- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The ghosts of Lodz

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Henry Pollack, the founder of Mirvac, one of Australia’s largest and most successful property development companies, started life in Lodz, a booming Polish textile town. Born in 1932, he belonged to a well-to-do family and became a bookish boy. He writes about his youth with vivid openness, describing not only events but his feelings, thoughts and youthful ideals. With this memoir, written towards the end of his life, Pollack comes close to being the writer he dreamt of becoming as a boy. Memories of his childhood have a fidelity and clarity that may well be the result of a life lopped and restarted at the age of sixteen; those early years are preserved as if in a time capsule.

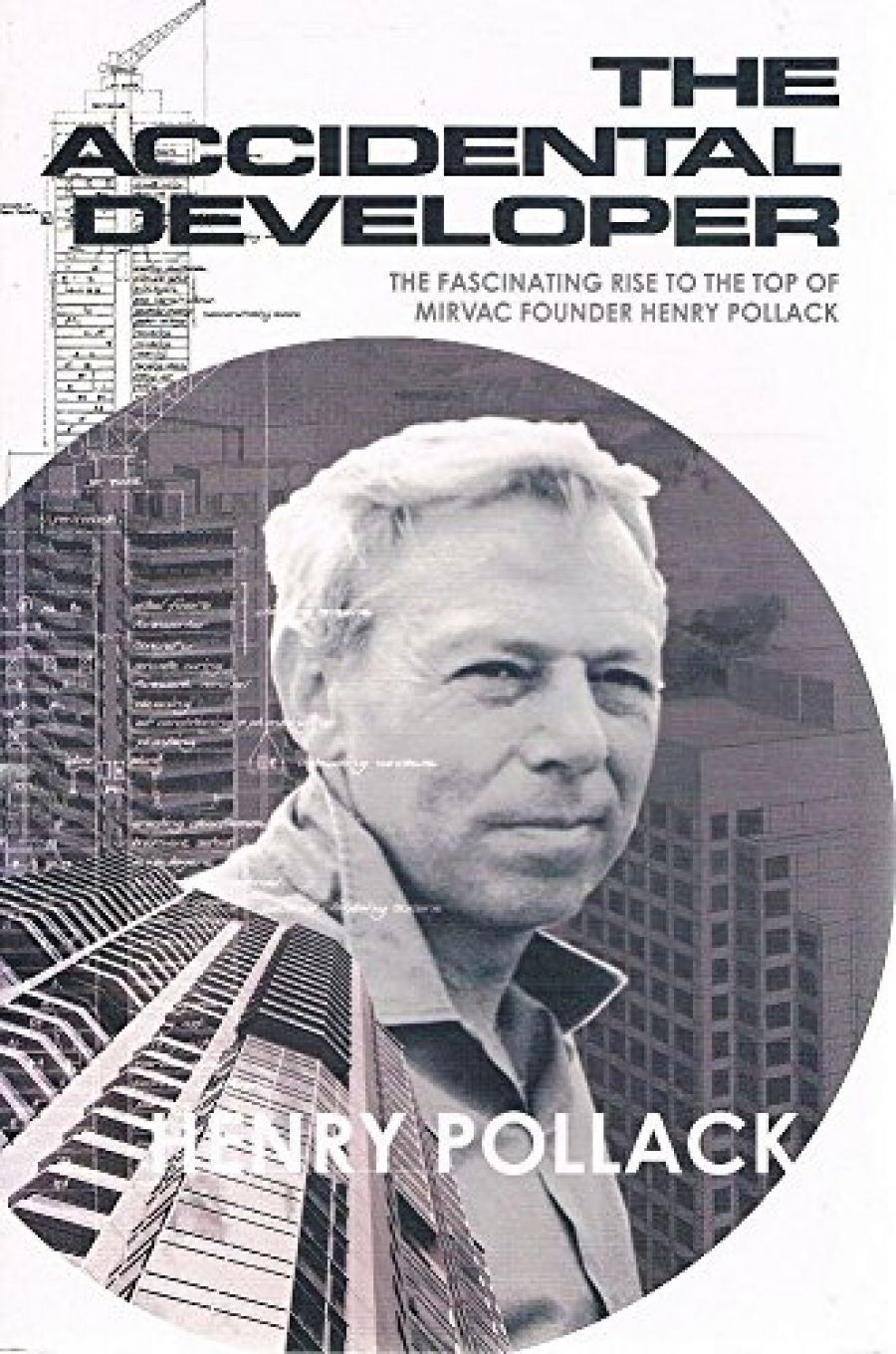

- Book 1 Title: The Accidental Developer

- Book 1 Subtitle: The fascinating rise to the top of Mirvac founder Henry Pollack

- Book 1 Biblio: ABC Books, $32.95 pb, 345 pp, 0733315895

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Henry cycles to Vilnius, in Lithuania. Two months later, he perilously rides back to Nazified Lodz, in search of his parents, who by then had escaped to the Warsaw Ghetto. On the way back to Vilnius, he is stopped by two uniformed Nazis, told to get in, with his bike, and to show them the way. When he asks a young Polish peasant woman for directions on their behalf, she refuses and as they drive off they take potshots at her. A male peasant runs to save her:

The driver aimed the car straight at him; the Mercedes star homed in like a gun sight on his chest. He swung to the left and ran on the side of the road and for a few moments dropped out of view, but the star soon found him and its spokes homed in again like crosshairs on his breast. The engine revved up and the car went faster. When the peasant realised the driver’s intention it was too late. I saw his face, mouth half-open, through the star, heard the thud and felt the impact. The body rose and fell on the bonnet and rolled off. As we drove on the lieutenant said, ‘Bullseye. When a bull charges, you take him by the horns.’ I didn’t want to test the Germans’ patience. It was safer not to see or hear anything. I did not look around to see what happened to the peasant.

We don’t see much death and destruction, but we are keenly aware of the world turning to hell behind us. As Henry flees all the way across Russia to Japan, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Surabaya, we are brought face to face with this unimaginable war that roars east across the world.

In December 1941, after two years of extreme experience, Henry, still a teenager, reaches the safety of Sydney, where he builds a big life in the shadow of profound loss. As the full extent of the carnage in Europe becomes known, he learns that everyone in his past has ceased to exist. Not a single member of his family and not one of his school-friends survived.

He is driven by his mother’s exhortations to be a mensch, and at all costs to avoid becoming a Luftmensch, a footloose businessman who lives by his wits, literally someone who lives on air. This may be an unlikely ethos for a man who ends up building a major public company, but it’s one that he struggles with throughout his life. He trains to be a watchmaker, a practical and portable profession; he acts in Jewish plays; he matriculates, studies for an arts degree at Sydney University and becomes enthralled by the philosopher John Anderson; and he marries a gifted musician.

Pollack eventually succumbs to business and turns a small Leichhardt shop, intended for watchmaking, into Belle Star, the first of a small chain of women’s fashion stores. The years pass, but his mother’s admonition persists, and in his late thirties he decides to study architecture: a profession, not a business. But as an architect, he soon finds that jobs are hard to get, so he begins to develop his own projects, again becoming a Luftmensch. Mirvac is born, and the rest is history. Pollack died last year, but the company he began is still in the top fifty Australian companies for capitalisation and share-market value. Although he achieves success, Pollack’s painful memories never leave him. Throughout his life, he dreams of his murdered schoolfriends, who drive him to extreme guilt for having survived and who seem to demand to be allowed to live through him.

Henry Pollack’s memoir reveals a decent man with a rational, highly ordered mind, which he applied to his work and which is evident in his writing. His pragmatic nature destined this book to fall short of literature, but it does have its moments. In 1989 he visits his old classroom in Lodz:

I called out by the first and second names the eleven Jewish boys in the year, one by one in alphabetical order, and waited for a response. A noise of distant traffic came through the windows. When my turn came I answered loudly, ‘Here’ … Then I took out the text of a funeral service I brought from Sydney and read out, in a stiff and angular Hebrew of one who is a stranger to the language, the sad and solemn sounding words Yiskadal vy Yiskadash of the prayer for the dead.

This moment – understated and poignant – characterises the strength of this compelling memoir.

Comments powered by CComment