- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Faking it

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Judi Farr – one of the fourteen interviewees who appear in Terence Crawford’s Trade Secrets: Australian Actors and Their Craft – reflects on the unpredictable nature of performance, and on the way in which an actor can become so immersed in a role and so apparently truthful to the emotion of the moment that, contrary to what we might expect, the connection with the audience is broken rather than reinforced. ‘Sometimes,’ she says, ‘you can do a play where tears will be pouring down your face, but you haven’t really affected anyone.’ Wendy Hughes makes a similar point: she recalls having to cry for a scene in a Paul Cox film, and how she prepared herself by getting deeply into the mood beforehand. During the first take, the tears flowed, and everything ‘felt so real’. Then she went through the scene again, but this time she ‘didn’t feel it the same and didn’t cry as much’. When the takes were compared afterwards, Hughes was struck by the fact that the one in which it all felt ‘really real’ was not the best. ‘The other one where I was in control was better.’

- Book 1 Title: Aussiewood

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia's leading actors and directors tell how they conquered Hollywood

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95 pb, 294 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

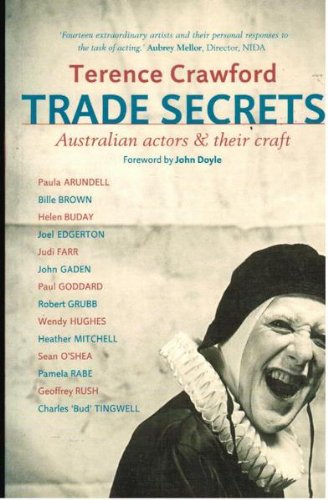

- Book 2 Title: Trade Secrets

- Book 2 Subtitle: Australian actors and their craft

- Book 2 Biblio: Currency Press, $34.95 pb, 228 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Books have and will continue to be written on the paradox inherent in these observations, a paradox that is central to the fascination the majority of us feels for the mysterious craft of acting. We cannot quite understand why the faked or acted emotion draws us in and helps us to understand the history and the complexities that sit behind it, whereas the ‘really real’ version may simply puzzle and embarrass us, creating an uncomfortable distance between the audience and what is taking place on the stage or the screen.

Farr and Hughes, and the other actors interviewed by Crawford, provide a range of such telling comments and anecdotes, in voices that are both spontaneous and directed at the same time. Some of the actors do, it is true, resist the efforts of the director to coax more of a performance from them. Helen Buday, for example, rightly described by Crawford as one of those actors with ‘something that makes them intrinsically interesting and magnetic’, does not quite enter into the spirit of the encounter, letting several of his questions pass with a nonchalant ‘Yeah’ or ‘I guess so’. Others – Bille Brown or Geoffrey Rush – need little more than a gentle prod to be off and away, leaving the question far behind as they riff entertainingly and illuminatingly on.

In all the interviews, the rather dutiful nods these professional performers make towards half-remembered theories of acting are outweighed by strong bursts of pragmatism and common sense, as if to counter the fear that probably besets most practitioners, that too much theory will kill the performance. ‘All acting is memory,’ says Brown gnomically. But when Crawford takes this as a cue to seek his views on ‘the whole Strasbergian experiments in Affective Memory’, Brown will have none of it. ‘Crap,’ he says briskly, as though waving garlic in front of a vampire.

The actor, who is paid to be someone else, must at the same time resist becoming someone other than himself. It is a dilemma to set the head spinning. ‘I became obsessed with my voice,’ recalls Joel Edgerton, who early on in his career began a complicated programme to correct what may have been a ‘very slight lisp’, in the hope that this would enable him to move more easily between characters. But he soon abandoned the process, deciding that his voice was him, slight lisp and all. ‘I have my voice,’ he says. ‘Who gives a fuck?!’

It is little wonder that these actors tend to downplay what is really involved in entering into a part, because of the worry that thinking too much, or trying too hard, or moving too far away from themselves, will paralyse rather than enable. The question remains as to whether this is a characteristically Australian approach to performance. Crawford admits in his introduction to ‘a nagging feeling that I’ve had for many years [that] Australian actors are making it up as they go along’. Rush seems to confirm this when he says that all you have to do to become a great actor is to do what children do naturally, ‘but a lot more, and with more finesse, and make sure you get a good agent’.

These kinds of questions would probably be easier to answer if it were easier to define Australianness. Michaela Boland and Michael Bodey’s Aussiewood: Australia’s Leading Actors and Directors Tell How They Conquered Hollywood is not very helpful in this respect. Peter Finch, whose name crops up at one point, is referred to for some reason as a ‘sometime Australian’, and poor Olivia Newton-John, given the briefest of walk-on roles, is chided for ‘famously travelling on a British passport’. Famously? On the other hand, interviewee Nicole Kidman is implicitly congratulated for having the career foresight to be born in Hawaii, thus making it easier to work in the US when the time came to try her luck, while Anthony LaPaglia is similarly complimented for his quick-wittedness in creating an entire American biography for himself, in order to win the part of a kid from Chicago in a television film about the mobster Frank Nitti (a tale that LaPaglia tells with amusing self-deprecation).

Whatever the nature and extent of their Australianness, each of the twelve actors and four directors who are interviewed in Aussiewood has something of interest to say about the phenomenon of Australian success in Hollywood, to the extent that Boland and Bodey’s hectically demotic style allows them to say it. The participants range from Paul Hogan, who has made an entire career out of his nationality, to Amanda Rogers, who changed her name very early on to the improbably euphonious Portia de Rossi and went on to perfect the walk and the talk, thereby landing successive and successful gigs on the American series Ally McBeal and Arrested Development.

For Heath Ledger, being Australian meant that he never seemed to be trying too hard. He always knew he could come home if it didn’t work out, and that helped him to appear relaxed under pressure. (Naomi Watts, by contrast, is eloquent on the dangers of being too obviously eager for the part.) Philip Noyce thinks that the reason we do well in the US is because we are similar but different. ‘You can easily connect with Americans but you’ll always see a situation differently.’ But it’s LaPaglia who seems nearest to the view that emerges more coherently from Trade Secrets. For him, Australian performers have an edge because, unlike their American counterparts, they don’t ‘over-think shit’. They simply get on with it. Of course that could be true, but then again it could be part of the act.

Comments powered by CComment