- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: International Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When I started reading My Israel Question, the Israel Defence Force Chief of Staff had just vowed to ‘turn back the clock in Lebanon by twenty years’; and the demolition was underway. Beirut’s airport, major roads, bridges, power generation facilities and other civilian infrastructure had been bombed, and villages and densely populated suburbs were being reduced to rubble. In a report some weeks later (August 23), Amnesty estimated that 1183 Lebanese had been killed, mostly civilian, about one-third of them children. The injured numbered 4054, and 970,000 people were displaced; 30,000 houses, 120 bridges, 94 roads, 25 fuel stations and 900 businesses were destroyed. Israel lost 118 soldiers and 41 civilians, and up to 300,000 people in northern Israel were driven into bomb shelters. Israel estimates that Hezbollah, the putative object of its wrath, lost about 500 fighters.

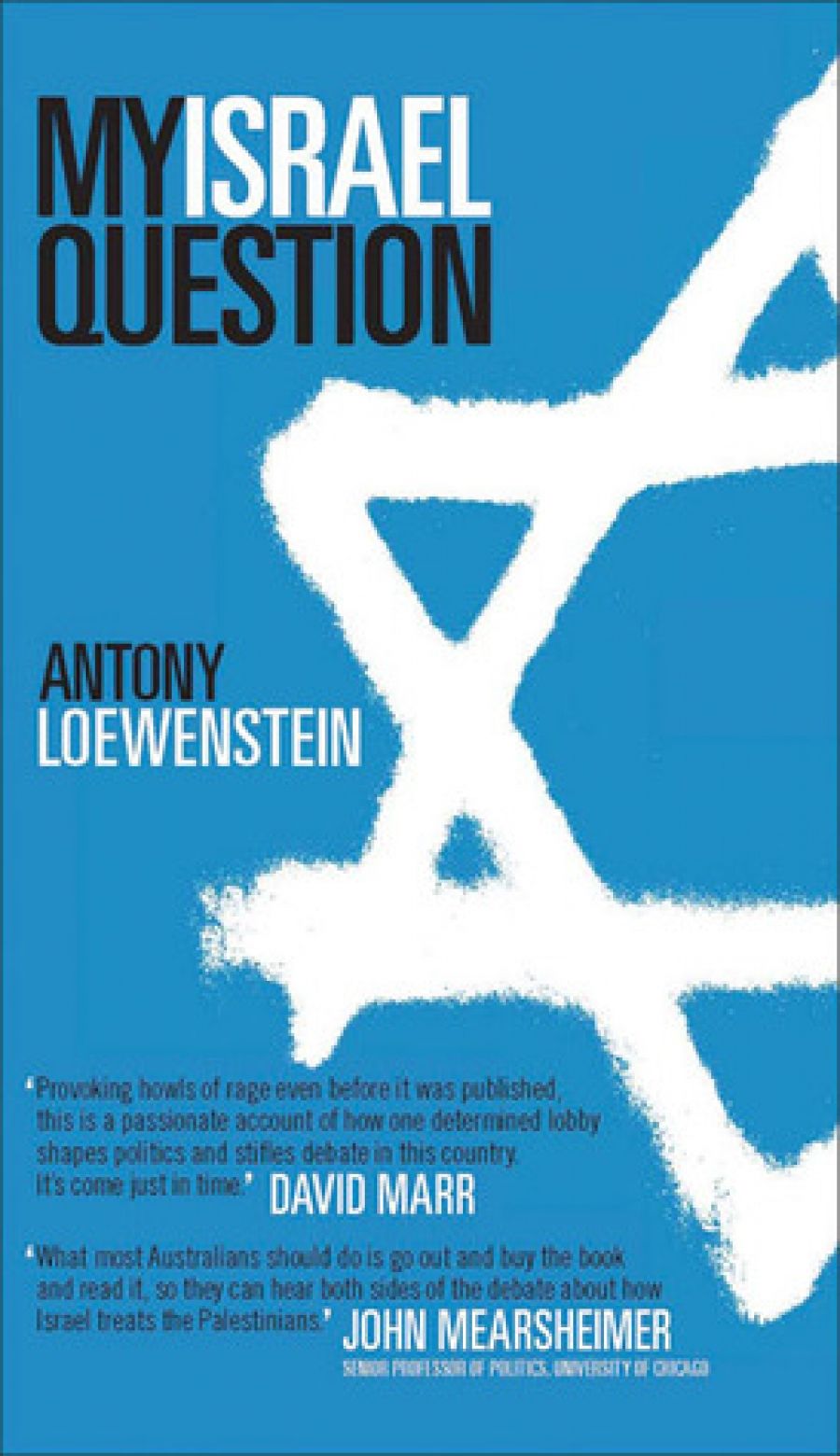

- Book 1 Title: My Israel Question

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $32.95 pb, 340 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/PX26Q

The offensive was an atrocity. Within a fortnight of its commencement, the United Nations’ Secretary General and its Human Rights Commission, Amnesty and Human Rights Watch (HRW) accused Israel of committing numerous war crimes. Hezbollah was also accused, but more sparingly. Given its restricted military capacity, Hezbollah patently lacked the same opportunities for criminal destruction. Kenneth Roth, director of HRW, accused the Israeli military of having a ‘disturbing disregard for the lives of Lebanese civilians’ and of deliberately targeting them. Amnesty concluded that ‘many of the violations ... are war crimes. The pattern, scope and scale of the attacks makes Israel’s claim that this was collateral damage simply not credible.’ Most nations with an interest in the war condemned Israel for the use of disproportionate and indiscriminate force. The United States and Britain, however, did not; they temporised in the United Nations and facilitated the carnage. As usual, Canberra parroted the American line: Israel had the right to defend itself. This expedient refrain averted questions about the proportionality and justice of Israel’s offensive.

Initially, statements by Israeli officials suggested that the aim of the offensive was to undermine Hezbollah by punishing and turning the Lebanese population against it. This rhetoric, if not the intention, was soon abandoned, presumably because it was so transparently criminal, not to mention unintelligent. It was replaced by language more focused on the return of the soldiers – whose abduction triggered the war – and the extirpation of Hezbollah. This was no doubt considered more palatable, especially in the light of the view expressed by Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations that Hezbollah were ‘ruthless, indiscriminate animals’. Among the awful statistics were the polls indicating (initially) that more than ninety per cent of Israelis approved of the war and that almost as many approved of attacking civilian targets.

Meanwhile in Gaza, the efforts of the IDF to retrieve an abducted soldier, which had been almost completely obscured by the mayhem in Lebanon, continued. Between June 27 and August 8 the IDF killed 170 Palestinians, of whom 138 were civilians, about a quarter children; 506 were injured.

Antony Loewenstein’s ambitious and combative book is not directly about Israel’s recent adventure in Lebanon or the ‘rescue operation’ in Gaza, but its chief contentions could scarcely have been more vividly illustrated than by these murderous exercises. In part, it relates a story of self-discovery: a Jewish Australian boy discovers that he is born into the wrong side of a horrible conflict, recognises the injustice that many of his people are wreaking on another, and decides to do what he can to rectify it. Because he is a journalist and not a freedom fighter, that decision meant, of course, entering the arena of public debate. The bulk of the narrative, however, is a vigorous assault on Israel’s occupation of Palestine and on the people who support it, conducted in the manner of contemporary ‘current affairs’ writing: that is to say, a mixture of history, second- and third-hand sources (newspaper reports of reports), impressionistic sociology, and excerpts from interviews with pundits and other journalists. There is much to be said against Loewenstein’s book – and if he is right about the ‘Zionist lobby’, then that, and more, will be said – but the flaws are redeemed by the great merit of the book being, in my judgment, largely true.

Loewenstein lays the blame for the troubles in Palestine squarely at the feet of Zionism. He is not deeply interested in Zionism as a religio-nationalist ideology, as was Jacqueline Rose, for example, in her recent, equally severe The Question of Zion (2005), though the book does contain some perfunctory discussion of it. He is primarily interested in Zionism as a geopolitical phenomenon expressing itself in the ruthless appropriation of land in Palestine, the oppression of some of its indigenous people, and the baleful influence of Zionist lobbies on governments and the media.

Broadly, Loewenstein sees things this way: the 1947 UN Resolution partitioning Palestine and creating a Jewish state was an historic injustice to the Palestinians. Ethnic cleansing of Palestinians began almost immediately and was sanctioned by the Zionist leadership. Loewenstein cites Benny Morris, one of the Israeli ‘New Historians’, who uncovered the early history of ‘transfer’ (and later sought to palliate it): ‘There are circumstances in history that justify ethnic cleansing ... A Jewish state would not have come into being without the uprooting of 700,000 Palestinians ... The need to establish a state in this place overcame the injustice that was done to the Palestinians by uprooting them.’ Since then, and especially since the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967, there has been a more or less continuous policy of expulsion and expropriation. ‘Mass confiscation of land, acts of collective punishment, arrest without trial and house demolitions became the norm. Virtually every Geneva convention related to areas under occupation was abused.’

The illegal occupation of Palestinian land and the continuing construction of Jewish settlements is the central, unavoidable fact in the current conflict. It is the cause of legitimate Palestinian resistance. The resistance in turn has generated still more brutal, oppressive and illegal measures. Every assault on its people is perceived by Israel and much of the Jewish Diaspora as representing an existential threat that justifies extreme responses: the assassination of resistance leaders, notwithstanding the collateral killing of many innocents; the demolition of dwellings belonging to the kin of suicide bombers and fighters; economic strangulation; the construction of illegal barriers, and restricted roads and neighbourhoods; and restrictive citizenship laws for Palestinians. Israel has transformed itself into a violent apartheid state, unconscious of its brutality and lawlessness. Beneath the unilateralism and hauteur – the delusion that it can do anything to defend its interests – Loewenstein detects the animus of ‘a long history of racist superiority’. The fact that successive elected governments have continued to act so obdurately suggests that the Israeli polity is saturated by dehumanising racist contempt or indifference. The Palestinians have concluded that, despite the rhetoric, Israel doesn’t want peace; or, rather, that it does, but uncompromisingly on its terms: currently, that seems to involve an Israel expanded well beyond the internationally recognised 1967 borders and a weak, scattered Palestinian state in ‘permanent neo-colonial dependency’.

The influence of a pro-Israel lobby on American Middle-East policy, the questionable roles of some senior Jewish officials in the Bush administration, and the worrisome relations between the administration and Christian Zionist groups, have been the subjects of serious scrutiny lately. Loewenstein also goes over this turf, though comparatively lightly, and he is more interesting and scrupulous on the Australian scene. He says that in Australia the Zionist lobby – a heterogeneous group of organisations and élite individuals with access to the corridors of power – ‘exercises demonstrable influence over Australia’s political élite’. The evidence presented for such influence – at least on the governing parties – is pretty slim and, in any case, influence per se is not an offence. It is not news that representatives of influential constituencies gain politicians’ ears or that rich men have access to prime ministers. In the United States, there are currently acute questions about whether some pro-Israeli elements have operated illegally and whether pro-Israeli influence has operated to the detriment of American interests. There are no such corresponding issues here. Although the Howard government is evidently close to some Jewish groups and Howard is personally close to some of their leaders, the congruence between their perspectives on the Middle East seems so complete as to suggest that the exercise of influence would be quite superfluous.

Loewenstein is on more fertile ground in discussing the efforts of some Zionist lobby groups to influence media programming and content, especially in the ABC and SBS. The chief villain here is the Australia/Israel and Jewish Affairs Council: ‘In AIJAC’s opinion, any news story that portrays Israel in a critical light is biased, irresponsible and a sign of anti-semitism.’ Reporters and media senior manage-ment are said to be subjected to ‘intense pressure’, ‘harrassed’ and ‘intimidated’: ‘there is no doubt that concerted campaigns by AIJAC and other lobbyists are wearing down journalists and other media professionals ... the fear of being attacked by lobbyists is directly leading to certain subjects or perspectives being ignored or side-lined.’ Loewenstein reports himself as having come under heavy fire, although the appearance of his book shows that the lobbyists’ success rate is less than perfect.

Lobbying in itself, of course, is not problematic where there are sufficient counterweights, journalists are not shrinking violets, and the instruments of influence are legal and decent. The reckless aspersion of anti-Semitism (or of being a self-hating Jew) used to try to silence Israel’s critics is indecent. Loewenstein is understandably concerned with this device, and expatiates on the obvious requirement in argument to distinguish between the content of critique and its motivation. Even mild criticism of Israel often provokes furious (and irrational or silly) responses in the opinion pages and letter columns, charges of anti-Semitism, and slander on the internet. Loewenstein seems to think that these reactions are mostly part of an organised political strategy of intimidating critics: ‘The only way to defend an illegal and brutal occupation is to be constantly on the offensive.’ I am inclined to think that much of the (over)reaction, including from the apparatchiks and lobbys, is frequently projection and stems from guilt and shame. If that is right, then the picture is sadder still than Loewenstein understands.

I hope it will not appear contrary to end by affirming that My Israel Question is a flawed and one-sided book. The writing is often slack and hasty, and wobbles under the effort of holding its citations together; there are sixty dense pages of footnotes. It wants careful editing: whole pages are chaotic mysteries. More seriously, the sympathy so evident for the Palestinians and their Arab neighbours is entirely withheld from the Israelis, who are (still) also victims: of history, of their own blind actions, of Palestinian hatred. Loewenstein barely mentions Palestinian atrocities, the suicide bombings targeting children, the mass murders and so on. He seems oblivious of the dynamics of fear and of the exigent obligations of a state to defend its citizens. He does not distinguish between those state measures that are intentionally oppressive of Palestinians and those that defend against terrorism. He swiftly passes over the vengeful Jew-hatred that has taken on a destructive and obstructive life of its own. There is no serious consideration of what a just, feasible solution to the wretched state of affairs in Israel and Palestine could look like: it may be too late for there to be one. Loewenstein has cast his story as the first act of a simple David (Palestine) and Goliath (Israel) morality tale, when really what it tells of is an unrelieved tragedy.

Comments powered by CComment