- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Giving voice to history

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

These two first novels are based upon events and people from Australian history. Noni Durack recasts the story of the pastoralists of the north-west of Australia in terms of an enlightened awareness of land degradation, but the narrative remains oddly captive to the legend of heroic conquest that she is trying to critique. Wendy James, on the other hand, has written an elegant feminist account of the lives of women in Melbourne at the time of the struggle for women’s suffrage.

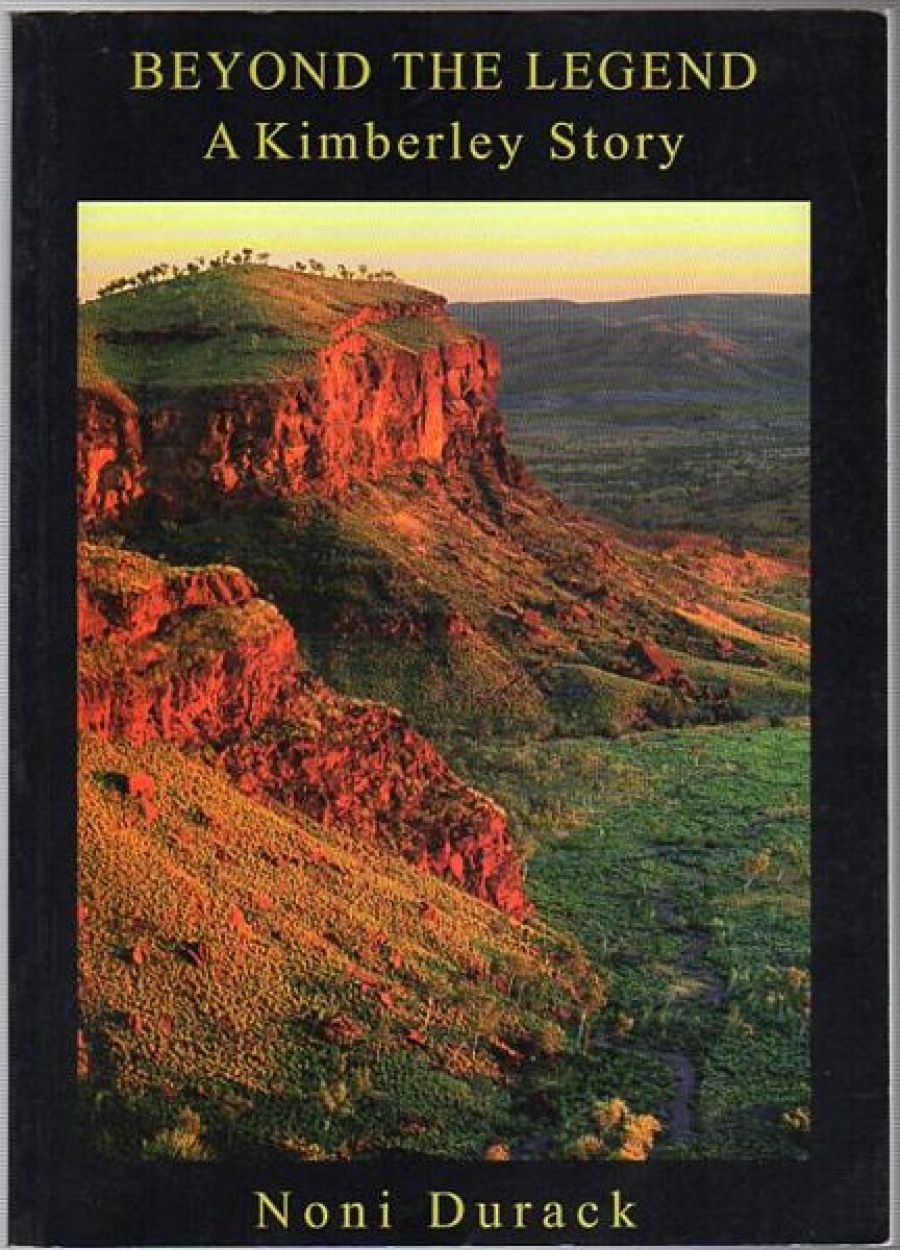

- Book 1 Title: Beyond The Legend

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Kimberley Story

- Book 1 Biblio: Central Queensland University Press, $25.95 pb, 221 pp, 187678072X

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

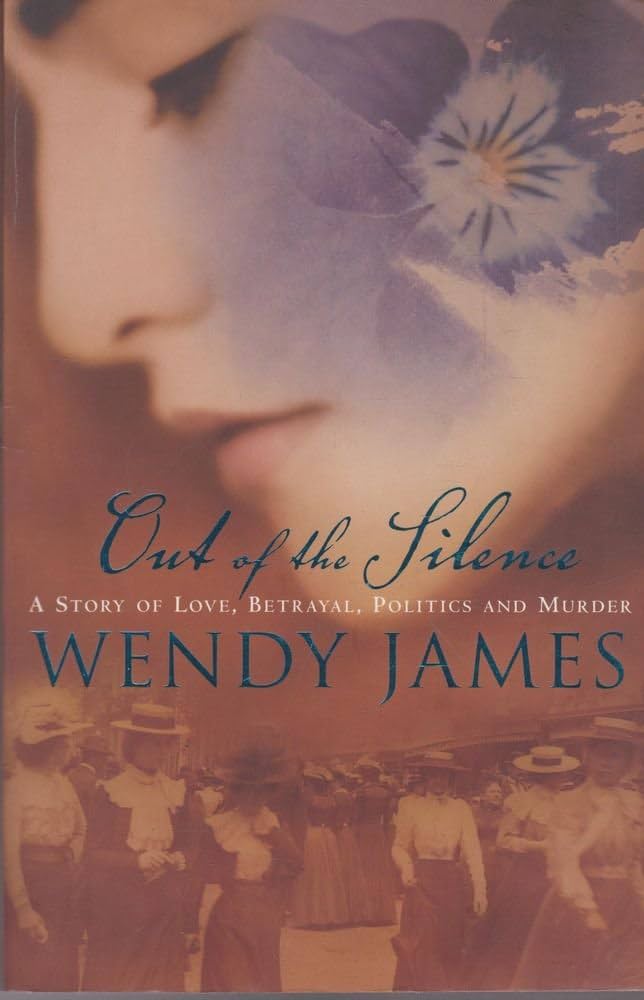

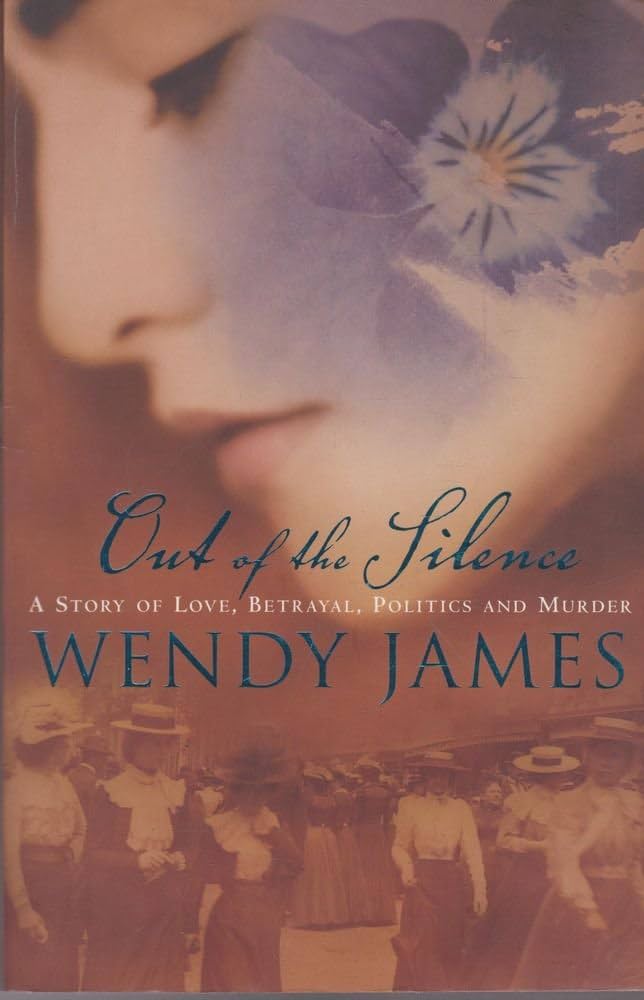

- Book 2 Title: Out Of The Silence

- Book 2 Subtitle: A story of love, betrayal, politics and murder

- Book 2 Biblio: Random House, $32.95 pb, 351 pp, 1740513835

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The main focus is upon the subjectivity of John, the first son of the third generation, and, to a lesser extent, upon that of his younger brother, Brian. John represents a new kind of heroic pioneer in the Kimberley, one who attempts to redress the long-term ecological damage caused by the huge cattle runs. The reclamation of the land using irrigation from the Ord River for intensive agriculture becomes John’s obsession. With Brian’s help – and that of an Aboriginal man, Horace, and an Irishman, Jim – John pursues with fanatical zeal his dream of a model farm. This story is the most compelling part of the novel and testifies to Durack’s assured knowledge of the region and her belief in ecologically sustainable development.

The novel’s good intentions, unfortunately, are undermined by a number of serious problems, some formal and some political. The first of these is the prose itself, indicating an uncertain grasp of sentence structure and punctuation. This makes the novel hard to read. There are also many uncorrected typos: Brian spelt ‘Brain’ quite often, and Japs, short for Japanese (which surely is no longer an acceptable term), spelt ‘Jap’s’ consistently.

By far the most glaring problem with the book, however, is its essentialist representation of Aboriginality: blacks are natural horse riders; ‘gins’ and ‘lubras’ giggle and shuffle cheerily around the big house. Durack’s patronising language might be understood as an evocation of white attitudes in the 1930s and 1940s, and an argument might be made that these comments appear only when the narrative is refracted through the characters. Perhaps, though this is far from clear. There is throughout a distinct paternalism to the commentary on race, always implying that Aboriginal people must be properly cared for by whites, but never assuming that they are equals. It is disconcerting that Durack just doesn’t get it about the natural rights of the dispossessed traditional owners:

When the structure of the stations was established each with its homestead and staff, stockmen, head stockman, manager, bookkeeper, cook most blacks fitted happily into its routine. The men, natural horsemen were quickly trained to handle stock and the women were helpful if often inefficiently so in the homesteads. It was a case of mutual exploitation. The whites exploited the blacks for their labour and the natives with their tribes of relatives, all fed by the station, exploited the whites in many devious ways.

Elsewhere, a character does concede that the land was stolen, but the above quotation is astonishingly blind to questions of prior ownership and to the disappearance of traditional ways of living for indigenous people. This awareness rarely enters the narrative and, when it does, it glimmers at the margins as its repressed unconscious. Full acknowledgment and development of these themes would situate the novel more securely within today’s understanding of the history of European land-taking. As it is, the politics of this book are well meaning about ecology, but confused about race.

Wendy James’s novel, Out of the Silence, is much more assured. Set at the turn of the nineteenth century in Victoria, mostly in Melbourne, its focus is the debate about women’s rights and the campaign to obtain female suffrage. Vida Goldstein is one of the subsidiary characters. There are two main characters: the working-class country girl Maggie and the upper middle-class Englishwoman Elizabeth, who lives in South Yarra in the house of Vida Goldstein’s aunt. The reach of this fiction is considerable; James writes about female sexuality and desire, pregnancy and childbirth and their consequences for women, especially for the unmarried. She also writes well about women’s domestic labour and employment, educational opportunities, the value of friendship, the effects of class, poverty, baby-care practices, and conditions in women’s prisons.

James evokes her period with the skill of an accomplished historian. She has managed some potentially awkward manoeuvres to bring forth the voices of her characters. In life rather than fiction, Maggie (who, we are told in the Author’s Note, is based upon a real person) would have been scarcely literate, but James effortlessly achieves an unforced first-person narrative for her. Maggie’s grim journey is convincingly charted from carefree country girl to sick and despairing inmate of Pentridge prison.

The alternating narrative dealing with Elizabeth’s story is represented in the educated language of a middle-class Englishwoman writing long confessional letters to her brother in America and making entries in her journal. She records her impressions of Australia and her excited but often amused responses to the lively debates she hears at her aunt’s dinner parties. Elizabeth’s private griefs about dead loved ones, her fears about the future and the pressing need to make a decent living are strongly evoked. In a neat parallel to Maggie, Elizabeth’s particular grief about her miscarriage of the baby she had conceived with her now-deceased lover deftly subverts middle-class prejudice about the moral laxity of servant girls.

James’s writing is noticeably informed by Australian women’s fiction about their experiences in a harsh and masculinist culture. Where Jean Bedford’s Sister Kate (1982) informs Maggie’s story, Barbara Baynton’s Bush Studies (1902) resonates behind the account of Elizabeth’s brief experience up-country as a governess. But the novel avoids gothic extremes in her return to Melbourne to teach in a girls’ school. The account of Vida Goldstein’s work for the vote is admiring but also conscious of the privileges that she enjoyed as an upper middle-class woman supported by a caring family. As Vida declares at a dinner party, she can make choices: ‘until a married woman is regarded “before all else”, as a human being, as Mr Ibsen puts it, until a woman can lead a dignified moral existence within marriage, I can do better – for myself as a well as others – if I remain unmarried.’

Elizabeth also sees that Vida’s unswerving dedication comes at a personal cost, one that she herself could not bring herself to pay. James’s descriptions of the dinner table discussions are the high point; headed in the narrative as ‘salons’, they have a considerable dramatic energy as all the characters, many of them male, discuss the issues of women and work, the vote and the politics of matrimony. This is an informative and beautifully written fiction.

Comments powered by CComment