- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Legal magic

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Peter Russell, a distinguished Canadian student of the politics of the judiciary, asks if ‘my people’ – the English settlers of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the US – can live honourably. Is their authority defensible against indigenous people’s charge that ‘my people’ bullied them out of their sovereignty? Because European colonial power has been shadowed by a sense of moral unease, interpreting the colonists’ laws matters. ‘There is a lot of leeway in the law,’ Russell observes, ‘and no more so than in legal cultures based on the common law.’ The High Court of Australia’s decisions in Mabo (1992) and Wik (1996) – making native title recognisable to the common law – seemed to Russell to confirm judges’ potential to be the conscience of liberal constitutionalism.

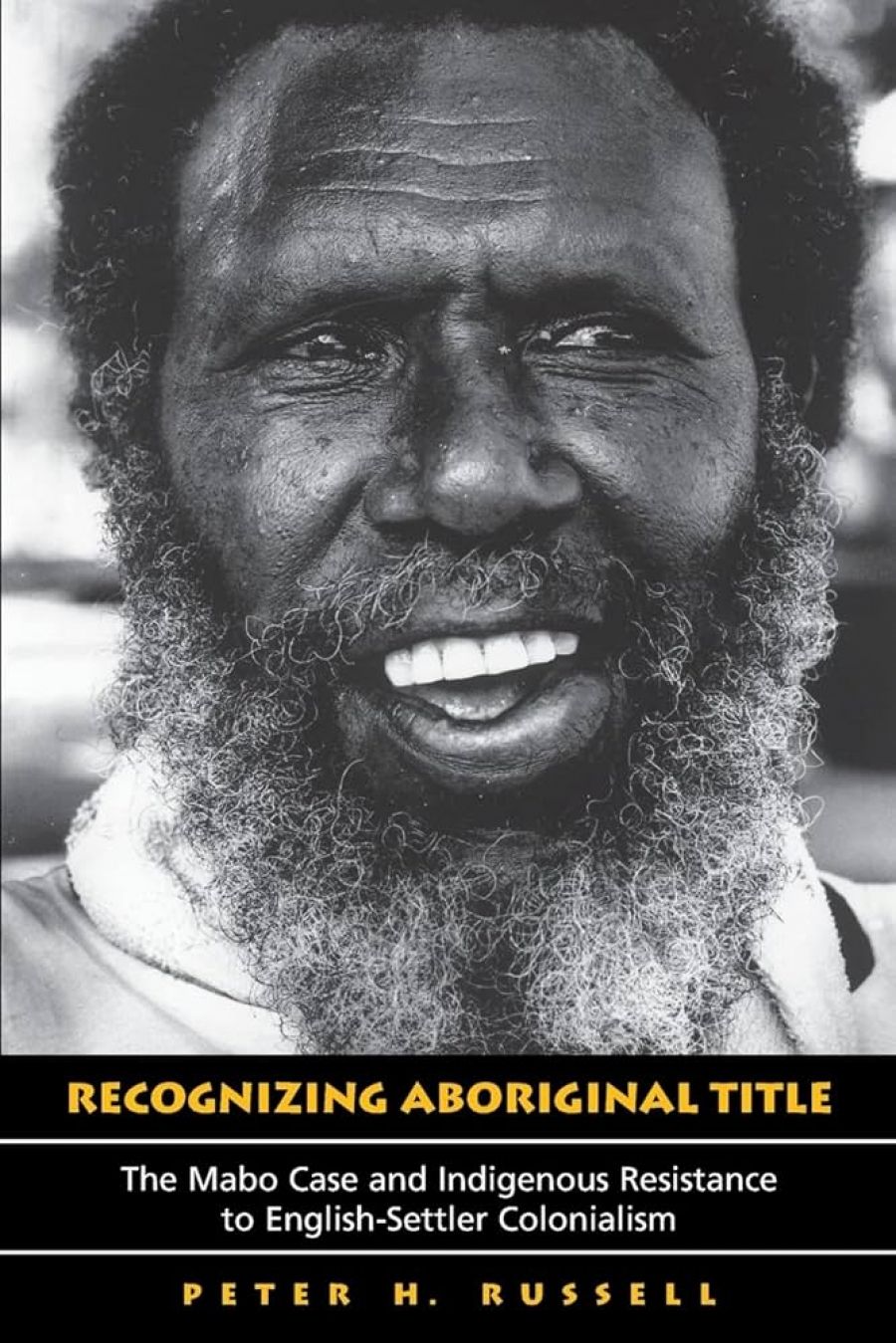

- Book 1 Title: Recognizing Aboriginal Title

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Mabo case and Indigenous resistance to English settler colonialism

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Toronto Press, $130 hb, 470 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

But do indigenous people think that the colonists’ law is available to them? Judges without plaintiffs cannot be channels of moral unease. Eddie Mabo shines for Russell because he did not give up believing that in the law of the land imposed by Russell’s people he would find remedy for the Crown’s unjust assumption that Torres Strait Islanders did not own their ancestral country. His faith was tested in 1990 when Judge Moynihan (in Mabo and others vs the State of Queensland and Another) did not believe his claim to be an owner of certain plots of land on the island of Mer. Mabo’s anguish did not stop him and other Islanders from going to the High Court, because Moynihan (determining certain matters of fact for the High Court) did believe that David Passi was a landowner, and possibly James Rice as well. If landowning was subject to customary law ‘probably antedating European contact’, then the High Court had a case to hear. Prompted by a question (a judicial hint?) from Judge Deane, the plaintiffs amended their claim, at the end of their presentation, from assertions of individual title to a declaration of the Islanders’ collective title.

In Russell’s view, the High Court’s recognition of native title created a threshold for Australia’s constitutional reform. ‘Constitutionalism is about the nature of the body politic – the political community and the people or peoples who constitute it.’ The most important feature of the Australian Constitution is thus its silence on the relationships among Australian peoples. Mabo did us the courtesy of pointing out this elephant in the room.

Compared with the other nations made by Russell’s people, is Australia legally, politically and morally retarded? Russell says that Australia is more like than unlike Canada, New Zealand and the US. All four countries find it easier to contrive ‘top-down legislated solutions’ than to negotiate agreements.

However, Russell has much to say about Australia’s difference. Australian federalism has always afforded the states a greater say over indigenous affairs than in Canada and the US, and ‘states’ rights’ have tended to trump indigenous rights. Australia is also ‘one of the last outposts of legal positivism’. In professional culture and in popular opinion, Australians are recent and reluctant ‘legal realists’. Suspicious of judges’ discretion, Australians ascribe integrity to judgments, such as Blackburn’s 1971 ruling against the Yirrkala plaintiffs, that bind the nation to legal precedent and disregard moral intuition about the facts of history and ethnology.

The four settler colonies have tried not only to assimilate but also to segregate. However, in Australia, segregation was the stronger tendency until 1939, writes Russell, because the racial pessimism of ‘my people’ was deeper about Aborigines than about Maori or Indians. Habits of racial thinking persisted in Australia after 1939, to the extent that ‘assimilation’ was widely understood to include ‘breeding out the colour’. Many Australians are now sceptical of a person who asserts Aboriginal identity even though he or she is physically ‘white’. For Australians to understand the settler–indigenous relationship as a relationship between ‘races’ is a barrier to ‘true reconciliation’, he writes.

Perhaps Russell pays too little attention to the ways that Australian geography has nourished this racial idiom. Pessimism about land has been as important as pessimism about its indigenous inhabitants; the unpromising lands of the north and centre left these regions and their peoples ‘remote’ from colonising effects and ripe for ‘decolonisation’ when the ‘winds of change’ began to blow in the 1950s. (In its provision of reserve lands, Russell remarks, ‘Australia compared rather well with other English-settler countries’.) As he points out, it was to the Murray Islanders’ advantage that European agriculture had not overrun their land. In contrast, the arability of the Yorta Yorta people’s land summoned the ‘tide of history’ (in Judge Olney’s phrase) that washed away the evidence that the law required for their late twentieth-century native title claim. Reformed land laws in Australia set cultural tests for indigenous claimants; when the exam is passed by ‘remote’ Aborigines or Islanders, it acquires the appearance of fairness. In the distinction, dear to Australian opinion, between ‘real’ and spurious Aborigines, racial, cultural and geographical thinking have long reinforced each other.

Australia has no tradition of making treaties with indigenous peoples. Does this matter? Treaties did not relieve Māoris and Indians of being ‘at the mercy of settler majorities’, Russell argues. In all four nations, migration en masse combined with popular sovereignty, settler-colonial nationalism and a belief that governments knew how to assimilate people who were different, imposing a ‘common fate’. ‘The overall result of settler domination was basically the same’ in all four nations. However, sleeping treaties awake. The Treaty of Waitangi revived in relevance when New Zealand MPs wrote it into legislation in the 1980s as an aid to interpretation, an ‘adjudicative opportunity’ seized by that nation’s Court of Appeal. When Quebec stimulated attention to the Constitution of Canada, the Trudeau government was persuaded to recognise and reaffirm old Indian treaty rights; rights won in contemporary land claim settlements have since acquired the same constitutional protection. In the US, litigation about the scope of tribal sovereignty has yielded good results often enough to remind Indians of the value of a treaty tradition. In Australia, Russell concludes, ‘Mabo’s judicial victory’ has not been enough to overcome Australia’s lack of a legal and political heritage of negotiation.

None of the four nations has attained ‘a post-colonial condition’. Russell wants indigenous people to be integrated into their host nations as ‘operative political communities’ that enjoy a ‘collective right to equality’ within a shared legal system. ‘Native title’ was not merely a property right but a prompt to such political plurality (which the judges in Mabo and Wik declined to pursue). Russell’s vision of reconciliation implies that indigenous peoples must develop their own political institutions. Celebrating the political will of ‘the nationalist firebrand, Eddie Mabo’, Russell tends to treat as obstacles heroically overcome Mabo’s problems with political forms. However, his sense of the difficulties facing indigenous political mobilisation is clear when he remarks that in New Zealand it is not easy to identify ‘the Indigenous “self” that should be the bearer and beneficiary of Indigenous rights’. Similarly, he writes that ‘the cosmology and sociology of Aboriginal culture do not fit readily into structures required for making binding agreements with corporate and government bodies grounded in European traditions and operating on the basis of an imposed, an alien law’.

The problems of reforming indigenous political culture interest Russell far less than the possibilities and disappointments of the settlers’ political culture. ‘High Court juris- prudence cannot on its own accomplish decolonisation.’ Public opinion matters, for ‘decisions of high courts up- holding Aboriginal rights … will be ineffective if they go against the tide of opinion and outlook in the dominant society’. Chief Justice Brennan imagined public support for the norms that his 1992 judgment invoked. However, responses to Mabo and Wik were partisan, militating against the ‘consensual solutions’ required for native title to be appreciated and resolved as a constitutional issue.

‘Reconciliation’ could propel Australians towards a ‘broad consensual agreement on relationships with Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders’, were it not for the Howard government’s insistence on treating indigenous Australians as merely in need for socio-economic advancement. Russell holds the ever-popular John Howard responsible for the continuing partisan dynamic that afflicted the response to the High Court’s Wik judgment and for tapping nationalist resentment about international criticism of Australian policies.

Central to Russell’s learned, lucid and engrossing inquiry into his people’s liberalism is a question about the relationship of judicial and legislative authority in matters constitutional (in Russell’s widened sense of ‘constitutional’). Australia’s High Court, having invoked the best of the common law of ‘my people’, now ‘seems anxious to pass on to the legislature the primary responsibility for defining’ native title. One explanation for this faltering judicial heroism is that the judges have deferred to ‘a change in the political climate’. The other is that judges know the limits of the common law because they defer, out of constitutional principle, to law-making parliaments, the sites of popular sovereignty. ‘The basic axiom of settler society justice,’ Russell writes, is ‘that clear exercises of settler legislative authority extinguishing or encroaching upon native rights are not to be questioned by the courts.’ Were the common law rights elicited by Mabo’s litigation entrenched in Australia’s constitution, courts could better hold legislative authority accountable and so channel the colonial uneasiness of ‘my people’.

If constitutional reform is an important vehicle for matters ‘constitutional’, then we had better look beyond what ‘my people’ have done – to the Hispanic world. Since 1983, at least twelve Latin American nations have amended or written new constitutions in ways that honour indigenous representations of their needs and rights. Rich as the English settler experience may be, we must not assume that the Anglophone world holds all the historical lessons that we have to learn.

Comments powered by CComment