- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Rambling discourse

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The publisher’s puff to actor Michael Craig’s autobiography, a ‘fascinating, wittily wicked memoir of his life in film, theatre and television’, is unfortunate: not only is its conventional hyperbole on this occasion a cruel overstatement, but it misleadingly suggests a meaningful structuring of the events of Craig’s long career – in three media on two continents – that is nowhere apparent. Craig himself calls it more modestly a ‘rambling discourse’.

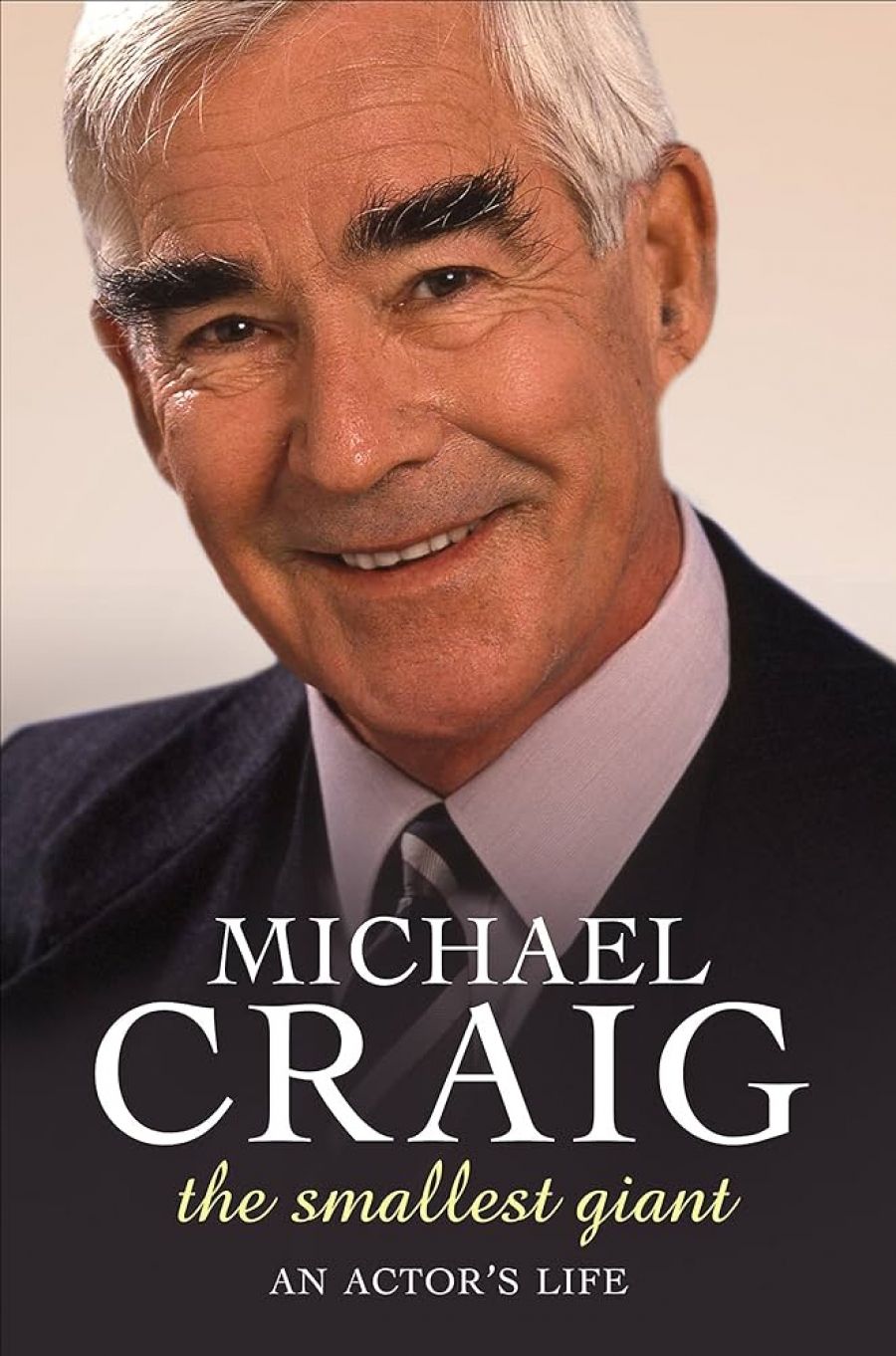

- Book 1 Title: The Smallest Giant

- Book 1 Subtitle: An actor's life

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95 pb, 268 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

A diligent editor would have urged Craig to discuss these experiences. No simple task, I imagine, for Craig’s mind is clearly not easily turned towards analysis or serious thought, either about the nature of the media in which he has worked, or the crafts of acting or writing. His philosophy of the acting business is explicitly stated in a dismissive paragraph about Method acting and the ‘buzzwords used’ by Lee Strasberg ‘to elevate a not-too-difficult craft to the status of an art’; and in the patronising tone of an anecdote about how a moment when colleagues covering for an actor who fell asleep in mid-scene passed unnoticed: ‘[S]hort of the set falling down or an actor dropping dead, audiences will accept pretty much anything.’ The scene in question occurred during a performance of Peter Hall’s 1964 RSC trilogy, The Wars of the Roses. Though he properly acknowledges this as an ‘almost legendary, landmark production’ in Shakespearean stage history, Craig scoffs at Hall’s ‘rehearsal process’, which ‘began with a four-day seminar on the life and times of fifteenth-century England’. Having discovered nothing to benefit his own character in the ‘politics, religion … cooking and education’, or ‘the state of the drains in Plantagenet England’, he recalls rehearsals as having been opportunities to ‘retire to the back to play Battleships’ with Nick Selby, an actor whose chief interests were ‘his beer and his pipe’. It was Selby who was guilty of falling asleep.

Craig’s own particular guilt relates to his repeated acts of infidelity towards his first wife, a luckless woman for whom, he confesses, marriage was a serious mistake. Coy, and not so coy, accounts of his sexual indiscretions abound. But mentions of the extramarital pregnancies for which he was responsible, how in Rome he ‘behaved a great deal worse than [he] should have’, his ‘little bit[s] of uncomplicated misbehaviour when the family wasn’t with [him]’, his ‘extravagant lechery and boozing’ are not only tiresome and tasteless, but not terribly amusing either. Nor are his anecdotes, apart from a splendid Gielgud faux pas, when ‘Johnny’ admitted having recommended Craig to producer Cedric Messina for a film role with the words, addressed innocently to Craig, ‘[I]t’s a terribly boring part, you must get Michael Craig’. The problem is that Craig is not a particularly gifted raconteur, either in terms of substance or style. As another reviewer has said, ‘[H]is contact with the famous – from Dirk Bogarde to Barbra Streisand to Judi Dench – has been so cursory that he has no really resonant stories.’ And he rarely lifts his style (pace the puff) above the flat and colourless, to reach the elegant wit of a David Niven or the sharp wisdom of an Alec Guinness – unless it be self-consciously to let fall the occasional vulgarism, or to press an Anglo-Saxon obscenity into service via reported speech. ‘Fuck’ and ‘fucking’ are particular favourites.

But Craig is not alone to blame for the book’s shortcomings. Far be it from me to imply that Allen & Unwin should have produced a work of high scholarship and deep research, but readers have a right to expect much, much better of such a reputable publishing house. Frankly, the quality of the copy-editing, proofreading, and indexing is appalling. To list the omitted words and typographical errors would be tedious. And although I fail to grasp the indexer’s rationale for the inclusion/exclusion of proper names, I guarantee there are at least a dozen in the text that do not, but should, appear in the index. And what is one to say about gross slovenliness such as ‘a Spanish comic actor whose name I don’t remember’; ‘Tartuffe was a new translation by some American professor’; ‘Peter O’Toole came to Sydney in some play’; ‘a sort of private eye show in which I think I played a baddie’ and ‘I have a feeling Paul [Nichols] was knighted before he died’? Finally, it is little short of offensive, in a theatre and film book, to find the following names misspelt one or more times: Jeffrey Dench, Paul Scofield, Jean Anouilh, Honor Blackman, Ronnie Fraser, Chris Haywood, Rhys McConnochie. On page 116, the last of these appears as Rees McConochy – three errors in two names! That’s how good this book is.

Comments powered by CComment