and lightness.

Sonnet eighteen, ‘The Missing Link’, is a gloriously paradoxical affirmation of failure as success. Each time nature throws her genetic dice, the numbers, even the wrong numbers, become a sort of bridge into the future, as the long journey is written in our cells. It is part of the human song, to which all voices contribute: ‘you can hear me keening lonely in your past. / Search for me there. Sing your way to the speechless / centre of your wound. Then give me your song.’

The book’s third section, ‘Prelude’, is a sort of coda, and satisfyingly resonates to the final page, in this assured début collection.

Comments powered by CComment