- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The tragedy of Israel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The tragedy of Israel is that it wishes, simultaneously, to be a liberal democratic nation, one whose citizenship is defined by universal norms, and at the same time a Jewish state, where even Palestinians born within the borders of the country are denied full equality. I still remember my unease when I visited Israel many years ago at being asked when I, a secular Jew, intended to ‘come home’.

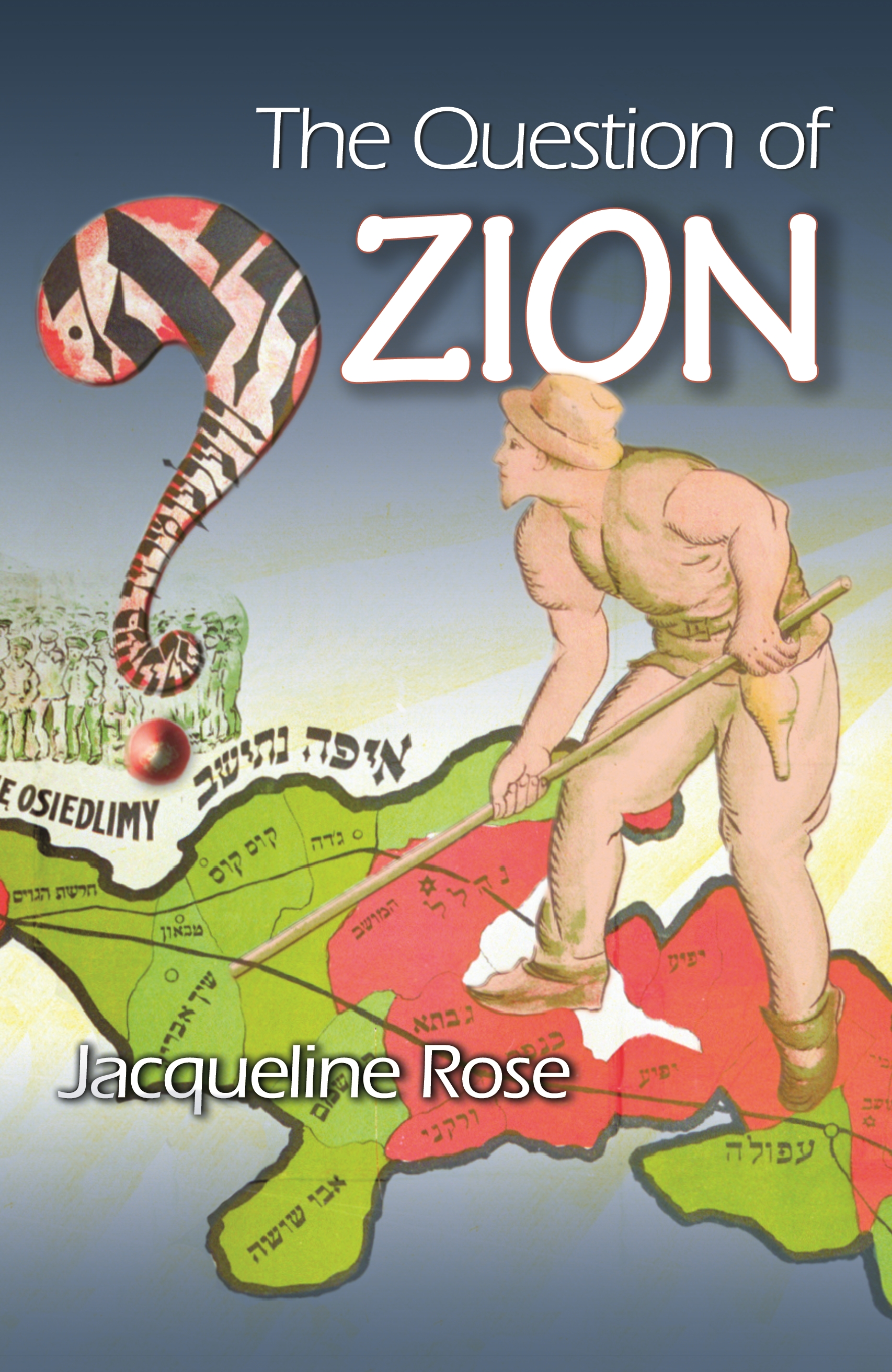

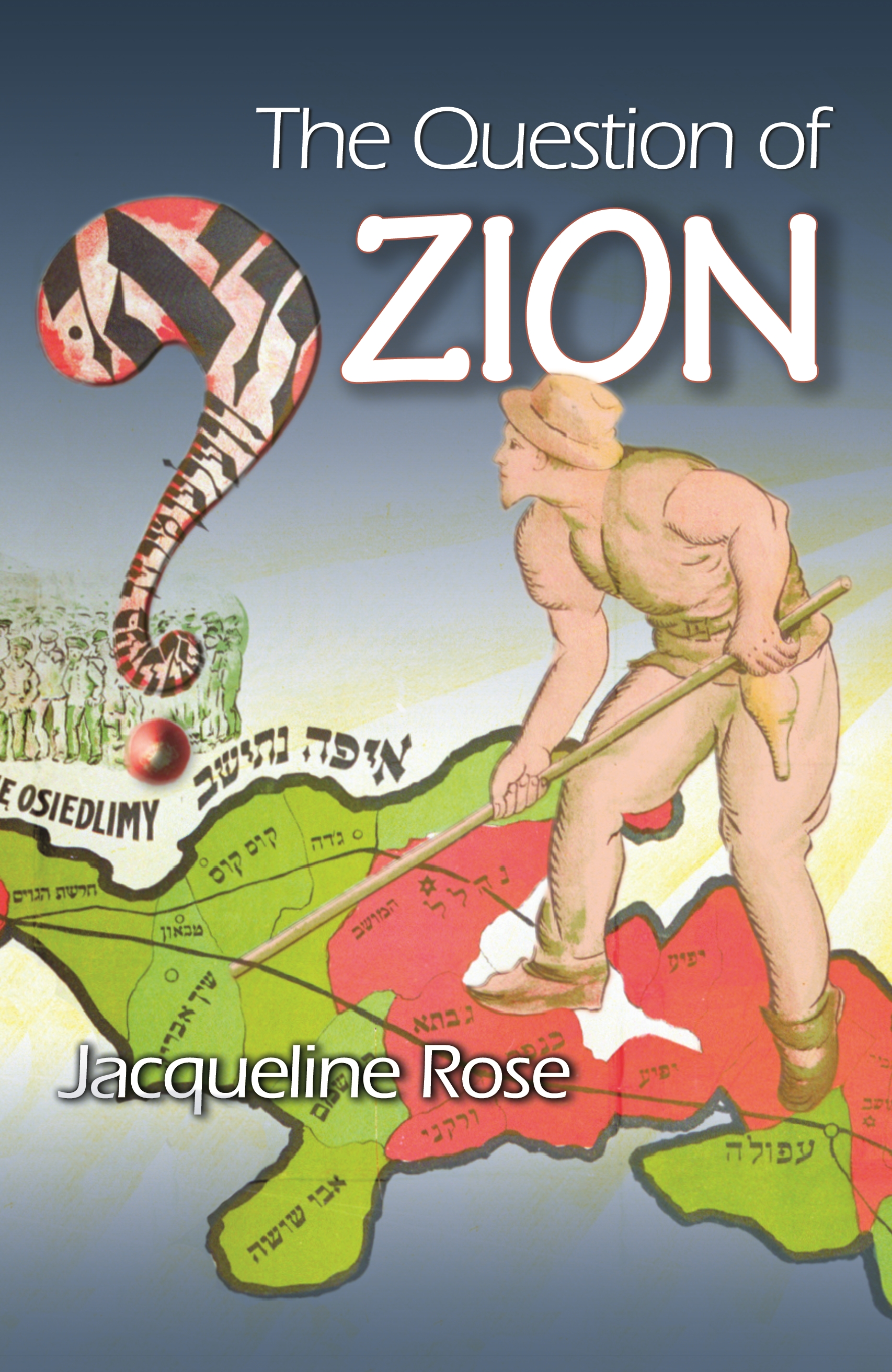

- Book 1 Title: The Question of Zion

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $24.95 pb, 232 pp, 052285219X

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Jacqueline Rose would share this disquiet. Indeed, she quotes one of the most famous anti-Zionist Jews, Hannah Arendt, who wrote of Zionism’s founder, Theodor Herzl, that: ‘He did not realise … that there was no place on earth where a people could live like the organic national body that he had in mind.’ Israel was founded on the basis of a romantic nineteenth-century notion of nationalism, the very version of nationhood, Rose points out, that Jews had to flee.

The strength of Rose’s book is that she uses psychoanalytic tools to probe the deep inconsistencies and unquestioned assumptions of Zionism. In this she draws on a thorough knowledge of the founders of Israel and their early critics, who, in ways that were remarkably prescient, foresaw the conflicts a Jewish occupation of Palestine would unleash. Those who note a frightening lack of reality in the Israeli perception of the world will find Rose’s careful analysis particularly useful, and her introduction to figures such as Hans Kohn and Ahad Ha’am (Asher Ginzberg) an important corrective to the simplistic picture most of us, Jews and non-Jews, have of Zionism. That she complements this with interviews with contemporary Israelis adds a particular concreteness to her argument.

Zionism is itself a complex ideology, child of both European anti-Semitism and the national romanticisms of the nineteenth century. ‘How,’ asks Rose, ‘did one of the most persecuted people of the world come to embody some of the worst cruelties of the modern nation-state?’ The Jews who settled in Palestine, and then supported the establishment of the state of Israel, knew this was no terra nullius, that they would displace large numbers of Palestinians. They were not unaware of the irony that in the name of justice for the Jews they were perpetuating injustice against the Palestinians. Yet even to write this is to risk being attacked as anti-Israeli, even anti-Semitic.

For many Jews, any attack on Israel is an attack on all Jews, and thus political criticism of Ariel Sharon becomes conflated with anti-Semitism, even when, as in the case of someone like Noam Chomsky, the critics themselves are Jewish. Rose explains this in terms of the shame around the Holocaust felt by many Jews. Shame seems an odd term – is it not, rather, the Germans and their collaborators who should feel it? – but it is a shame felt both by those who survived and by those who did not do enough to save the victims of Nazi policies. For Rose, the humiliations acted out daily against the Palestinians represent the classic psychoanalytic principle of repetition, where this shame is denied through aggression against others.

Most of today’s Israelis are born in Israel, and their claim to nationality is that of all of us who claim identification with the country of our birth. For Israel to become a ‘normal’ state, it will need not only to come to a genuine understanding with a Palestinian state, but also to accept that non-Jews born in Israel are equally Israelis, and that Jews (the majority) who continue to live in the Diaspora should not be expected to view Israel as other than another country. The messianic claims for a greater Israel, expressed by the fundamentalist settlers on the West Bank and Gaza (speaking all too often with American accents), are as destructive of Israel’s chance of survival as are Palestinian suicide bombers.

Perhaps messianism was an inevitable part of the Zionist project, even though many of the original Zionists were determinedly secular. Without the belief that they were fulfilling a divine mission, could a small number of settlers simultaneously have built a modern industrial state and created a military powerful enough to hold off far larger forces? After all, Chaim Weizmann, who would become Israel’s first president, declared in 1914: ‘If we were normal, we would not consider going to Palestine, but stay put like all normal people.’ This, of course, was long before the Holocaust, which gave the emotional and political support needed to win international, but particularly American, support for the establishment of Israel. Rose is interested, however, in the internal contradictions of Zionism rather than larger geopolitics, and she demonstrates that the apparent divide between secular and religious Zionists is not simple, further confused by those Orthodox Jews who reject Zionism as a political principle altogether.

This is a powerful book, written by someone who shares with many other Jews a sense of outrage ‘at what the Israeli nation perpetrates in my name’. One gets an insight into Rose’s feelings from her characterisation of the three chapters of her book as ‘vision’, ‘critique’ and ‘violence’. The Question of Zion is not an easy book to read; it requires some pre-existing knowledge of the history of Israel and it is written in an overly academic language that will keep it from those who most need to read it. Rose might retort that such language is inevitable if one deploys a psychoanalytic reading, but it is worth remembering that Freud at his best was capable of simple and elegant prose.

In the 1930s, there was a tentative move to establish a Jewish homeland in the Kimberleys, a move supported by the state government but opposed by many Australian Jews. There were other suggestions for a Jewish state in Uganda. Had either of these eventuated, the claims for a land based on biblical prophecies would have collapsed, and Israel might have indeed become a nation like all others. For Australia, there is a fascinating utopian novel to be written of what such a settlement might have meant. As the promoter of the scheme, former Bolshevik Isaac Steinberg, recognised, it would have avoided the pitfalls of nationalist fervour, and what he referred to as the ‘fanatical love’ of Zionism (see Leon Gettler’s An Unpromised Land, 1993).

Most Australian Jews are unconsciously cosmopolitan, recognising that there is no conflict between a Jewish ethnic or religious identity and Australian citizenship. But some go beyond this to an assertion that any attack on, or criticism of, Israel is an attack on all Jews. Perhaps they need to be reminded of the comment by the South African satirist, Pieter-Dirk Uys, that a patriot is someone who protects his country from its government. And perhaps they should read Rose’s book.

Comments powered by CComment