- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Theatregoers with long memories may well hug to themselves the ‘golden years’ of the Melbourne Theatre Company’s tenancy of the Russell Street Theatre in the 1960s, a time in which plays as varied as Hochhuth’s The Representative, Peter Shaffer’s The Royal Hunt of the Sun, Feydeau’s A Flea in Her Ear, Ruth and Augustus Goetz’s infallible matinee version of Henry James’s The Heiress, and many others jostled for attention. It was the time when an actor called Clive Winmill stepped on stage in the swinging London comedy The Knack and, instead of saying his lines, treated the audience to a passionate anti-Vietnam involvement speech. It was a time when the provocative new and the venerated classic made equal claims on a theatrical ensemble which achieved real importance in Melbourne’s cultural life.

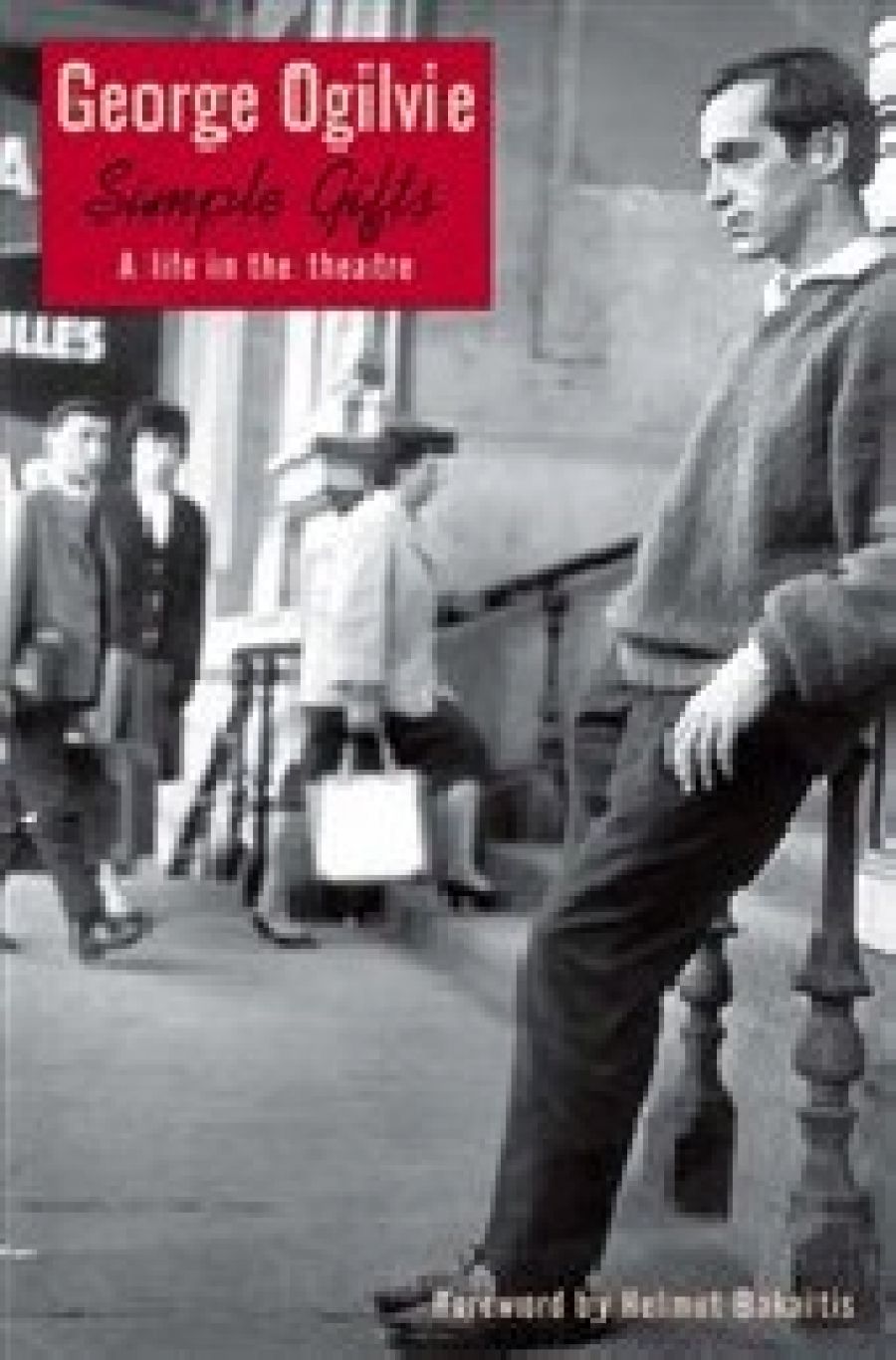

- Book 1 Title: Simple Gifts

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life in the theatre

- Book 1 Biblio: Currency House, $34.95, pb, 340 pp

If you are looking for a lot of bitchy anecdotes and well-honed one-liners, or for a trawl through the author’s sexual odyssey, characteristics so frequently found in the genre, you are out of luck. There is not even the familiar glamour-and-grind of the theatre saga as the boy from an obscure background makes his way to stellar prominence. What there is, though, is something far more valuable, and that is an extraordinarily perceptive, intensely personal, reflective account of what the book’s subtitle promises: a life in the theatre. By chance, I had just read George Baker’s The Way to Wexford (2002), a casual stroll through the ups and downs of forty years in the acting media. The contrast with Simple Gifts is acute. In Ogilvie’s book, we are in the presence of a mind equal not merely to recollecting but to assessing its past, and to offering serious insights into the profession that has nurtured and obsessed him.

Purely as a narrative, Simple Gifts has, for most of its length, an enthralling sweep, as the baker’s son from Goulburn, fired with the urge to act, makes his way first with his family to Canberra, then, accompanied by his Scots mother, returning to her home after twenty-five years’ exile, to London, the Mecca of his dreams, as it was for so many young Australians in the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, one of the best things about this book is its sense of history of the recent past: the Depression and the mindsets of those who survived it; the idea of Australia as still being a sort of colonial out-post in the wake of World War II; the meagre place allotted to the arts in this country at that time; the inevitable pull of Europe; and, later, a feeling that we had grown to a point of recognising – and no longer accepting – the patronage of the ‘mother country’. All this and more is made palpable, along with Ogilvie’s own personal history.

He not only wants to be an actor, he needs to be one. Ogilvie evokes the youthful aspirant ready to do anything to learn his craft in a way that I have rarely read elsewhere. As an account of life in a ‘fit-up’ repertory troupe (The Family, as he will come to describe the Midland Touring Company, his first employers in the United Kingdom), Simple Life recalls Michael Blakemore’s unsentimentally endearing novel, Next Season (1969). The threat of National Service in Britain sends him back to Australia, to work with the Canberra Rep; to the start of a National Theatre here, tied as it initially was to British apron strings; to the Melbourne Union Theatre Repertory Company (later the MTC at Russell Street); to the culmination of every sort of dream with an opera, a ballet and a play simultaneously occupying the Sydney Opera House.

Not that this happens in an unbroken line. There are returns to London, to Paris to study mime with Jacques Lecoq, and, increasingly important, the spiritual questing that takes him to ashrams at home and in India, to find peace among the Franciscans in Assisi, to camp beside the Sea of Galilee. The two aspects of his life are not seen in mutual exclusivity. The dedicated man of the theatre – the man who moulded the ensemble that produced a cherishable Three Sisters – is seen finally to be a changing and growing entity that finds the sacred in the profane, tranquillity in turmoils. The book has a wonderful cast of characters for whom there is not space here to do justice. It offers real insights into the dedicated life, in particular to how absorption in the theatrical world both narrows and enlarges life.

Frequently touching about other people (his mother’s return to her Scottish roots, for instance), Ogilvie’s book finally moves one by the dual suggestion it offers of a life rich in achievement and of a curious sense of distance from the closest kinds of relationship. Perhaps this is just the author’s single-mindedness and reticence at work in a book that really knows what it is about.

Comments powered by CComment