- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As a middling country far from the centre of major world events, Australia has usually bobbed about in the wake of greater Pacific powers. After being a dependency of Britain for nearly two centuries, the country was accustomed to having its fate decided by distant power brokers. Yet Australian leaders occasionally attempted to strike out on their own in pursuit of what they saw as distinctively Australian interests. Alfred Deakin did it in 1908 when he ignored the usual diplomatic niceties of consulting the British Foreign Office before inviting the American fleet to visit Australia; Billy Hughes did it with his grandstanding at the Versailles peace conference of 1919; and Robert Menzies and John Curtin did it during the desperate days of mid-1941, when they tried to keep Japan out of the war, as British Empire forces struggled to maintain their tenuous hold on the Mediterranean.

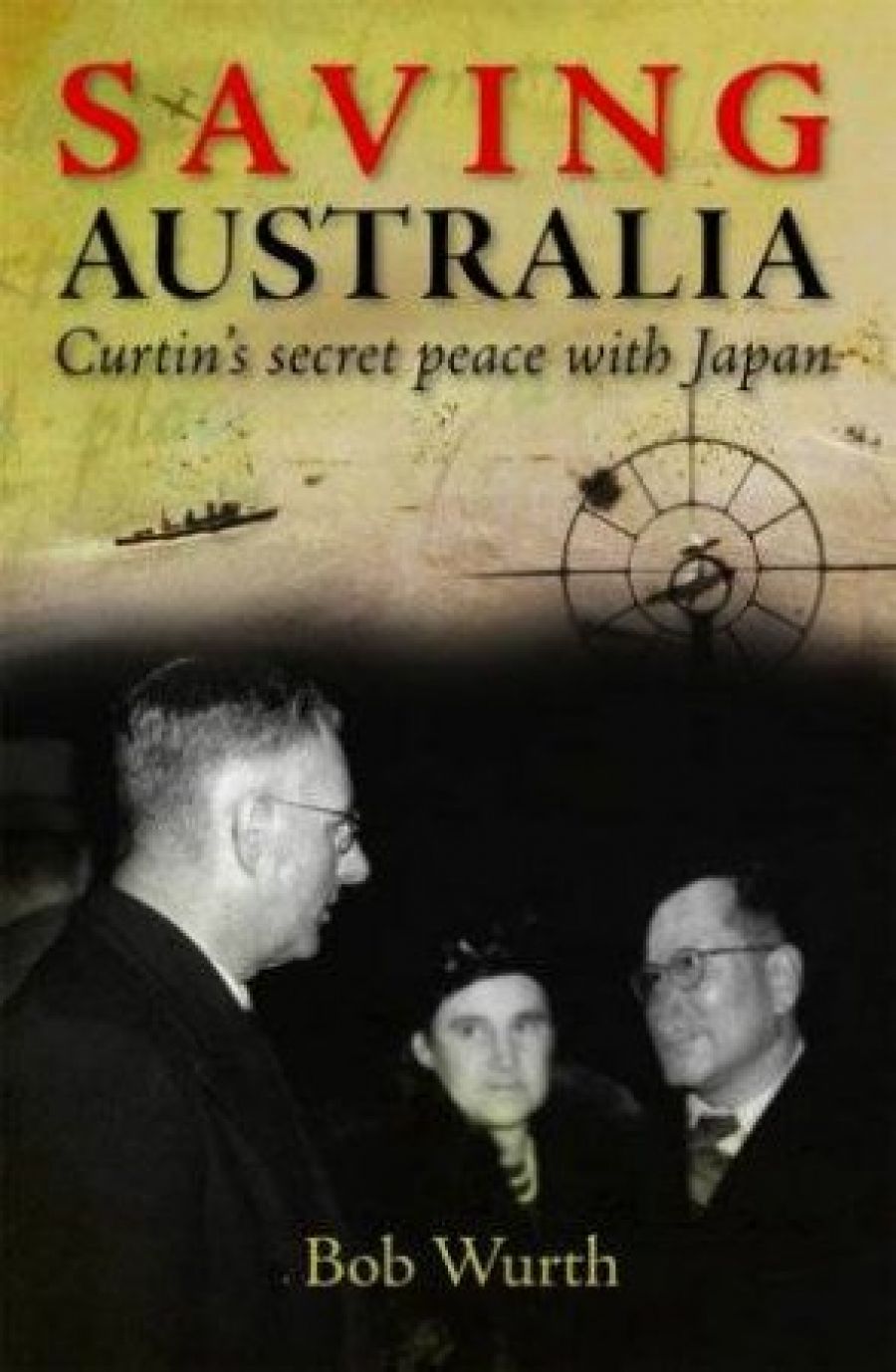

- Book 1 Title: Saving Australia

- Book 1 Subtitle: Curtin’s secret peace with Japan

- Book 1 Biblio: Lothian, $34.95 pb, 351 pp

Both Menzies and Curtin were trying in their different ways to dissuade the Japanese from attacking the resource-rich European and American colonies in South-East Asia. As prime minister, Menzies was in London pressing the British government to strike a deal with Japan that would allow for limited Japanese expansion in the Pacific. As Opposition leader, Curtin was pursuing the same ultimate aim in Australia of averting a Pacific war. With the concurrence of the government, he had repeated talks with the newly arrived Japanese representative, the propagandist and sometime poet, Tatsuo Kawai. It is the relationship between Kawai and Curtin that Bob Wurth examines in his richly textured book Saving Australia: Curtin’s secret peace with Japan. Despite Wurth’s subtitle, there was no ‘secret peace’, but there were talks about how such a peace might be achieved, with Australia offering the Japanese access to iron ore deposits in Western Australia in return for Japan not entering the war.

With most of Australia’s troops, naval ships, and air force serving on the other side of the world, and with no prospect of Britain fulfilling its historic guarantee to send a fleet to Singapore, it was not surprising that Australian leaders were anxious to discourage Japan from pursuing its wider imperial ambitions. How far the talks between Kawai and Curtin went remains a matter of contention, since much of the documentation did not survive the war; but it seems that they petered out well before Curtin became prime minister in October 1941, although Labor’s External Affairs Minister, Dr H.V. Evatt, went on seeking peace right up until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

In the event, all the talking was in vain. Neither Curtin nor Kawai was in a position to change the course of events in which they played but minor parts. For their different reasons, both Britain and the United States were determined to constrain Japan and were resigned to the early forfeits that war with Japan would bring, confident that eventual victory would be theirs. Moreover, the offer of Australian iron ore would never have been sufficient to keep Japan out of the war, since it was access to oil supplies that Japan most needed to ensure the successful prosecution of its war in China. For that, it would have to strike out for the Netherlands East Indies.

Wurth’s book would have been much slimmer had he restricted its focus to the talks between Curtin and Kawai. However, he has ranged much wider to paint an absorbing picture of Japanese activities in Australia during the early years of the war, as their diplomatic and commercial representatives attempted to court the favour of Australian business and political leaders. Wurth regales his readers with tales of diplomats plying garrulous Australian politicians with alcohol and having their Australian chauffeur take them on a tour to inspect the vital BHP steelworks and its defences at Newcastle.

Apart from the espionage and the socialising, Wurth also explores the emotional life of Kawai, who had become besotted with a young Japanese-American woman whom he had met in Tokyo. She had joined the Japanese diplomatic service and been trained in flower arranging and the art of the tea ceremony before Kawai had her sent to Melbourne, where she acted as his secretary and the hostess of his social gatherings.

In the end, all the socialising and the spying was for nought. War could not be averted, and Japan would discover that its imperial ambitions were greater than its capacity to achieve them. While the fighting still raged, a saddened Kawai was repatriated home to an uncertain Japan, taking with him the ashes of four sailors killed in the unsuccessful submarine attack in Sydney Harbour. Yet the friendship between Kawai and Curtin remained alive, and was sustained after the war by their respective families.

Comments powered by CComment