- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Migrant Bildungsroman

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Novel, autobiography, memoir? I imagine poet and editor Manfred Jurgensen dealing impatiently with the question – does categorisation matter? Aren’t books to be judged by intrinsic worth rather than labels? Up to a point, but in Book One especially (of two) there is enough equivocation to be annoying.

- Book 1 Title: The Trembling Bridge

- Book 1 Biblio: Indra, $26.50pb, 341 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

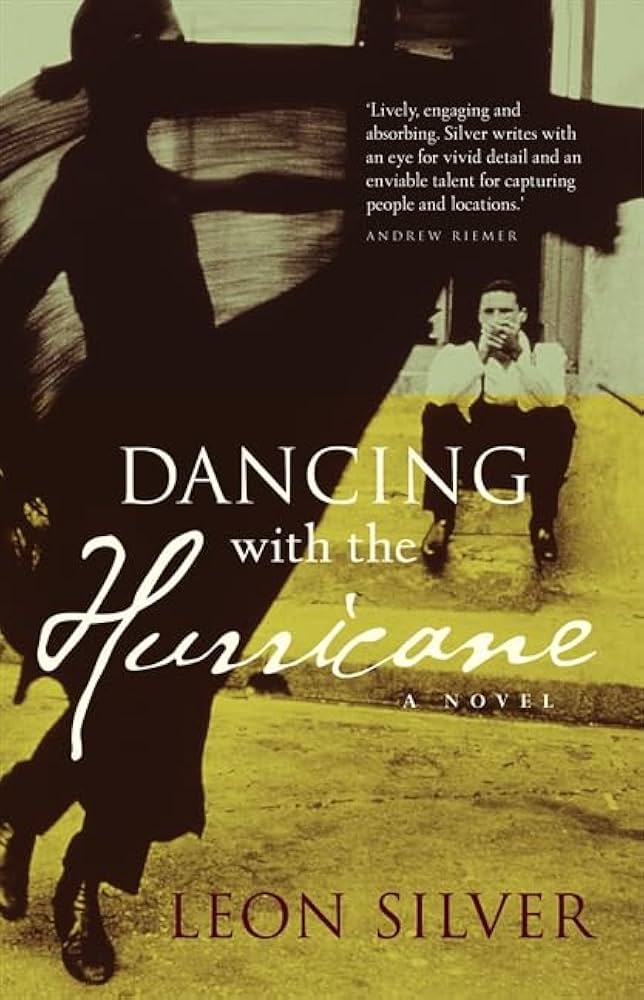

- Book 2 Title: Dancing with the Hurricane

- Book 2 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $27.95pb, 334pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

It is clear that ‘the war’ is not yet over, but, apart from claiming Mark’s father, it makes little impact on the town in which they live. Which is where exactly? On what ground? as Hamlet said to the gravedigger. The obliqueness of the narrative on this matter obliges the reader to turn to the equally reticent author blurb and do a bit of sleuth-work. If Jurgensen is of ‘Danish-German extraction’, and if a national border runs through the very harbour on which the unnamed town is built, then the general location must surely be Schleswig-Holstein, that wide Danish promontory annexed by Germany in 1864. The war is obviously World War II, and ‘the Beautiful Enemy’ the Allies – but why not say so? Because this is purportedly a work of fiction? ‘All characters are fictitious’, it says in the acknowledgments. One can’t challenge the assertion, nor can one shake off the conviction that Mark was not intended to be read as a pure figment of Manfred’s imagination. However, we collude in Jurgensen’s pretence, ignoring the shifting boundaries because the story is always likeable. Ironically, its enjoyment lies in the candid self-revelations of the engaging young Mark, which stand out in welcome relief from the coyness of the author.

The narrative continues along its Bildungsroman way until Hanna succumbs to a blood disease and Mark’s mother also dies, or perhaps is institutionalised. Book One ends with her being returned by the police; Book Two opens with Mark sitting in an aeroplane bound for Australia. Vital details are still lacking – is Mark eighteen or twenty-eight? What year is it? It would be pointless to nick to Jurgensen’s own date of birth, given that ‘all characters are fictitious’. Really? Even the student counsellor called Mr Priestley, who helps Mark enter Melbourne University? What a coincidence for any reader with a long memory – there used to be a real person of identical name in just that position.

But this is to skip ahead. Before he can get to Carlton, Mark has to put in time at Bonegilla. In the camp, the huts are stifling and dirty, and the inmates have already locked into the national cigarette-and-beer dependency. One poor woman drowns herself, but Mark, as always calm and fortunate, is inexplicably transferred to Melbourne, with ten quid and a letter to a trucking company. The day after his arrival, he rents a room, dismisses the trucking job, discovers the Clyde Hotel near the university and decides to study medicine. Mr Priestley enrols him in a pre-Med science course and finds him an administrative job on campus.

Mark’s indoctrination into various rites, from the St Vinnies meat raffle in the pub to Italian films in the cinema known as the Bughouse, followed by a spag at (the still existing) Genevieve’s, provides nostalgia for any Melburnian, and authentic local colour for readers further afield. He finds companionship, even a puddingy girlfriend, in a house shared by four female students; he forms a baffling relationship with the passionate but elusive Helen, and is awarded a (Commonwealth?) scholarship. He eventually moves into Newman College, amazed that a non-Catholic is made unconditionally welcome. Altogether it is a feel-good story that would risk sounding like a fairy tale did we not ground it in the factuality its author denies. Perceptive about the Lucky Country as experienced by an even luckier young man, it is an emblematic migrant-makes-good enjoyably lively read, especially when the myth-of-origin obfuscations give way to the engaging recreation of Carlton (incomprehensibly ‘at home to the Tigers’) and its institutions during the early (or is it late?) 1960s.

At a couple of points, notably Essendon Airport and the Café Scheherazade in St Kilda, the boy on the Bridge might have been found dancing alongside Leon Gold, the protagonist of Leon Silver’s novel Dancing with the Hurricane, who flees with his family from Danzig to Shanghai to Israel, and finally to Melbourne. But their styles could not be more different. Leon’s voice, the only one we hear, is perpetually haranguing, pleading with or berating his beloved uncle Fred, who has tried to commit suicide, or his girlfriend Rosa, who is threatening not to marry Leon, in a voluble mixture of Jewish humour and angst.

For all his vivid and precious memories of a high-spirited, happy boyhood among the orange groves of his spiritual homeland, there are things Leon has never dealt with. Migration, shunting from country to country, is a constant evasion, allowing him to avoid thinking about people killed in the Six Day War, how Mr Kozlofsky kept beating the woman who saved his life, and why he, Leon, once threw his pet turtle into a fire and let it bum to death. At the age of fifty-one, by the bedside of his dying uncle, in easy Australia, the stream of verbal consciousness that Leon cannot quell penetrates the unexamined past. Four months later, at his uncle’s grave, he is telling his uncle’s spirit what he has only now, with shock and disbelief, come to understand. The economy in Israel might be booming, but the human situation is very, very bad; the Arabs can just sit back and watch the Jews destroy themselves in a horrendous civil war led by the religious fanatics he calls the Froome. ‘The Froome will finish what Hitler couldn’t ... You were wrong about the second Holocaust, Fred. It’s not going to come from the Arabs, it’s going to come from us.’ A mere reviewer can only let such words stand; they are too terrible and portentous to need any gloss.

Comments powered by CComment