- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's and Young Adult Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Crackling Good Yarns

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In an era when so many young people seem to be cosseted and protected from anything harsh or dangerous, there are still good books to show them the darkness and complexity of real life. These three new titles are all emotionally and intellectually confronting, and none pulls any punches. In James Roy’s Ichabod Hart and the Lighthouse Mystery, convicts are deliberately mutilated to make them more efficient in the mines; in Peter Jean’s Stoker’s Bay, one character is flogged almost to death as a punishment for rape, and another is drowned with his hands bound; and in Jackie French’s Tom Appleby, Convict Boy, an otherwise light-hearted offering, there is a graphic hanging scene.

- Book 1 Title: Tom Appleby, Convict Boy

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $14.95pb, 224pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

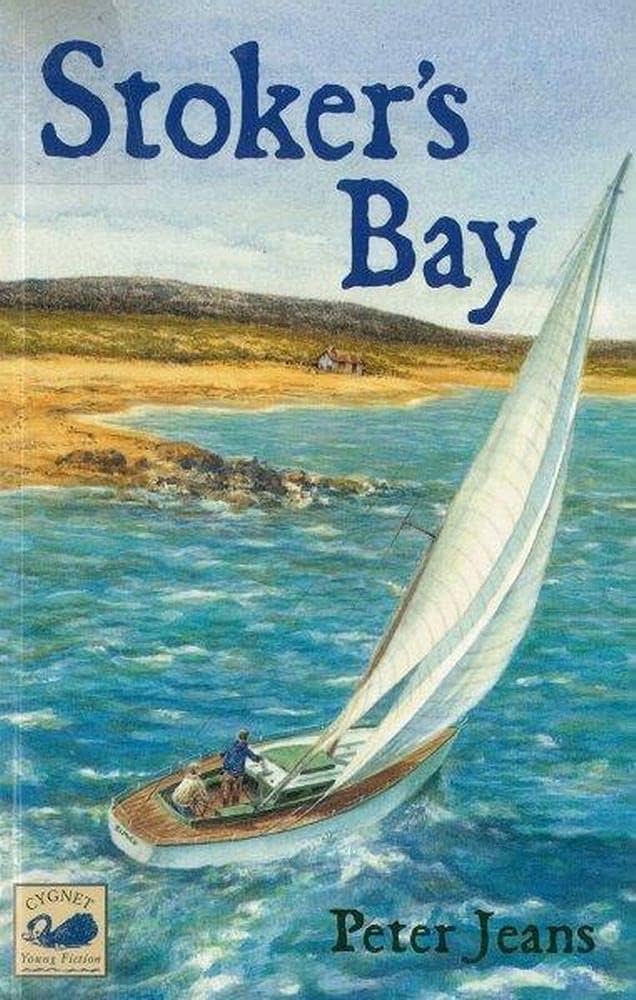

- Book 2 Title: Stoker's Bay

- Book 2 Biblio: UWA Press, $16.95pb, 240pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Ichabod Hart and the Lighthouse Mystery

- Book 3 Biblio: UQP, $18.95pb, 375pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

The year is 1901, and we are in the colony of New South Wales, but history has been slightly altered – we’re in a parallel universe. Author James Roy, in his sixth novel, has asked a few ‘what if?’ questions, and the Australia he delivers is just a little different from the real one. In Roy’s vision, New South Wales takes up the eastern half of the Australian landmass; the French have colonised the western side, along with Tasmania, and created an entity called Nouvelle Provence. These two hostile nations face each other across a strip of desert, an arid DMZ called the Exclusion Zone.

In Roy’s New South Wales, the principal city is Port Nelson, which he locates on the site of the real Nelson Bay. Sydney does not exist – only Port Jackson, a sleepy little market town about 200 kilometres down the coast. Convict ships are still arriving, and their cargo of desperate slaves – hollow-eyed, starving and often hideously mutilated – are building an empire. Port Nelson is a place of dirt, violence, poverty and danger. It is under martial law, with curfews and patrolling redcoats; rival gangs (the workers of the two great railway barons) battle each other in the streets.

Ichabod Hart, despite being an orphan, seems a happy eleven-year-old, oblivious to these unpalatable realities. He lives in a disused lighthouse with his foster father, a retired navy man he calls the Major. The kindly old man is an inventor who earns his living making whimsical little toys for rich ladies; he builds them pretty boxes that show moving pictures, and others that cast prisms upon the walls.

The plot thickens for Ichabod when, one day, the Major shows his wares to the wife of the richest and most powerful businessman in town, Mr Bowman, who immediately sees a use for the flashing lights that fits in with his deadly plans. Ichabod and his new friend Clementine (the Major’s niece) are soon caught up in Mr Bowman’s evil plot, which, with pluck and ingenuity, they help to foil.

Ichabod Hart is wonderfully imagined. Despite its darkness and the seriousness of its intentions, it is full of engaging humour. The plot rocks along in the best ‘ripping yarns’ tradition, with plenty of suspense. Roy creates vivid and fully rounded characters, particularly the two young leads. He is technically most proficient; the dialogue sparkles, and he handles several different accents and dialects with aplomb. It is in his richly imagined Other Australia that Roy really shines. His earlier titles, particularly Captain Mack (1999) and A Boat for Bridget (2001), have been awarded numerous prizes and honours: Ichabod Hart should be winning some of its own soon.

Another strange tale, which in a different way also explores the pull of the past, is Stoker’s Bay. In this case, though, it is one’s personal history – the secrets and hidden tragedies that can cast dark shadows on the present. In Stoker’s Bay, Peter Jeans has written a sequel to Badger (2002), the story of Angus McCrea and his dog, and it tells what happens when Angus is sent away to high school in a bigger town. The year is 1946 and the events are set in a fictional town on the coast of Western Australia, but the story could take place any time, anywhere.

Much of the book relates the story of an ordinary boy at a quite ordinary boarding school. He arrives at age twelve, and the terms roll on with very little excitement. Angus makes friends, eventually finds a girlfriend, and gets along well academically. A bully is vanquished, a geography assignment is completed, a dance is organised, and the reader wonders where the heck all this is heading. Then, suddenly, everything changes: a young man dies, and it does not look like an accident – at least not entirely. The last seventy pages or so are riveting, with real suspense. The reader does not know what happened, but we suspect murder, and we don t know whether to hope or fear that the murderer will get away with it.

Angus testifies at the inquest, and tells the truth, but not the whole truth – at least, he’s not wholly sure if it’s the whole truth. At the end of the book, he is still not certain if he did the right thing, and neither are we. He feels used, and not entirely sure that a major tenet of his moral code – ‘Never dob in a mate’ – has been appropriate for this situation.

Stoker’s Bay is a most interesting book, once it gets going, but its flaws almost derail it. For one thing, it is unclear just when the ‘now’ of the story is. Angus is looking back through time, but how much time? Sometimes his perspective is that of a young boy sometimes that of an omniscient adult narrator. The book also tends to tell, rather than show, such things a homesickness, friendship, kindness and so on. And it is doubtful that many readers, especially young ones, could bear the slow pace of the first 150 pages, which is too bad, because the ending – with the uneasy questions it leaves in the mind – makes the book well worth the trouble.

A most engaging look back at the first years of Australian settlement is Tom Appleby, Convict Boy. From the prolific author and wombat-lover Jackie French – this appears to be her 111th book – comes a tale of one of the First Fleet’s youngest passengers. Tom’s story is ably told in vivid flashbacks from the vantage point of his prosperous old age. Now the heart and soul of a large and loving family and the master of spreading acres, Tom reflects on those first adventurous years of his own and the colony’s life. Along the way, French clears up some mistaken ideas about that era, including the popular belief that there was widespread starvation. Tom’s story is fiction, but his tale is based on the experiences of several real people, including some of French’s own family.

Comments powered by CComment