- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: No mere pillion passenger

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

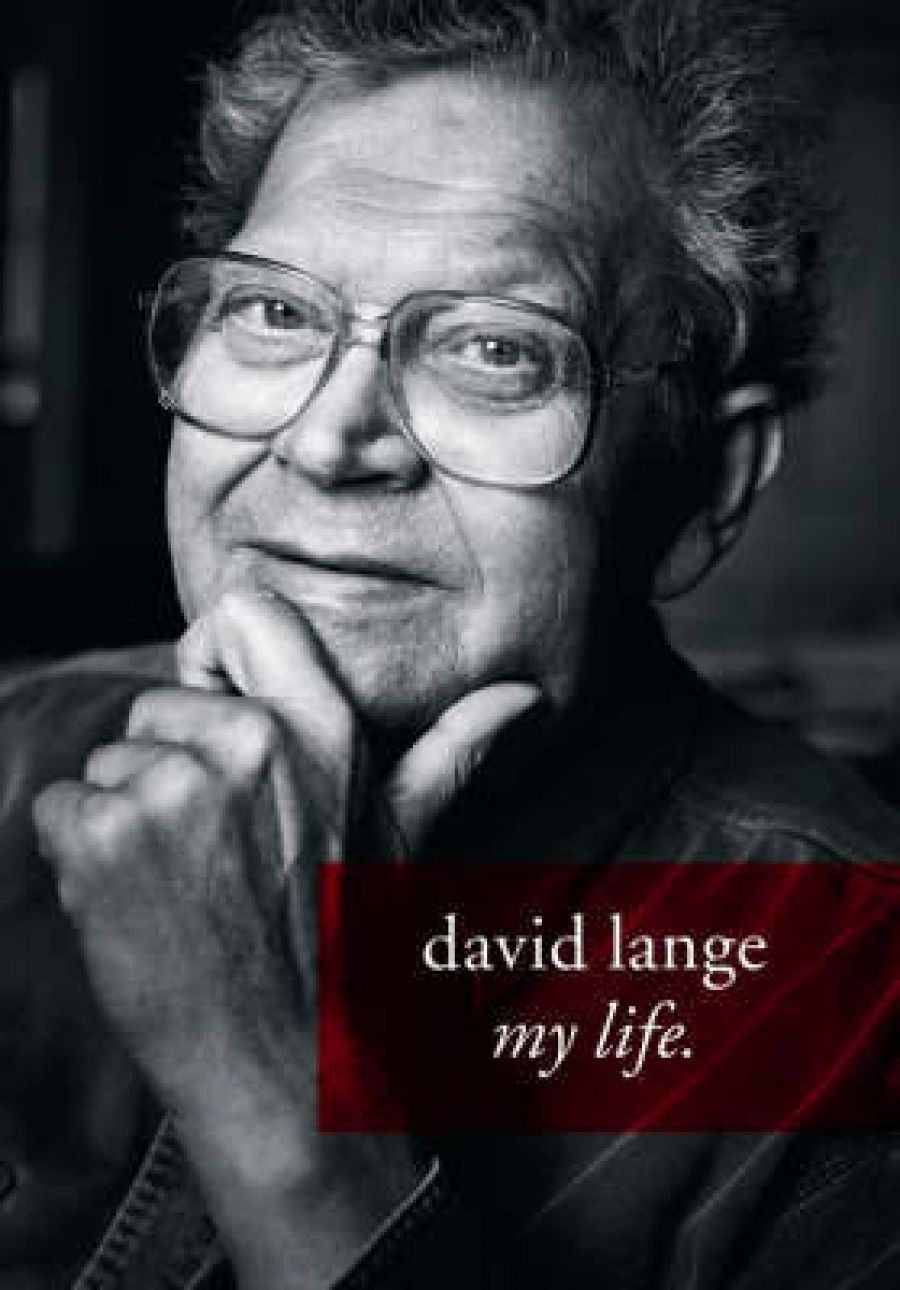

David Lange’s autobiography was published on 1 August 2005. Twelve days later, he died in Auckland, at the age of sixty-three, after kidney failure and a long battle with amyloidosis, a rare disorder of plasma cells in the bone marrow, having been kept alive by a pacemaker, chemotherapy, peritoneal dialysis, and blood transfusions. He had been a diabetic for many years. When My Life appeared, press reports concentrated on isolated paragraphs and sentences, containing critical remarks about his former ministers, and about Bob Hawke. The book could have been dismissed as shrill vituperation, but it is far more than that. My Life is a touching, searching and reflective work, deeply analytical and self-critical. David showed great courage in completing an autobiography so close to death.

- Book 1 Title: My Life

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $49.95 hb, 316 pp, 067004556X

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

There are obvious parallels between My Life and the controversial Latham Diaries. Both contain attacks on colleagues and were written during periods of disabling illness. However, the differences are far more significant. Lange was sustained by humour, had a wide experience of life outside politics, is able to understand an alternative point of view, was tolerant and humane, self-critical, a reconciler and undogmatic. Mark Latham conspicuously lacked those qualities.

I should declare an interest. David Lange and I had been friends since 1977. His size, infectious enthusiasm, wide range of interests and large appetite immediately marked us as soul mates. We communicated often and visited each other regularly, and I am generously treated in My Life.

David Lange was born in Otahuhu, an Auckland suburb, in August 1942. His father, Eric Roy Lange, was a medical practitioner; his forebears had emigrated from Bremen in 1865. His mother, Phoebe Fysh Reid, came from Tasmania. There were two boys and two girls. David’s childhood hero was Mahatma Gandhi, and he maintained a lifelong fascination with India.

David was educated at Otahuhu College, a state school. Because he was big and overweight, and the school produced outstanding athletes, he developed his verbal skills as a defence mechanism, and soon demonstrated a flair for spoken language. The trial (and acquittal) of his father on a charge of indecent assault of a female patient was a formative factor in his childhood, and he decided to become a criminal lawyer. He worked in a meat-freezing plant to support himself through Auckland University.

He wrote of his mother: ‘Mum slipped into Methodism with ease, although she could have settled into any number of churches. She was curiously catholic in her nonconformity. While the Methodist church was always her focus, any of the others were acceptable so long as they opposed drinking, gambling and acts of dancing on church premises, supported Sunday observance, and never challenged the literal interpretation of the scriptures … If she was nothing else, Mum was an exciting person to live with. What she did not offer in affection, she made up in activity.’

After graduating, David visited the Philippines and India, worked as an accounts clerk in London, and married Naomi Crampton. He joined Donald Soper’s West London Methodist Mission. Soper’s radical Methodism propelled David to membership of the British Labour Party, pacifism and activism with CND (the Committee for Nuclear Disarmament).

Lange returned to Auckland, took out an LLM, became a barrister and solicitor, and tutored in law for some years. From 1973 to 1976 he was also a pioneer of talk-back radio, using the pseudonym David Reid. He was elected to parliament in 1977 and became Labour’s deputy leader in 1979. He underwent a severe stomach stapling operation in 1981, which reduced his size dramatically. He explains, ‘I did not change my appearance in order to promote myself in politics – when I was a heap I did well enough in politics. I had the surgery because I wanted to live.’ But he did undergo a makeover in appearance, and this increased his confidence in parliament and his appeal to the electorate, especially on television.

Lange became Labour leader on 3 February 1983, the same day that Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser called an election in Australia and Bob Hawke replaced Bill Hayden as Opposition leader. Lange showed dazzling skills as a debater, able to inflict serious wounds on the National Party prime minister, Sir Robert Muldoon. He also benefited because a group of Labour MPs, including Roger Douglas and Michael Bassett, anxious to open up New Zealand’s closed, regulated economy, advocating the free market, decided that David – but not themselves – could win an election and give them the opening they wanted.

But Lange, like Latham, was oddly isolated as leader. As he looked around his Caucus, he wrote, ‘I saw supporters and opponents … I did not see enemies. Nor did I see friends.’ And he recognised that in 1983 he was not popular with the party rank and file.

Lange became prime minister in July 1984, Muldoon having called a snap election and campaigned badly. Muldoon failed to disclose the extent of New Zealand’s financial problems. These would have forced drastic change, whoever won the election. Lange’s government was compelled to devalue the currency, slash tariffs, deregulate the labour market, reduce government expenditure, sell public assets and introduce a Goods and Services Tax (GST). This Thatcherite transformation was known as ‘Rogernomics’, after Labour’s controversial Finance Minister Roger Douglas. Lange had increasing reservations about the social impact of restructuring and in 1988 made a pre-emptive strike against the introduction of a flat tax structure and further restructuring, forcing Douglas’s resignation.

Even before David became leader, Labour Party policy had been to exclude both nuclear-armed and nuclear- powered vessels from New Zealand ports. Helen Clark, then a backbencher, had been an architect of the nuclear ships policy. As Lange explained in Nuclear Free the New Zealand Way (1990), he would have preferred to exclude nuclear-armed vessels and to permit nuclear-powered ones. ‘The difficulty was that the United States … reserved the right to imply that every vessel in its fleet was nuclear-armed, from the oldest rust-bucket to the most sophisticated nuclear- powered vessels, which made the means of propulsion irrelevant.’ Although New Zealand did not formally withdraw from the ANZUS Treaty, it was effectively a dead duck by the end of 1984. Bob Hawke was very unhappy about New Zealand’s nuclear-free policy and offered much advice. Lange remarks: ‘He was steeped in the culture of mateship, which for me was never a good starting point.’

Lange writes movingly about the problems in his life, the breakdown of his first marriage, health concerns, increasing political unhappiness and ‘the anaesthetic effect of alcohol’. He remained in parliament until 1996, then dropped out of politics and the Labour Party, devoting himself to writing, public speaking (mostly paid) and making television documentaries. While David remained faithful to the culture of liberal Christianity, he drifted into the category of fellow traveller, shedding the discipline of church membership and, like me, becoming doctrinally shifty about core beliefs.

In 1992 he married Margaret Pope, in Glasgow. Their daughter, Edith, was born in 1996. ‘Edith has put up all her life with people mistaking me for her grandfather,’ Lange writes in his memoirs. After heart problems, major eye operations and kidney failure, David faced a death sentence in August 2002, with the diagnosis of amyloidosis. Kept alive by medical miracles, he found serenity and occasional joy, living a day at a time, with Margaret and Edith. He writes of Edith: ‘She looks after her mouse Salt and goes to the local school. I was never one for tucking my children up in bed and reading to them, but if I am lucky this evening Edith will read to me.’

Lange concluded My Life: ‘This year Auckland like me has had an Indian summer. I can see through my windows that the elm trees are shedding their leaves and that the ivy on the barn has reddened and will soon disappear. If I see its leaves again I shall be very happy.’ It was not to be.

Comments powered by CComment