- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: From Teddy to Dubya

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The parameters of the twentieth century have, in the hands of historians, proved rather malleable. The need to contextualise the ‘End of History’, and a belief that eras are less arbitrarily and more accurately defined by events than by calendars, justified Eric Hobsbawm’s chosen bookends to his acclaimed Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914–1991 (1994). Harvard historian Stephen Graubard, in his magisterial exploration of the transformation of the American presidency during the twentieth century, extends the reach of the century into the twenty-first – a continuity justified by the redolence of the strategies pursued by George W. Bush to those of Ronald Reagan. For all the present incumbent’s protestations of paradigm shifts necessitating new approaches and responses, Graubard convincingly posits him among the twentieth-century presidents.

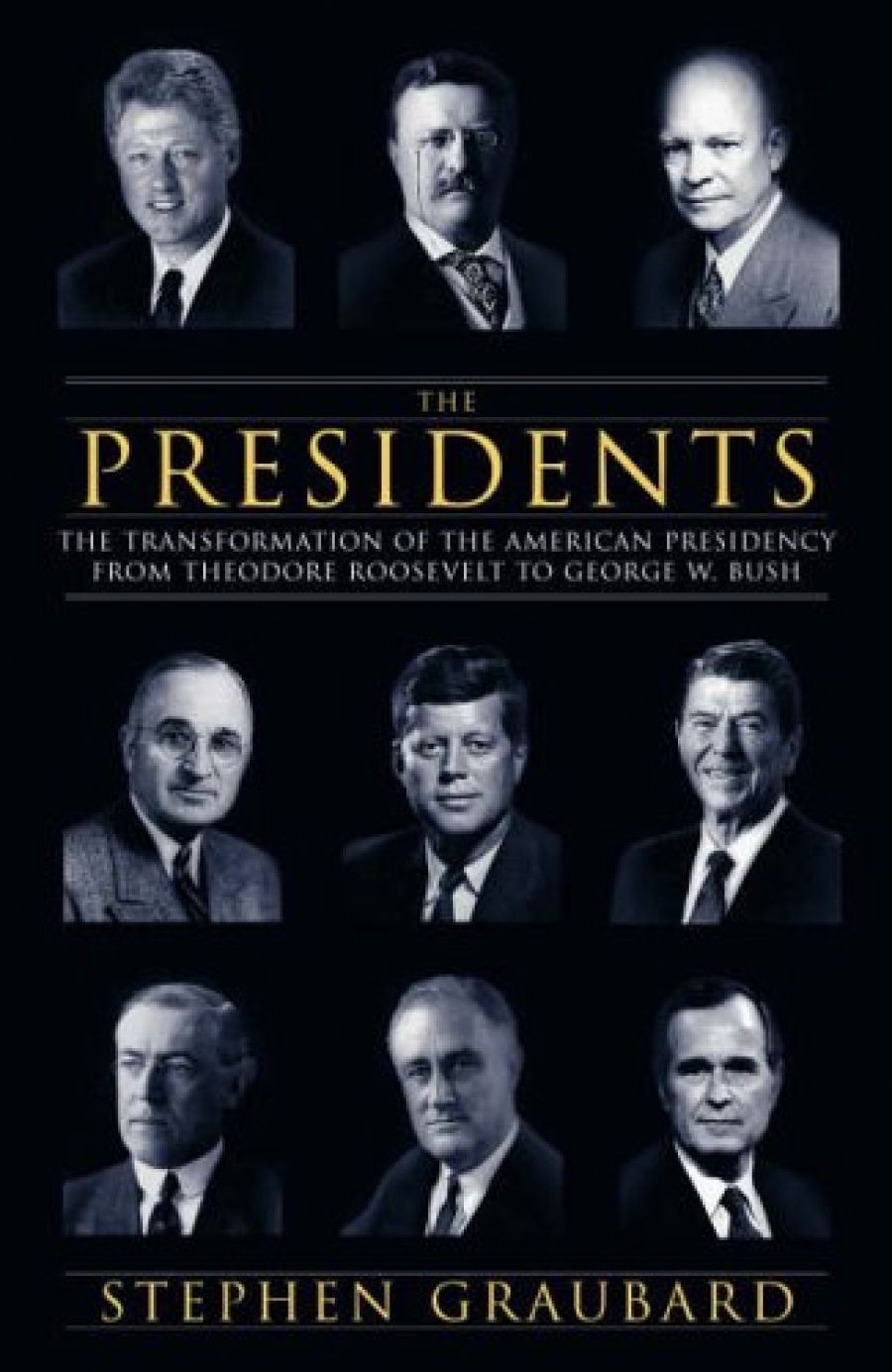

- Book 1 Title: The Presidents

- Book 1 Subtitle: The transformation of the presidency from Theodore Roosevelt to George W. Bush

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $69.95 hb, 928 pp, 0713996188

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The first of the twentieth-century’s metaphorical monarchs were not the first to question the primacy of Congress in the system of checks and balances created by the Founding Fathers. Andrew Jackson, for one, was acutely aware of the executive powers at his disposal. If Graubard’s ‘modern presidency’ was characterised primarily by imperial pretensions legitimated by executive power, then he would be remiss not to dissect the manner in which earlier presidents drew on their constitutional prerogatives. His expertly justified starting point is not Jackson, however, but the early nineteenth-century French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville, who prophesied that the presidency would emerge as the most powerful branch of government as the country’s engagement with the world increased. Graubard’s survey of the presidency’s evolving character rightly lauds Tocqueville’s prescience, while lamenting many of its implications.

Were Graubard charged with carving his own Mount Rushmore, the visages to emerge would be those of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman and Woodrow Wilson. Teddy, who ‘vindicated all who believed that learning and passion mattered’, would hold his place. While unsparing in lambasting his various foibles, Graubard affords Wilson a place in the pantheon of presidential giants. For all his rigid and ultimately counterproductive idealism, there inhered in the office vacated by Wilson an ascendancy and grandeur that would, following an interregnum, reach its apotheosis during the terms of FDR and Truman.

While Graubard’s veneration of FDR (‘the century’s incontestably greatest president’) might be uncontroversial, he does not skim over his wily pragmatism. Graubard’s labelling of the presidents who followed FDR as ‘prevaricators’ and ‘dissemblers’ borders on the repetitious, but his point is well made. Depicting the debasement of the office, Graubard heaps opprobrium on those who he feels were not up to the task. His standards are exacting, his tone disdainful. John F. Kennedy is depicted as the beneficiary of an unwarranted posthumous deification; Eisenhower is derided as ‘a five-star general out of his depth in the White House’. Perhaps his most trenchant criticism is reserved for the hapless Jimmy Carter (‘honest but inept’), though Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush are similarly skewered. His assessments of Lyndon Johnson (‘an incomparable reform president’) and Reagan (‘an accomplished, self-invented hero’ who did much to restore the institution to its previous grandeur) are more ambivalent. Reagan’s accomplishments, however, are in Graubard’s eyes tempered by a legacy bemoaned in his coruscating denunciation of the current presidency.

For all the assembled historical and biographical information, there are some startling omissions – none as inexplicable as the eliding of Truman’s decision to deploy the atomic bomb. Also on Truman, Graubard neglects to discuss his failure to seek the consent of Congress prior to intervening in the Korean War. Nowhere is it suggested that this prefigured a presidential prerogative that would manifest tragically in the country’s descent into its Vietnam nightmare. Korea scuppered Truman’s hopes for the Fair Deal just as surely as Vietnam was the ruin of Johnson’s Great Society.

For Graubard, perhaps the most demoralising concomitant of the degeneration of the presidency has been the succumbing of the American people to what Tocqueville called the ‘soft and idle terror that wears hearts down and enervates them’. In an age ‘wedded to hyperbole’, and with the American public in the grip of an importuned terror, Graubard concludes this ambitious and important book by offering a Tocquevillian diagnosis of an American mind ‘too easily excited’ and ‘too easily satisfied’.

Comments powered by CComment