- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Ignorance is bliss

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The federal government maintains that it has no obligation to monitor the fate of non-citizens removed from Australia’s shores. In fact, it argues that it is better not to monitor returnees, since surveillance by a Western government might put them at greater risk. In certain circumstances this may be true: in a theocracy such as Iran, for example, where the very act of leaving renders a citizen suspect. In the main, however, the government’s argument is self-serving. The fate of Australian citizen Vivian Alvarez Solon, left to decline slowly in a Philippines hospice, shines a more revealing light on policy. It shows that Australian authorities have cultivated a determined indifference to the fate of deportees on the basis that ignorance is bliss. No care, no responsibility.

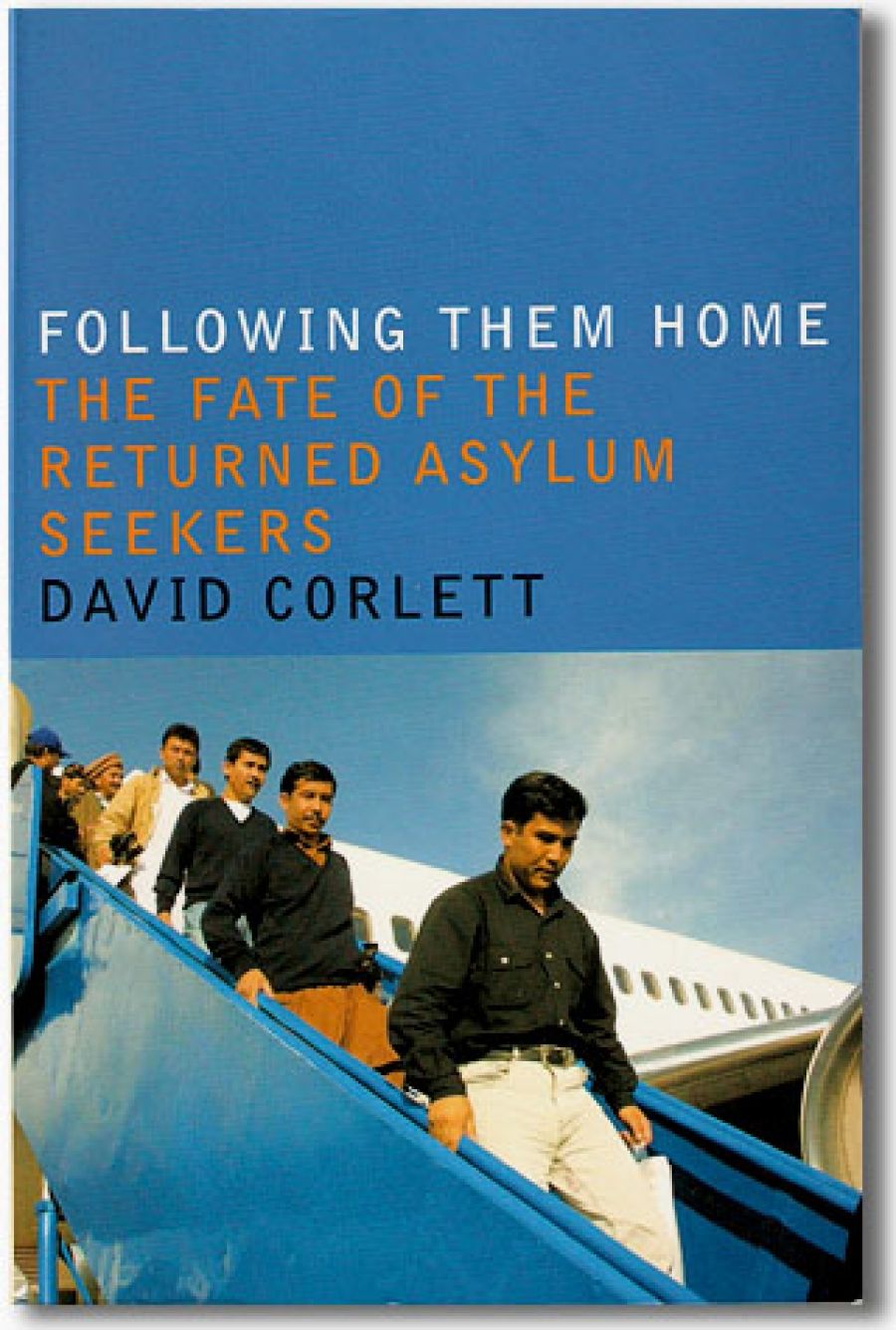

- Book 1 Title: Following Them Home

- Book 1 Subtitle: The fate of the returned asylum seekers

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $24.95 pb, 222 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

David Corlett refused to accept the government’s argument. He has made a major contribution to public debate by following returned asylum seekers home – though, as we soon learn, ‘home’ is often a misnomer. His travels take him mostly to Afghanistan and Iran, and his findings are shocking and disturbing.

There is the case of Aminullah, who reluctantly agreed to return to Afghanistan rather than remain in Baxter detention centre but who was denied a passport by the Afghan Embassy in Canberra. Instead, he was issued a twenty-day travel document by Pakistan, so he flew there (without the $2,000 ‘voluntary return’ money offered to Afghans by the Australian government, since he was not considered an Afghan national), crossed the border into Afghanistan, stayed in his hometown in Ghazni for six months and, finding no future there, returned to Pakistan, where he now lives without papers. Australia, Corlett writes, ‘willingly sent a man to a country where he was not a national, had no long-term prospects and no right to be there, and where it was highly likely that he would spend his days being harassed’.

Three young Iranian men – Amir, Reza and Shapour – tell remarkably similar tales of their separate returns to Tehran. Each was taken to a small room at the airport and interrogated for several days by officials, who they presumed to be intelligence agents. Their release necessitated a surety (in the case of Amir and Reza, it was the title deeds to their parents’ homes, in Shapour’s case a bond paid by a friend) and they were required to report regularly to the authorities. The experience of another young man, Mohsen, was even worse. He was imprisoned below the airport for forty days and brutally tortured. Despite, or perhaps because of, their experiences, almost all the Iranian returnees Corlett encounters are determined to leave Iran once more, though they are now heading to Europe.

Then there is the story of Mr Al-Khateeb, a Palestinian who grew up in Syria, but who cannot return there because of his past association with the ‘wrong’ faction of the PLO. Australia’s response to the problem posed by Mr Al-Khateeb was to shift it offshore. With official connivance, Mr Al-Khateeb managed to secure a visitor visa for Thailand and so went from detention in Australia to a life of limbo in Bangkok.

Corlett is courageous – not only in travelling to Afghanistan and Iran – but also in attempting to provide a balanced and clear-eyed account of the discomfiting stories of two of Australia’s high-profile asylum-seeker families: the Bakhtiyaris and the Kadems. These cases have divided opinion and aroused passions, and have become emblematic of key issues in the asylum-seeker debate. Neither family fits the idealised image of the refugee as a passive, innocent victim, eternally grateful for whatever crumbs of compassion fall from the Western table. The Bakhtiyaris and the Kadems are assertive and angry; their claims for refugee status are messy, complex and ambiguous.

Corlett begins Following Them Home with the Bakhtiyari story. The question of whether Ali Bakhtiyari was an Afghan farmer or a Pakistani plumber became front-page news in Australia as journalists ventured off to his putative home village in search of the truth. Corlett opens up the possibility that Ali Bakhtiyari was both: he believes that Ali’s father owned land in Afghanistan and that Ali worked that land at some stage, despite spending much of his life in Pakistan. After all, ‘movement of people between Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran is extremely common’. Corlett concludes that Ali’s wife, Roqia, was born and grew up in Afghanistan, but he leaves open the question of where their children were born and raised. He notes, however, that their son Alamdar certainly ‘feels strongly that he is an Afghan and is perplexed at suggestions to the contrary’. Corlett is able to assemble some evidence that the family has returned to Afghanistan, although this is far from conclusive.

Having begun Following Them Home with the Bakhtiyaris, Corlett closes the book with the Kadems. In this case, there is no doubt as to where the family has ended up – they are living a perilous existence amid the bombs of Baghdad. But to describe the family as ‘Iraqi’ is to oversimplify. Abdul Hussein was born and grew up in Kuwait, which is where he and his wife Ban were married, and where their four eldest children were born. After Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, the family was forced into exile in Iran. Their status there was increasingly tenuous and eventually they were tempted to risk the journey to Australia. The Kadems became notorious as ‘troublemakers’ in detention; they were involved in protests, including some incidents of violence, and engaged in acts of self-harm. Abdul Hussein was also convicted as a people smuggler; the court found that he had acted as an interpreter for a smuggler, who in return promised to reimburse the family’s fare to Australia (an amount of $8500). One son, Mohammed, developed a psychiatric illness and a serious drug habit, which led him into trouble with the police.

As Corlett writes: ‘There are no angels here.’ His portraits of the Bakhtiyari and Kadem families do not necessarily endear them to us; at times, they may have been their own worst enemies. But Corlett’s retelling also leaves us in no doubt that these families’ problems have been unduly magnified by their experiences in Australia. Their stories illuminate the central thesis of Following Them Home: that we have an ongoing obligation to people who have ‘been damaged, probably irreparably, by Australia’s asylum seeker policies’, whose ‘emotional and psychological destruction’ took place in Australian detention centres. Corlett is not arguing that no one should be removed from Australia and returned to their homeland. He is acutely aware that if the Refugee Convention fails to discriminate between refugees and others, then it becomes an open door for any migrant. However, he calls for Australia at least to offer ‘complementary protection’ for displaced people who may not fit the technical definition of a refugee, but who, in good faith, cannot be returned to distressed states such as present-day Afghanistan and Iraq, or who, for reasons beyond their control, have no other place to call home. And he makes a compelling case for further reform of the immigration detention system. If we inflicted less damage on non-citizens, then it might just be possible to send them home with less coercion and greater dignity.

Comments powered by CComment