- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: Raimond Gaita reviews 'The President of Good & Evil: The ethics of George W. Bush' by Peter Singer

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On the face of it, this book represents a strange project: to elaborate for the reader’s consideration the moral beliefs of a man whom the author judges (and judged in advance, one suspects) to be shallow, inconsistent, lacking moral and intellectual sobriety, and to have failed so often to act on the moral principles he repeatedly professes that he can fairly be accused of hypocrisy ...

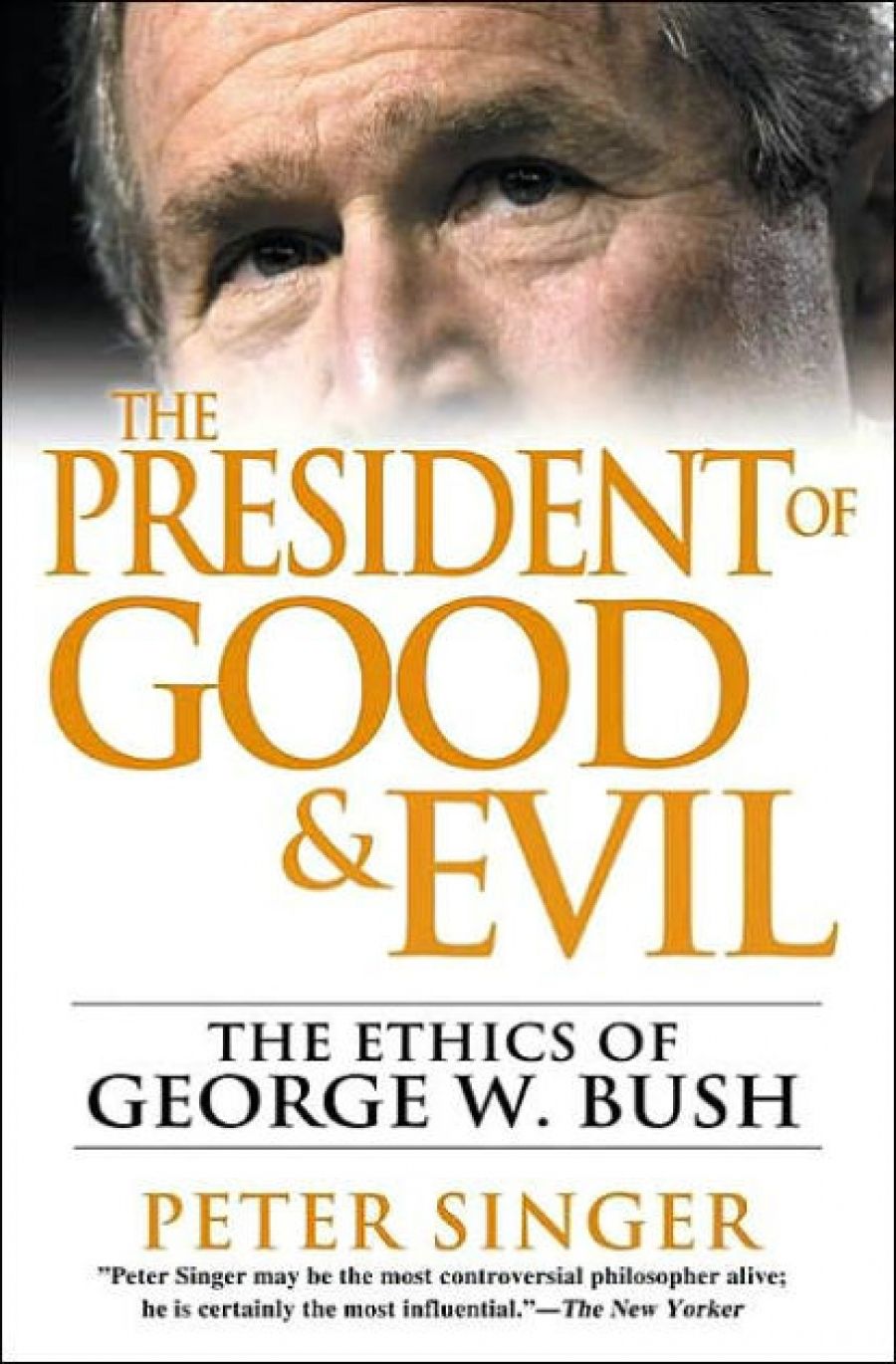

- Book 1 Title: The President of Good & Evil

- Book 1 Subtitle: The ethics of George W. Bush

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $30 pb, 303 pp, 1920885080

When he exposes, remorselessly, the flaws and inconsistencies in Bush’s moral beliefs, Singer takes the opportunity to explore matters that have been important to him for most of his philosophical life. Bush’s unsavoury satisfaction in the executions he sanctioned while he was governor of Texas, and his early determination to wage a war against Iraq, which no one could seriously say was one of last resort, lead Singer to mock the way Bush talks of the sanctity of life, and of good and evil. (Singer seems to take all talk of good and evil to be the expression of a simple-minded Manicheanism and a disposition to demonise wrongdoers.) On these matters, Bush is, of course, an easy target for urbane debunking. But a sign that Singer has even an inkling of how such goodness informs a sense of evil that, instead of demonising evil doers, insists that unconditional respect is owed even to the worst of them is not to be found in this book, nor I think, in any of his work.

It is hard to know whether Singer’s attachment to a narrow conception of reason, to what it is to be seriously reflective about one’s morality, and to his utilitarianism blinds him to possibilities in morals and religion, or whether his blindness to certain possibilities is the cause of his evangelical allegiance to those thin conceptions of reason and morality. Probably it is a bit of both. In this book, at any rate, one sees how each failing enables the other to flourish when Singer outlines what he believes to be necessary for inclusive, noncoercive discussion in a pluralistic democracy. We should, he says, ‘offer reasons that can appeal to all, not only to other members of our own community of belief. Otherwise there can be no public conversation that embraces the entire society.’ Concerned that the reasons for his attack on Bush’s kind of religious fundamentalism might be misunderstood, he says that ‘there is no reason of principle why claims about the existence of God and what he or she wishes us to do, should not be part of public political debate’. Later, he praises Aquinas and Anselm because they ‘believed that the existence of God could be proved by rational argument. Whatever we think of their arguments, at least they were concerned to justify their beliefs in terms of what we now call public reason. It is those who scorn reason who exclude themselves from the field of reasonable public debate.’

Note that division. On the one side, there is the kind of reasoning found in Aquinas’s proofs for the existence of God or Anselm’s ontological argument. On the other, there is scorn for reason. What is between? Sticking to discussions of religion, there are Augustine, Pascal (who urged that the heart has its reasons of which reason knows little), Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Wittgenstein (to name only a few), who thought hard about what it is to think hard about morality and religion. And, of course, there is art.

The starkness of the opposition is probably a slip, but it is a revealing one. If I understand him, Singer thinks that the forms of public reason necessary if political discourse in a pluralistic democracy is to constitute a ‘conversation’ are, in fact, just the kinds of reason necessary for moral reflection, period. Singer would, I am sure, acknowledge that there is much that should be taken seriously between the kind of philosophy found in Aquinas and the deep suspicion of reason that Luther expressed when he called it the devil’s whore. But he would insist, I think, that we need carefully to sift the genuinely cognitive elements from the emotive elements that often betray themselves in the style favoured by the thinkers I mentioned earlier. When they are released from their entanglement in emotive literary form, the cognitive elements will be presented for judgment before a court whose allegiance is to the kind of reason found in exemplary form in Aquinas and Anselm.

This thin conception of what counts as disciplined, rigorous thinking represents an indispensable part of our tradition. But it is only one part. Together with those conceptions that are opposed to it when it claims to be a prototype for all that is rigorous in thought, but which complement it when it assumes its proper place, it should be part of the content of our public conversation, rather than an arbiter of its form. Thinking about the death penalty (to take one of Singer’s examples), I might reread Camus’ or Orwell’s reflections on it. When I reflect on what moves me in their writings and what deepens my sense of what it means to face execution, my reflection will be answerable to a broader range of critical concepts than those that define Singer’s conception of reason. I will ask whether I have been moved because I am sentimental, for example, thinking of these not as deformations of feeling that cause deformations of understanding, but as themselves forms of the deformation of understanding – forms, in fact, of the false.

It is, I admit, a droll fantasy to imagine John Howard and Mark Latham arguing over what we might learn from Kierkegaard’s or Aquinas’s discussions of the parable of the good Samaritan in relation to our obligation to refugees. Even more droll is the thought that they might discuss what in politics should count as legitimate persuasion aimed at understanding and what should count as mere rhetoric, intended to hit below the intellectual belt. Yet they, as much as we, are moved by images and by edifying speeches, and should, as much as we, try to understand the difference between what is rhetorical in the pejorative sense of the term and what rightly moves us after critical reflection. Literacy in such matters should be a fundamental aim of the public education of citizens in schools and universities. Discussion of it in journals (such as this one) that occupy the intellectual public space between the academy and journalism should not be the rare thing that it is. If I am right, it is a profound irony that, for all his genuine concern for the nature of reason, Singer has acted more like the defender of a (rationalistic) faith than like someone who wishes seriously to inquire into the various ways we assess whether we are thinking well or badly.

Just as Singer tends to identify a narrow conception of reason with anything that counts as serious reflection, so he tends to identify a particular philosophical doctrine about morality (utilitarianism) with a serious regard in politics for the consequences of what one does or fails to do. Having argued (rightly, I believe) that Bush’s religiously based moral views are controversial amongst Christians, some of whom even argue that his beliefs and deeds are anti-Christian, Singer asks whether Bush is a utilitarian. To support the suspicion that he might be, he gives as an example of a ‘classic utilitarian justification’ Bush’s claim ‘that the great good of liberating millions of Iraqis from Saddam’s brutal tyranny justified the harm inflicted on a smaller number of Iraqis, even though many of them were innocent of any wrongdoing’. Later, almost unbelievably, he says that: ‘When Bush said, before his trip to Africa in July 2003: “We believe that human suffering in Africa creates moral responsibilities for people everywhere”, he might have been reading from a utilitarian textbook.’ Or, one might add, from Mother Teresa’s diaries!

From one perspective, offering those as reasons to justify asking whether Bush is a utilitarian is, again, just a slip, even if the second counts as a howler. But seen in the light of the fact that most of the ‘humanitarian’ justifications for the invasion of Iraq were indeed utilitarian, Singer’s slips encourage the amnesia (or plain ignorance) of the part of our tradition that taught that considerations deeper than utility must enter into an assessment of the moral character of our actions.

Singer appears to believe that until Jeremy Bentham outlined his doctrine of utilitarianism, the moral sense of humanity had been in large part distorted by religious superstition and by metaphysical muddle of the kind that reached a pinnacle in the (moral) philosophical writings of Immanuel Kant. That is why, I believe, that despite his admirable and some times courageous interventions in public affairs, despite his admirable gift for addressing a lay audience without the professional intimidation or even condescension that is sometimes found in the work of ‘practical ethicists’, and despite his eloquent appeal for citizens to converse rather than to try to overpower one another, Singer’s voice in this book is not altogether suited to such conversation. Too many voices are only partially audible to him.

Comments powered by CComment