- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Our Mrs Roosevelt

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

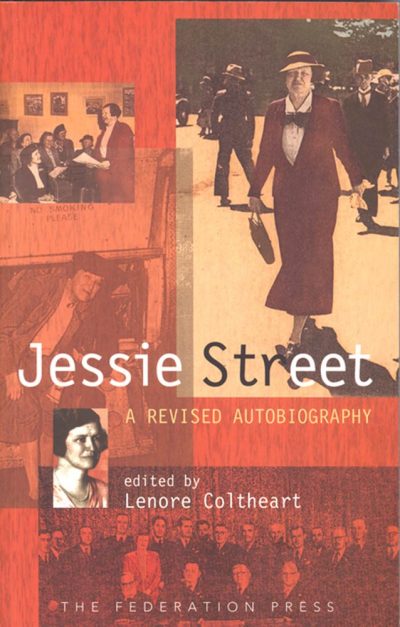

Jessie Street’s autobiography should be compulsory reading for anyone who seeks political change. In the dedication to her mother’s book, Belinda Mackay writes that she hopes ‘the women of today will be inspired by the spirit of Jessie Street and her visions’. To describe this autobiography as inspiring is an understatement. It is an extraordinary record of a remarkable life. Indeed, it is difficult to know how to explain Street’s immense contribution to women’s right welfare economics, social justice and peace studies.

- Book 1 Title: Jessie Street

- Book 1 Subtitle: a revised autobiography

- Book 1 Biblio: Federation Press, $30 pb, 246 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In 1941, when the Germans invaded the USSR, Street and her associates arranged to send supplies. Street recalls: ‘I called on three friends of mine – Lady Lakehurst, whose husband was the State Governor, Archbishop Mowll, and Supreme Court judge, Sir Percival Halse Rogers – to ask if they would accept nomination as patrons of the new organisation and all agreed.’ This new organisation was called the Russian Medical Aid and Comforts Committee, and by May 1942 it had raised £43,000. Most of the aid was used to send Australian sheepskins to the Russians. Street herself organised tanning facilities and travelled Australia, inspecting the skins to ensure they were weatherproof: ‘I used to soak them in the bath in my hotel room, and reject those that dried stiff as a board.’

Many of Street’s projects were organised with ease: she was a superb networker. But the cause for which she is probably remembered – her campaign for equal pay for Australian women – was tough and fruitless for many years. The lobbying began with the establishment of the United Associations of Women in 1929. In 1939 the Menzies government set up an inquiry into the basic wage. Street’s group briefed a lawyer, Nerida Cohen, to argue the case before the Commonwealth Arbitration Court, but not one trade union would make an application for equal pay at this time. Undeterred, Street and Cohen called together the thirty-three trade unions, which agreed to make an equal pay application to the Court.

Yet there were many more hurdles. In 1942 the Curtin government advanced the rate of women’s pay to seventy-five per cent of male rates. Employers challenged this legislation, which was upheld by the High Court, but only on the grounds that it was a wartime measure. The principle was still not enshrined, and was not accepted by the Arbitration Court until 1972. Street explains in her no-nonsense fashion that the resistance to equal pay was a function of the system of marriage under which women work for nothing and have no claim on the family income, despite the male wage being based on the need to support a family.

During World War II, Street initiated training for groups of women to defend themselves in the event of a Japanese landing in Sydney. As recreational rifle groups would not allow women to join, Street obtained a permit to acquire and use ammunition. After a short time, this permit was revoked. Frustrated with this decision, Street declares that she ‘resorted to a deputation to the Minister for Defence, Mr Frank Forde, who was a friend of mine’. A large group of women met Forde in his office to be told that cabinet ‘admired all that women were doing to help the war effort both in voluntary work in the Red Cross etc etc’. He continued: ‘But ladies, you don’t want to learn to shoot, to kill people.’ Street recalls her retort: ‘Well Mr Forde, we are learning to shoot to help defend Australia and protect ourselves from an invasion. But if you would prefer us to be defenceless and to be raped by the Japanese, well, we know where we stand. The matter is in your hands.’ The embargo on ammunition was lifted immediately.

Street not only worked at the grassroots level, but was also active internationally, keeping up contact with women’s groups in Britain and in the US in spite of the difficulties posed by distance. Invited by Prime Minister John Curtin to serve as a member of the Australian delegation to the conference setting up the United Nations in 1945, Street travelled to San Francisco with Ben Chifley, H.V. Evatt and another seventeen men on an RAAF bomber under cover of darkness, the journey taking some three days. The exhausting committee work that Street undertook at this conference, which lasted two months, is recorded faithfully, with close attention to the nuances of various Articles.

Jessie Mary Grey Lillingston was born in Bihar Province, India, in 1889 and was educated in England at the progressive Wycombe Abbey in Buckinghamshire. She convinced her father to allow her to study for a degree at Sydney University in return for ‘coming out’, something she had previously refused to do. After graduating she married Kenneth Whistler Street, later to become chief justice of the New South Wales Supreme Court. They had four children. Somewhat disappointingly, Street presents little more than factual material about her family in this autobiography, choosing to focus almost exclusively on her political work. As a result, every campaign is documented comprehensively in lively and economical prose. Street’s understanding of realpolitik and her dedication to social change are exceptional. Her compassion for the disadvantaged seems to have motivated her throughout her long and illustrious career. Jessie Street’s autobiography offers a history of the twentieth century from the point of view of an Australian woman of vision, commitment and rare political talent.

Comments powered by CComment