- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Louder thunder

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The accounts of childhood in this anthology date from the 1920s to the 1960s. Most deal with experiences in Western Australia, although three are written by migrant women and are partly anchored in Europe. Two are extracted from the autobiographies of well-known writers, Dorothy Hewett and Victor Serventy, two are taken from self-published memoirs, and one, by Alice Bilari Smith is taken from her book Under a Bilari Tree I Born. This last is based on tapes of oral history collected by the West Pilbara Oral History Group and published in 2002.

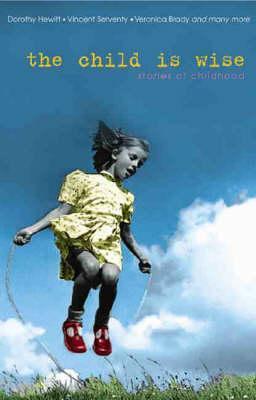

- Book 1 Title: The Child Is Wise

- Book 1 Subtitle: Stories of childhood

- Book 1 Biblio: FACP, $24.95 pb, 351 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The Child Is Wise is a fascinating collection, not so much on literary as on cultural, historical and psychological grounds. There are, of course, multiple reasons for readers’ perennial interest in memoirs of childhood. One of the more obvious is the fact that early memories are usually the most vivid and acute. ‘In childhood everything was different,’ according to the Russian writer Konstantin Paustovsky. ‘Everything was more vivid – the sun brighter, the smell of the fields sharper, the thunder was louder, the rain more abundant and the grass taller.’ This diverse collection, which mostly does not disappoint in reproducing the hyper-experiences of childhood, suggests other reasons as well. Many probe the extreme vulnerability of the child: physically and emotionally subject to the powerful personalities of authority figures, to the taboos of culture and to the impact of mysterious but catastrophic world events.

To my mind, the most remarkable narrative in this con- text is Josephine Cabassi’s ‘From My Beloved Mountain to the Garden of Eden’. Born into a poor mountainous area of Italy, Cabassi eloquently describes the daily life of her small childhood community and the rigours of poverty, especially after her father and then her brother left for Australia and the family had to survive with only one parent for several years. Then, in 1937, came the extraordinary migration to her father’s farm in Western Australia and her adjustment to its stark difference from her imaginings. Cabassi’s narrative ends with her transgression of one of her culture’s most powerful taboos, when she became pregnant out of wedlock. Her father’s inability to come to terms with this situation, even though her lover had earlier proposed marriage, caused Cabassi much sadness. Absent from her first Holy Communion and from her confirmation, her father did not even attend her wedding. ‘If only he had sent his blessings, it would have made such a difference, but there was no word from him whatsoever. No wishes, no blessings, nothing. Even now, weddings bring a sadness to my heart.’

This narrative shares some features with others in the collection, besides an orthodox or rigid father. Cabassi’s emotional attachment to place, especially to her Italian home, is similar to Hewett’s eloquent if more ‘writerly’ descriptions of her wheat and sheep farm in Western Australia, and to Essi Rossi’s memories, in ‘A Letter to My Grandchildren’, of the Jewish ghetto in East End London where she lived in the 1920s and 1930s. Acute insecurity sharpens some episodes in Cabassi’s narrative, especially when her mother is reduced to smuggling and is eventually arrested and jailed. Rossi suffers similarly when her family, apparently unable to make a secure living, moves from one rented home to another as a means of evading payment. The bullying and physical punishments of his boarding school tarnish Tally Hobbs’s otherwise mellow memories in ‘The Bungalow’; Natalie Andrews recalls the unpredictable and terrifying violence of her father in ‘Clara’; and Alice Bilari Smith revisits the frightening impact of her stepfather’s murder when she was ten. Invariably, these experiences are recalled with immediacy, from the child’s powerless but fatalistic point of view, as inexplicable and unpredictable.

Fathers are often uncontrollable or awe-producing figures, but not invariably so. Alice Bilari Smith recalls both her white father and her Aboriginal stepfather with affection, clearly regarding herself as fortunate in having two, while Meg Aldridge’s father in ‘Go Steady on the Sugar’ is a warm counterbalance to a repressive mother. If fathers can be physically abusive, mothers may be prone to psychological abuse, as in two of the stories here. In other accounts, the vulnerable situation of the mother increases the insecurity of her child, as in the narratives by Rossi, Smith and Cabassi. Tally Hobbs’s mother committed suicide shortly after his birth, but his grandmother is a loving replacement, while his grandfather takes over the paternal role largely abandoned by his father. If parents are powerful authority figures, several of the particular cultures explored here provide them with their authority, even as they limit adult sensitivity and empathy. Bilari Smith’s life is bounded by the absolute authority of ‘the Law’; neither Hobbs nor his grandparents question the requirement that he attend a prestigious but brutal boarding school; Cabassi follows her mother’s example in stoical acceptance of inequity.

Harrowing as some of these accounts are, they are generally balanced by a mature, forgiving perspective on the exigencies of the past, so that the reading experience is a far from demoralising one.

Comments powered by CComment