- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Contemporary Classics

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Classics, like policemen, are getting younger. Pastures of the Blue Crane (1964) and By the Sandhills of Yamboorah (1965), the first two books reissued by the University of Queensland Press in their welcome ‘Children’s Classics’ series, are not those Australian children’s books (strangely supposed by many of my age cohort not to exist) that I read as a child, but the next generation, published in the mid-1960s when I was a young adult.

Thurley Fowler’s books were first published even more recently, in 1985 and 1991 respectively, but, like those of Reginald Ottley and Hesba Brinsmead, they are classics in that they breathe wonderful, idiosyncratic life into the people, times and legends that have helped to form today’s Australia.

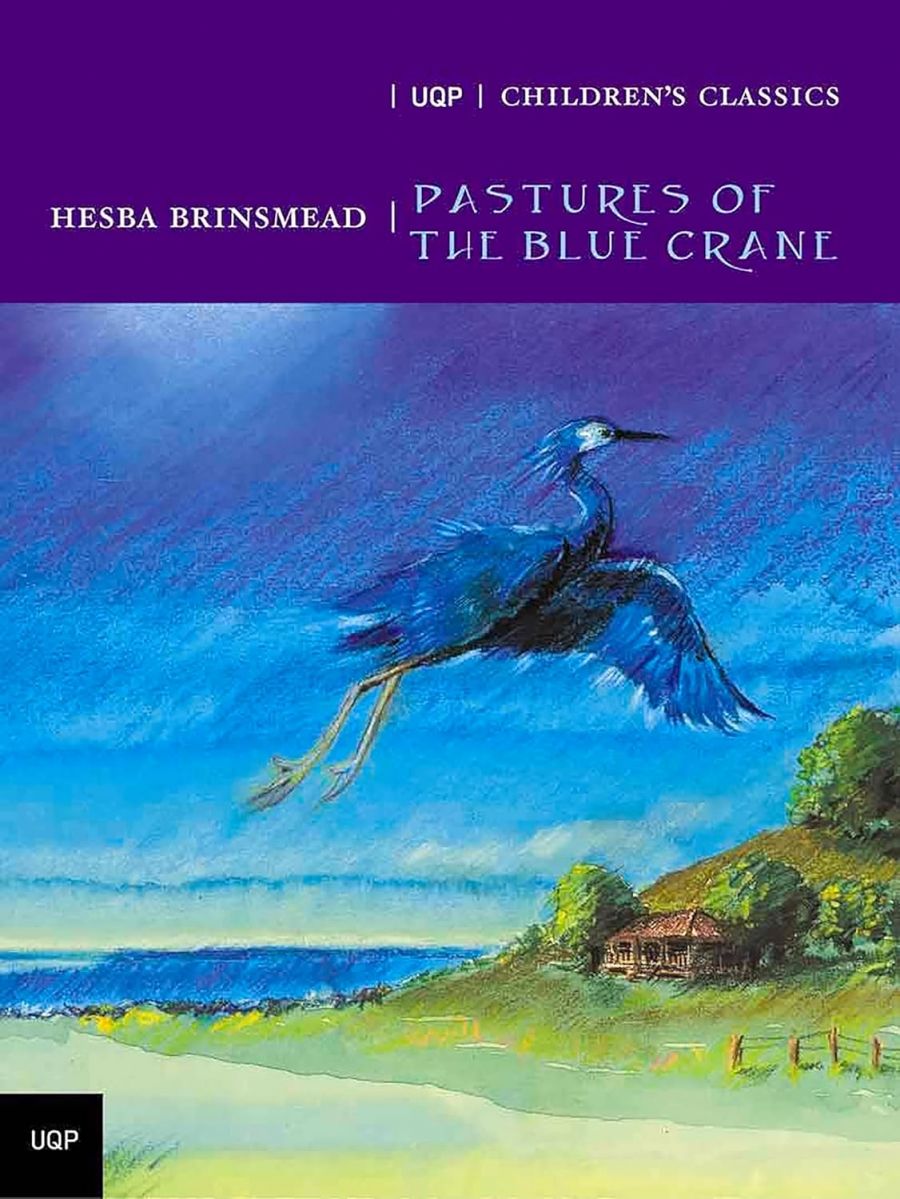

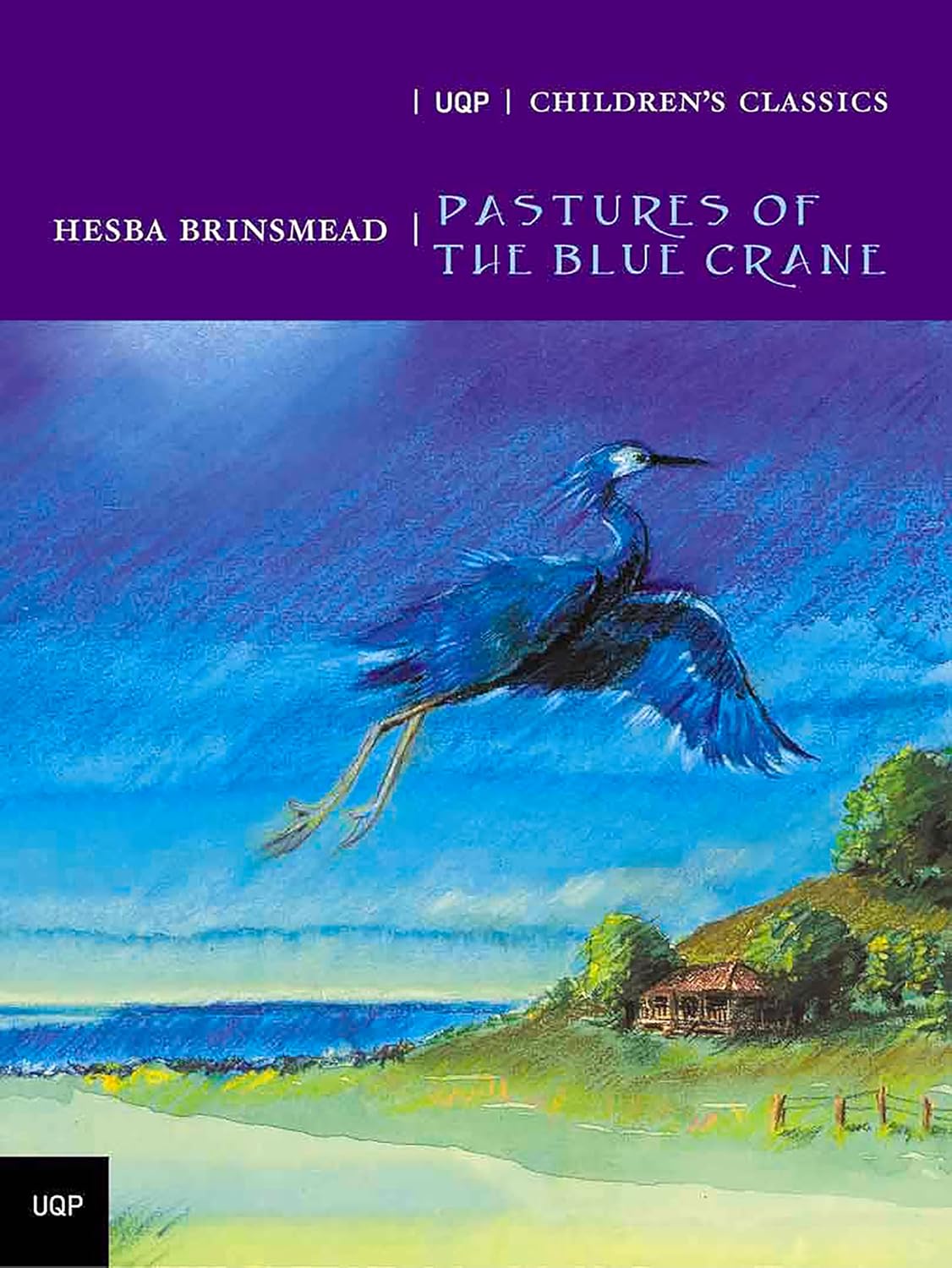

- Book 1 Title: Pastures of the Blue Crane

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $18.95 pb, 358 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

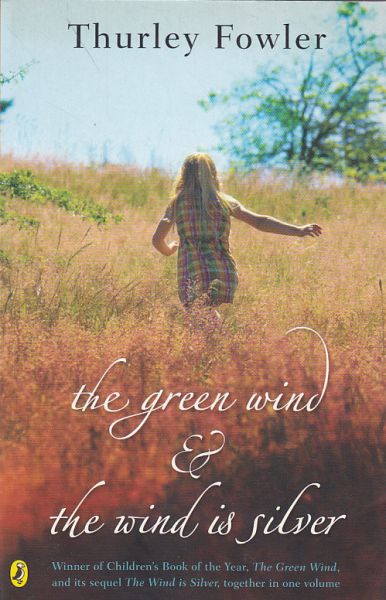

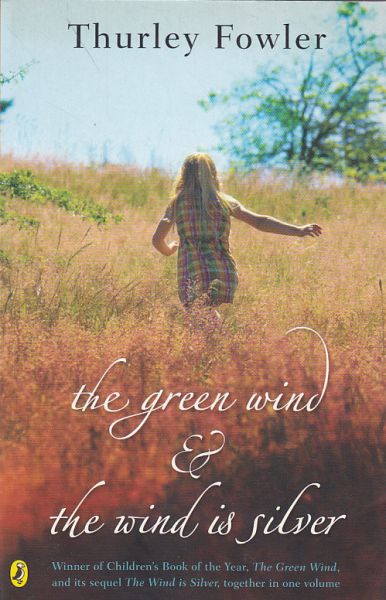

- Book 2 Title: The Green Wind and the Wind is Silver

- Book 2 Biblio: Puffin, $17.95 pb, 279 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

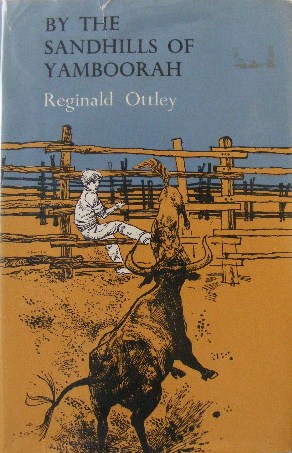

- Book 3 Title: By the Sandhills of Yamboorah

- Book 3 Biblio: UQP, $18.95 pb, 210 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

London-born Ottley ran away to sea at fourteen and at fifteen was working as a wood-and-water boy on a remote cattle station in the South Australian desert. Spare and reflective, redolent of extreme isolation and space, By the Sandhills of Yamboorah surely echoes this personal experience. The main character of the novel is known simply as ‘the boy’. His most intimate and sustaining relationship is with the dog Brolga and her one surviving pup, neither of which is actually his. The life of a busy cattle station goes on somewhere beyond the edges of his circumscribed existence, touching him when he is called upon to play a minor, apprentice role: helping with the butchering of sheep for the kitchen, tending the fire for the branding of half-wild calves, ferrying tools to the top of the windmill tower.

The boy’s regular rouseabout jobs leave him time to watch the sun set behind the scarlet sandhills and to ponder the anguish and poetry of life and death – the practical, unsentimental death of sheep, cattle and unwanted pups. and the tragic death of a dog who pines for her master. His thoughts are shared occasionally with the cook, the only woman on his horizons, who yearns a little over his youth and emotional self-sufficiency, or with the overseer who looks out for him in a casual, understated way; with the cheerful Aboriginal stockmen or with the swagman whose philosophy of perpetual motion he comes to understand and appreciate. Their varying adult attitudes are fleetingly canvassed, as are those of steely old Kanga the dogman, who, in his pragmatic relationship to the dog he loves, holds the boy’s happiness in his hands; who breaks the boy’s heart, saves his life and ultimately sacrifices his own prospects for the boy’s.

Ottley’s moving mix of personal experience, historical record and poetic, atmospheric description is set in the early 1930s, midway between the wars. Fowler’s lively family saga starts in 1948 and is crucially influenced by the father’s experiences as a prisoner of war.

The Robinson family – efficient, somewhat reserved mother; hard-working, empathetic, shell-shocked father; and four lively, individual children – leads a life of practical penury and imaginative plenitude on a NSW fruit block. The story focuses on Jennifer, a successful antipodean combination of Jo March and Anne Shirley, with her writerly aspirations and her redhead’s temper. When the story begins, Jennifer is an acid-tongued, accident-prone elevcnyear-old in her last year of primary school. Her entertaining scrapes rebound not only on herself but on artistic Margaret and sporty Richard, and even on her younger brother Alexander, with his inconveniently tender passion for the welfare of all animals, from the family’s chooks to the Ice Cream Man’s horse.

While The Green Wind (1985) and The Wind Is Silver (1991) form an entertaining rites-of-passage story of a rural family’s growth through adversity to maturity, they incidentally document a bygone era of ink powder and china inkwells, kerosene lamps, fuel stoves, washday coppers and unsewered outside toilets. Both novels are also concerned with the concept of courage: teenage Richard, mortified by his father’s war legacy of phobias and his extreme reactions to loud noises, extols the fortitude of a friend’s father who ‘misses not being able to shoot down planes’. Richard’s growing maturity opens him to a new appreciation of his father’s sensibilities and an understanding of different kinds and characters of courage, including his own in publicly embracing an unexpected career choice.

The end of The Green Wind leaves the reader hungry for more of the everyday adventures of the engaging Robinson family. While The Wind is Silver fills the gap satisfactorily enough, it is a less accomplished novel. The main characters remain strong and, to a certain extent, continue to develop. New concepts, such as battery farming, are interestingly introduced. But new characters such as the parasitic Ambrose Purple and the unhelpful Janet Oliver hardly rise above the level of caricature, and some enterprises seem far-fetched.

Hesba Brinsmead’s Pastures of the Blue Crane was bravely progressive for its time, but its stance on racial stereotypes is now deemed to require enhancement by an introduction that underlines its daring while also pointing out that writers ‘are always prone to pass on the unexamined values and modes of thought of the culture in which they live’. I am not convinced that the example that Clare Bradford, a children’s literature academic, uses to illustrate her contention is a legitimate one in the context of the novel.

Ryl Merewether was abandoned by her father at the age of three and raised in boarding schools. We meet her, at the end of her schooldays, at the lawyer’s office, where her father’s will is to be read. The occasion introduces her to a grandfather she didn’t know she had and to their joint inheritance: a dilapidated banana farm in northern NSW. The novel details Ryl’s blossoming from a cold, spoilt, desperately lonely schoolgirl into a vivacious young woman, with some faith in her own abilities, some empathy for others and a practical vision for the future. The changes are realistically wrought by the generosity of her new neighbours, by her developing relationship with her scruffy, crusty, congenitally economical and lonely grandfather, and, perhaps most of all, by the freedom and beauty of the surroundings in which she finds herself. Central to the humanising of Ryl is the influence of student and taxi-driver Perry Davis, a mixed-race descendant of Kanak labourers brought over to work the cane fields in the nineteenth century. As her friendship with Perry grows, Ryl moves from a position of automatic racial prejudice to respect, admiration and deep affection, sentiments upon which she is able to rely when the mystery of her own background is mooted and, eventually, staggeringly explained. Sadly, racial harmony and the breaking down of all kinds of racial and gender stereotypes have not advanced so far in forty years that Ryl’s lessons have become otiose. Today’s young readers could well accompany her on her journey to independence of spirit and openness of mind through the medium of this finely crafted, enjoyable and surprisingly contemporary novel.

Comments powered by CComment