- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Some years ago, Robert Hughes bemoaned the capitulation of art museums and galleries to ‘the whole masterpiece-and-treasure syndrome’. Although made in the 1980s, Hughes’s point may still be valid, especially if the number of recent exhibitions with the word ‘master’ in their titles is anything to go by. A quick check reveals that, in Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria is particularly fond of the word. In Melbourne last year, we had ‘Dutch Masters from the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam’ and ‘Albrecht Dürer: Master of the Renaissance’. In 2004 the NGV put on ‘The Impressionists: Masterpieces from the Musée d’Orsay’.

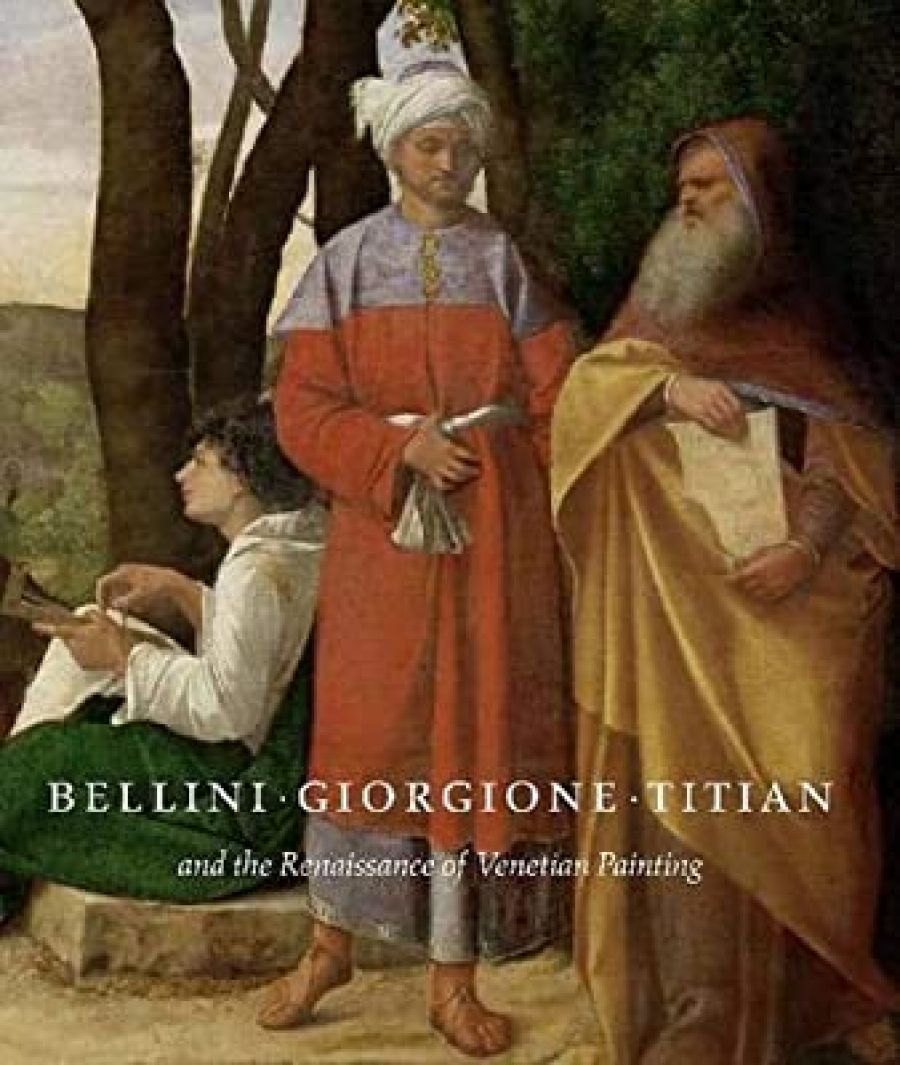

- Book 1 Title: Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press, $130 hb, 336 pp

Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting takes a different approach to its recent predecessors. As the catalogue indicates, the curators David Alan Brown and Sylvia Ferino-Pagden have eschewed the biographical for the thematic. The exhibition and catalogue are divided into sections, each of which has a guest curator or compiler. Peter Humfrey has contributed a section on ‘Sacred Images’, Mauro Lucco on ‘Sacred Stories’, Jaynie Anderson on ‘Allegories and Mythologies’, Sylvia Ferino-Pagden on ‘Pictures of Women – Pictures of Love’, and David Alan Brown on ‘Portraits of Men’. The result is a compelling new narrative of the development of Venetian art in the first three decades of the sixteenth century. Major works of the importance of Titian’s Concert Champêtre (exhibited in this exhibition for the first time in the United States), Giorgione’s Three Philosophers and Bellini and Titian’s Feast of the Gods have been included alongside paintings by slightly lesser known, though by no means obscure, artists of the Venetian school, such as Lorenzo Lotto, Sebastiano del Piombo, Cima da Conegliano and Palma Vecchio, among others.

The format allows each of the contributors, all of whom are leading experts on Venetian art, to make broader than usual comments and observations. Lucco’s essay provides a particularly good example. After a general discussion of the ways in which Venetian artists treated religious narrative subjects, he moves on to give a valuable new account of the rise of landscape in paintings of the period. It is an intriguing fact that landscape painting was pioneered in Venice, which was and is an almost entirely urban environment. Lucco rightly notes that in the work of Giovanni Bellini the landscape background is nearly always conceived of as a landscape of use rather than one of natural beauty. In Giorgione, however, the landscape becomes a bucolic place of escape, a locus amoenus.

The Allendale Nativity is a key work in this development, which reaches its apogee in the Concert Champêtre. In the former painting, Giorgione took the radical step of placing Christ off centre to the right. As Lucco suggests in his excellent catalogue entry, this allows nature itself to take centre stage as a ‘protagonist’ of the painting. Even so, however, ‘the rusticity of this pastoral life is completely fictional and is, in fact, its opposite, the product of cultural sophistication’. No doubt that has always been the case. We are probably incapable of approaching nature in an unmediated way (though perhaps not quite as mediated as the aptly named Sir George Beaumont, who travelled around eighteenth-century Britain with a landscape painting by Claude Lorraine, pausing at well known beauty spots to compare the view with the painting).

At the end of the catalogue, there are two valuable technical studies, an almost obligatory appendage these days in publications on Venetian painting. In the first, Elke Oberthaler and Elizabeth Walmsley note that our knowledge of the working methods of the Venetian painters has been greatly enlarged through X-radiographic and infrared reflectogram analyses of their works. Infrared photography and infrared reflectography have revealed that, contrary to received opinion (beginning with Giorgio Vasari in the sixteenth century), Venetian artists did indeed make drawings, if not the elaborate preparatory drawings on separate sheets of paper of the Florentine school. Instead, the Venetians drew their compositions directly on the support before painting over them. These under-drawings form a significant, if concealed, corpus of drawings. The second technical study, by Barbara H. Berrie and Louisa C. Matthew, is a fascinating essay on what they call the ‘industry of colour’ in Renaissance Venice. The emphasis on colore in Venetian painting has always been remarked, but painters were not the only participants in this industry. In fact, the profession of vendecolori (colour sellers) was unique to Venice until the second half of the sixteenth century. As Berrie and Matthew make clear, elsewhere in Europe, painters bought their pigments from apothecaries.

In one of three informative essays that precede the thematic sections (on the society and culture of Venice, problems and issues in the history of Venetian painting, and relationships between artists during the period), Deborah Howard points out that the first decades of the sixteenth century were troubled and difficult ones for Venice. In 1509 the League of Cambrai invaded the Veneto, stripping Venice of virtually all her possessions on the terra firma. During the same years, the city also experienced recurring epidemics of plague and a number of economic crises. This is the unpromising context in which Bellini, Giorgione, and Titian produced some of the greatest paintings of the European tradition.

Yet perhaps it is precisely for this reason that Venetian art of this period accomplished so much. It does not seem coincidental, for example, that, at the very moment when Venice’s dominions on the mainland were being taken from her, Venetian artists were painting evocative landscape idylls and pastoral paradises. It would have been difficult to imagine a more dystopian present. In this, the artistic achievements of early sixteenth-century Venice look forward to those of the twentieth-century avant-gardes. Piet Mondrian’s abstract paintings, for instance, were made against the backdrop of two world wars and were intended as harbingers of a future, utopian society; a modernist equivalent perhaps of the Venetian locus amoenus.

Comments powered by CComment