- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fluffy orange lumps

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

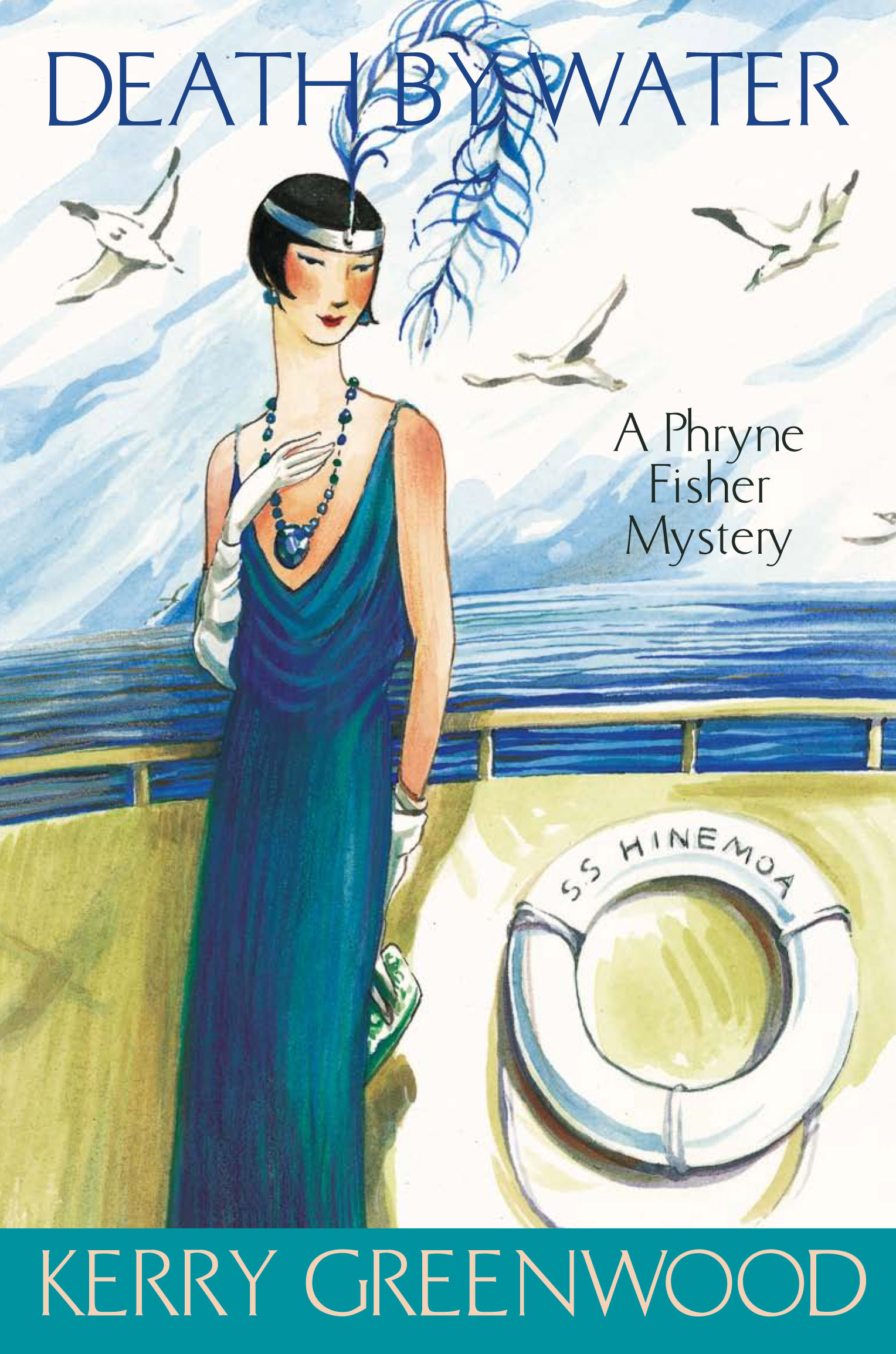

There is a trick to the trite title of Death by Water, the fifteenth volume in Kerry Greenwood’s series about the hedonistic 1920s private detective Phryne Fisher. Contrary to expectations, no murder occurs for more than two hundred pages. In the meantime, the nominal plot involves the hunt for a jewel thief aboard a cruise ship bound for New Zealand, but far more attention is devoted to meals, cocktails, cigarettes, clothes, dance music, maritime scenery, anthropological chit-chat and recreational sex. Literary quotes of approximate relevance head each chapter, while ratiocination occurs as an accompaniment to life’s more sensual pleasures: ‘Phryne ate a thoughtful croissant.’

- Book 1 Title: A Hand in the Bush

- Book 1 Biblio: Text, $23 pb, 240 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Death by Water

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $19.95 pb, 288 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

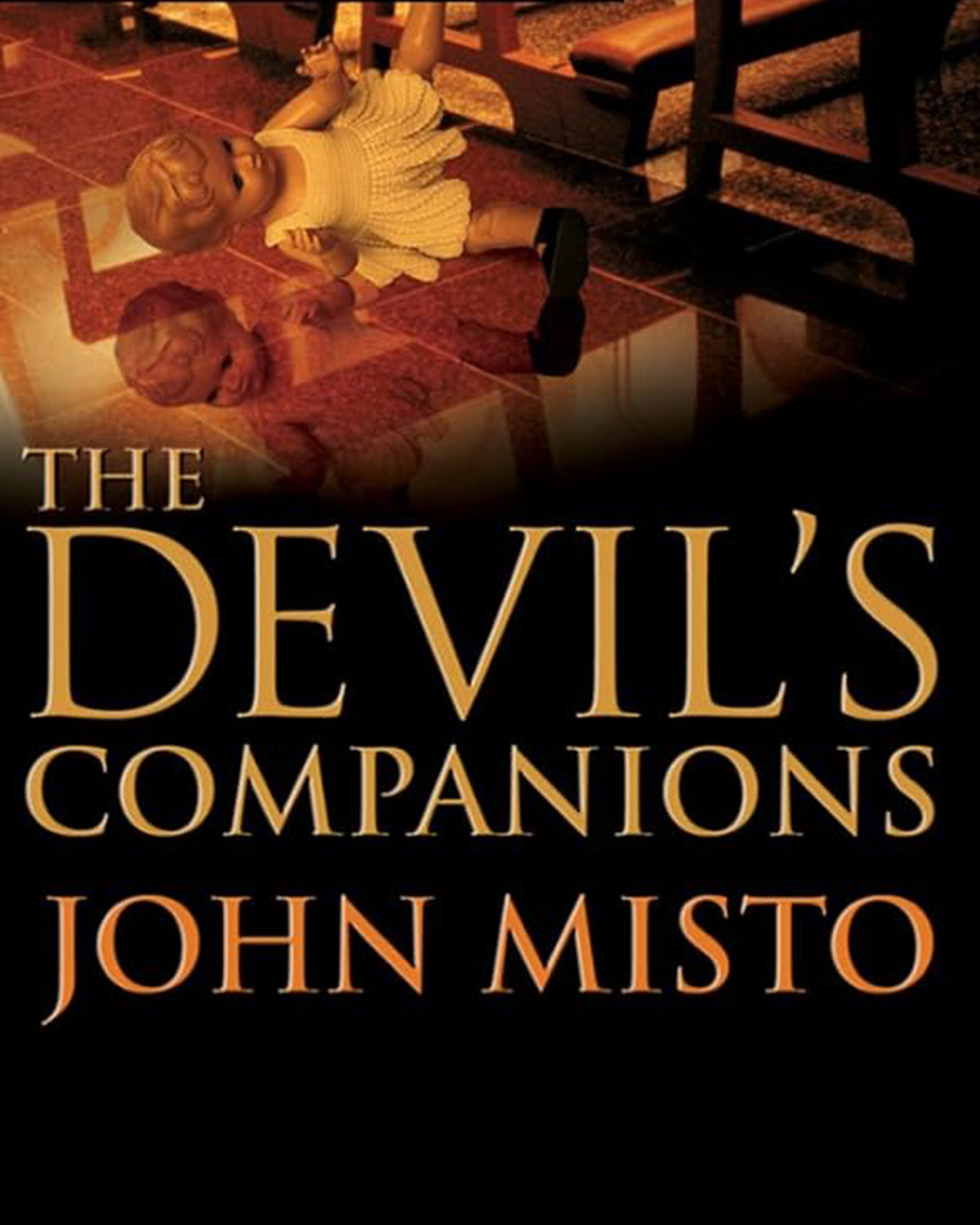

- Book 3 Title: The Devil's Companion

- Book 3 Biblio: Hodder, $32.95 pb, 265 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

For a while, it is possible to share the author’s enchantment with this daydream, but less easily seduced readers may feel that Death by Water displays all of its heroine’s tendency to self-indulgence without much of her advertised mental rigor. The trouble is that Phryne is the whole show: in this outing, which admittedly lacks many regular supporting cast members, she never finds an antagonist or sparring partner who can resist her wiles for more than a moment. As a series character, she’s as changeless and omniscient as Sherlock Holmes, but, unlike Holmes, she’s also a glamorous overdog lacking significant flaws or frustrations. She remains above and apart from the world she sails through, good-natured but finally insufferable. To be fair to Greenwood, the book is deliberately a trivial comedy of manners sealed off in space and time – though near the end, a breath from the chill wind of actual history comes close to bursting the bubble.

Jane Clifton’s A Hand in the Bush is set in the present, but adopts a comparable light-comic tone. Like Greenwood, Clifton aims for a blend of tough common sense and unapologetic frivolity; both writers retain an implicit feminism, at least to the extent of giving their heroines sexual agency and not letting ‘romantic’ subplots obscure strongly drawn friendships between women. Both also like their characters to live in handsome style, but, where Greenwood lets her imagination run away with her, many of the lifestyle and consumption patterns of Melbourne psychologist Decca Brand could plausibly be Clifton’s own. Correspondingly, her descriptive passages resort less to pastiche and show more interest in rendering sensuous experience, though the use of language is hit-and-miss: ‘The line between grey sky and grey ocean was indistinct and broken only by a fluffy orange lump.’

Elsewhere, the impression of a well-furnished fictional universe is created by a steady accumulation of factual detail: brand and street names are listed with a compulsion that smacks more of the copywriter than of the novelist. Heading out for dinner and a show, Decca’s date wonders if the pair should sample ‘a dose of grunge at the Esplanade Hotel in St Kilda’ or worship at the ‘temple of cool’ that is Fitzroy’s Night Cat. Such references are obviously meant to elicit nods of recognition from women of roughly the characters’ age and income level; I had the pleasure of recognising Melbourne landmarks, while eavesdropping on a social circle far from my own. But from any angle, the writing lacks tension: one longs for some sharper jokes that might jolt these comfortable forty-somethings out of their professional and personal routines and renew their zest for life.

The issue, again, is cosiness, an enticement for some readers and the kiss of death for others. Sexualised violence provides the mainspring of the plot in A Hand in the Bush, with three generations of women victimised by unlovely men. But the central intrigue is slow to take shape and inadequately resolved; Clifton keeps her villains on the side-lines and shows limited interest in their motives or possible attractions, settling finally for reaffirming the sisterhood. Nor does the threat posed by these figures cast any shadow on the ‘decent’ male characters, who are weakly portrayed at best.

The real theme on Clifton’s mind seems to be ageing, its losses and gains, and the survival of youthful ideals and fears into a more pragmatic present. A Hand in the Bush is at its strongest when juxtaposing the accustomed pleasures and defence mechanisms of middle age with what feel like authentic memories of less respectable times; best of all are the extracts from Decca’s teenage diary, written in groovy period slang and offering tantalising glimpses of a 1970s Australian lesbian (or ‘kamp’) subculture. Striking a less familiar note than most of Clifton’s journalistic observations, this material could almost have provided the basis for a book in itself, though perhaps not in the crime genre.

In comparison, John Misto’s The Devil’s Companions is a very different sort of crime novel – more sombre, more plot-driven, perhaps more ‘masculine’, though both that word and Misto’s approach conceal traps. Superficially a procedural cop thriller, the book is best described as an updated Gothic novel, complete with sinister crypts, secret organisations and a first chapter that begins on a dark and stormy night. The twist is that the persecuted innocent at the centre of the narrative is not the expected virginal young woman but a quasi-virginal young policeman, Greg Raine; though brave and personable enough to play the role of a hero, Greg is also a bit of a fool, comprehensively outsmarted by nearly everyone around him.

Misto is evidently drawn to male helplessness, having used a similar naïf as the protagonist of his absurdist ABC serial The Temptation of Harvey McHugh. But the quirkier side of his imagination barely emerges in this first novel, written in a bald, televisual style that suggests minimal faith in the attention span of the reader. Greg’s internal monologue provides a transparent record of his emotions; the supporting characters are types rendered with just enough unpredictability to anchor them in the mind (say, an Asian priest with blond-tipped hair and a Ralph Lauren T-shirt). As a thriller, the book is reasonably compelling, though beneath a veneer of realistic detail the plot feels over-simplified and improbably neat.

All three of these writers struggle to extract meaning from their personal concerns under the cover of genre, but Greg is a less flattering figure to identify with than Phryne or Decca, and his creator’s deeper intentions are more nebulous, perhaps allegorical. Certainly, the character takes on some of the attributes of a Christ-figure, slated for sacrifice by one or more powerful fathers – at the centre of the book are two families, Greg’s own and that of a politician whose daughter’s long-ago disappearance is being investigated. But after a series of twists that undercut our assumptions about who is really good or evil, it is hard to tell if Misto is a friend or foe of Catholic dogma, or if faith is simply another cover for a more primal psychological romance.

Comments powered by CComment