- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hands up!

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Hands up if you subscribe to an Australian journal. Keep them up if you subscribe to more than one. More than two? If you read them? Cover to cover? Half? More than two articles an issue? Hands up if you look forward to them. Maybe it’s just me, but there’s something that makes me terribly tired when faced with the prospect of Australia’s literary and political journals. I stand in front of the (small) shelf made available for them in my local bookshop and try to muster up the enthusiasm I might feel when faced with a shelf of new books; try to feel excited at the prospect of reading them. I have a couple of subscriptions, and when they arrive, I make a point of tearing the envelope open immediately to have a look. And yet I still have to push past a barrier of resistance to sit and actually read them.

- Book 1 Title: Griffith Review 8

- Book 1 Subtitle: People like us

- Book 1 Biblio: ABC Books, $16.95 pb, 230 pp, 14482924

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

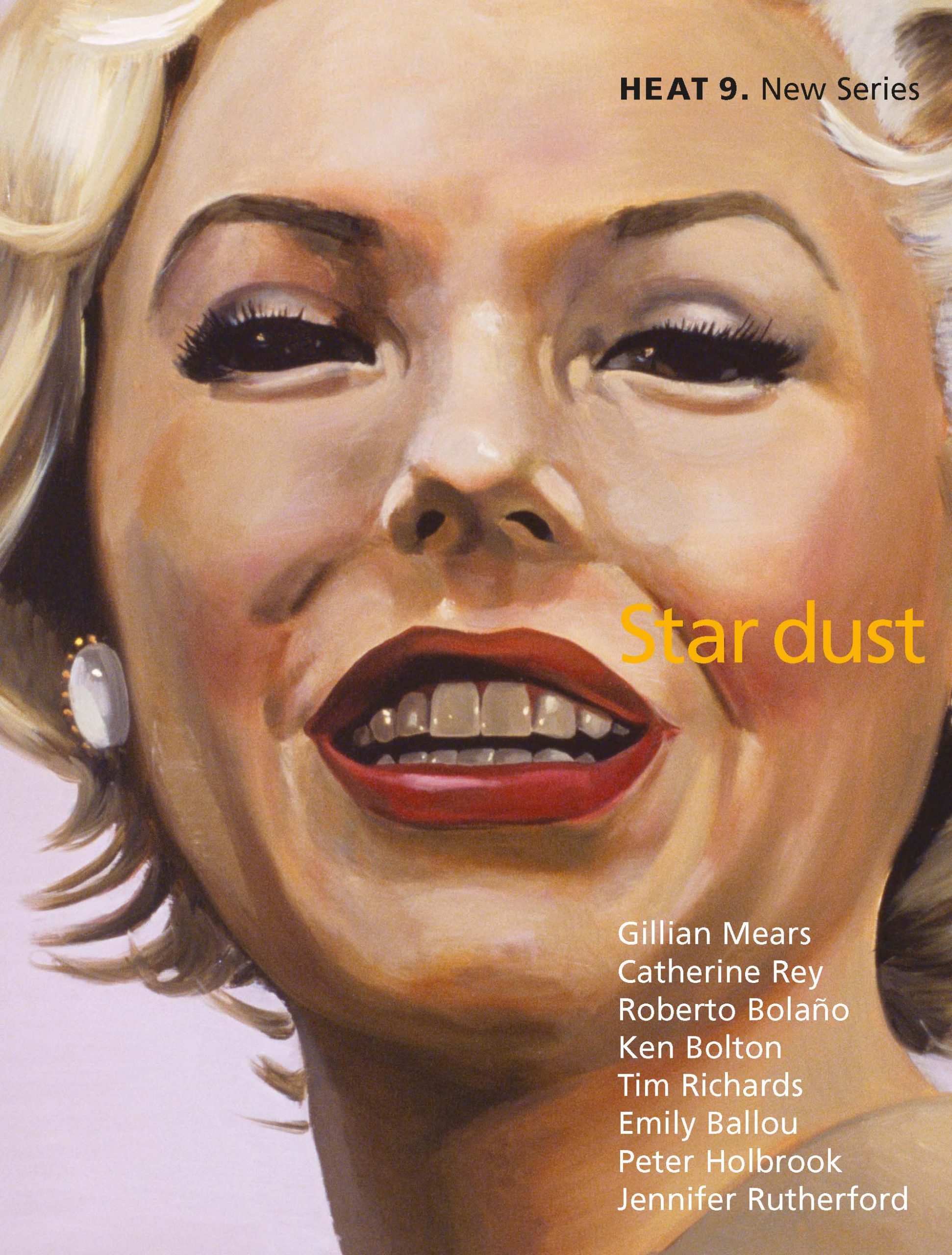

- Book 2 Title: Heat 9

- Book 2 Subtitle: Star dust

- Book 2 Biblio: Giramondo, $16.50 pb, 256 pp, 13261460

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Island No. 100

- Book 3 Biblio: $20 pb, 224 pp, 10353127

Attempts by quarterly journals to shape their issues along thematic lines yield mixed results. Sometimes it smacks of contrivance, but when it works it can provide much-needed coherence. The latest Heat gives a nod in that direction, but it’s quite clear early on that nobody is clear quite what is meant by ‘Star Dust’ as a title. This lends the whole enterprise an air of inscrutability and distance that seems oddly appropriate. At least we are spared the tedium of an editorial contorting itself to bind the disparate pieces together. Ivor Indyk allows the pieces to stand on their own, and this is a good decision, because he’s brought together an unwieldy mixture.

Too often the non-fiction contributions fall back on jargon and dense obscurity. Peter Holbrook is very good on the painting of Anne Wallace, combining literary and visual art criticism to impressive effect. Evelyn Juers and John Mateer are both characteristically strong on actress Carla Mann and South African artist Kendell Geers, respectively. But I got a little lost in Jennifer Rutherford’s discussion of re-spatialisation of sexual relations in ‘The I, the Eye and the Orifice’. Brendan Ryan’s rumination on walking (like a cow and otherwise) has some lovely writing in it, but overwhelmingly left me asking: ‘what’s all that about?’ The uneasy variety of contributions to ‘Star Dust’ epitomises the strengths and weaknesses of this journal. Despite my churlish preconceptions, there’s never any sense of Heat taking the easy or obvious option with its contents. Ranging from the surprising to the difficult, they are bound together by an energetic and sceptical attitude to language and a clear desire to challenge rather than reassure. When it fails, it’s unreadable (but not for lack of vision). When it succeeds, it more than justifies its existence. The strengths here are in the fiction and in the poetry: both are uniformly impressive in this issue. Read Heat for both, you’ll find much that is unexpected and invigorating.

Island, on the other hand, is guilty of not challenging expectation or convention enough. It deserves congratulations for surviving 100 issues and for continuing to provide a forum, particularly for Tasmanian writers. Sadly, this landmark issue does not have a great deal to recommend it. The journal’s relationship with the Tasmania Pacific Region book prizes is terrific, and it makes sense for them to run some material in conjunction with the awards, but the policy of running extracts from all twelve shortlisted books in a single, somewhat unruly block feels like a mistake. Almost fifty pages of grabs from any range of works might feel fragmented and perfunctory at the best of times, but, given the awards are biannual, this selection also serves to give the journal a dated feel. It’s possible that some of Island’s readers might have missed Michelle de Kretser’s The Hamilton Case or Alex Miller’s Journey to the Stone Country when they first came out, but three-page grabs from each book with no critical engagement won’t do much to change that.

Brevity is an asset in a collection such as this, but the layout and the shortness of most contributions makes it feel choppy and ill-considered. It’s hard not to feel that the contribution from Richard Flanagan – a discarded screenplay for a short film – is there because he’s Richard Flanagan rather than because the script is in any way meritorious. It’s fine, but unnecessary. Same with the contribution from Henry Reynolds; a good enough piece, but it reads like the discarded scraps from a longer, more meaningful piece. I wish the editors well and trust that regular non-anniversary issues have more scope to allow their writers to let loose. The number of contributions from previous editors seems like a nice way to mark the 100th issue, but nothing here really surprised, challenged or – worst of all – particularly entertained for more than a sentence or so at a time. None of it felt sufficiently new or vital to overcome my early doubts.

Initially, the latest Griffith Review, ‘People Like Us’, seems to fall into the same trap. Margaret Simons is a fine writer, and her recent pieces on insider–outsider politics in Australia, in the divide between the suburban and urban experiences, have been a vibrant and well-reasoned contribution to cultural debate – if occasionally a little self-justifying. But coming to her piece in Griffith Review, I felt as though I had read her thoughts on the subject several times already. Cue the fatigue. Much the same could be said of John Marsden on comedy, or Simon Caterson on satire. I want to be clear – these are all well-written pieces on worthwhile topics by talented writers; but there’s a finite number of times I feel inclined to read navel-gazing tracts on why ‘Kath & Kim’ is so successful (for the curious, the number is about 0.34). Both of these pieces, when you read them, offer their fair share of insights and amusements. The problem, yet again, is one of expectation. Same old, same old is not necessarily a bad thing, but when there’s too much to read anyway …

Luckily, for once the thematic approach works, and works in spades. Cumulatively, as you continue reading the latest issue of Griffith Review, the ideas come together to form a complex and energetic picture of what might be meant by the phrase ‘People Like Us’. To put it in somewhat hackneyed terms, the whole becomes more than the sum of its parts. By offsetting the familiar with the surprising and unexpected, each piece feeds into those surrounding it. The result is deeply rewarding. Serious and engaging, this is a journal that deserves to be read cover to cover. Even the missteps add to the issue.

The dry asides in Daniel Flitton’s review of the relationship between country and city life bring a well-considered topic alive: ‘the PM’s Akubra is the style described as the “Pastoralist”, which the company declares “will have great appeal for the grazier and stock and station agent and [is] most suited for women’s casual wear”.’ Similarly, David Dale clearly enjoyed himself putting together his take on the 2005 census. His playful tone and ironic juxtapositions make it terrific fun to read: ‘The bureau tells us that women are more likely than men to be old, living alone, at the movies, using a library, seeing a doctor, in a botanic garden, sexually assaulted, walking for exercise, suffering arthritis and asthma, and using contraception.’

Tamara Dean’s photo-essay on Brad Mooney is evocative and dynamic. Regular Griffith contributor Melissa Lucashenko’s essay on Palm Island should be compulsory reading: clear-eyed, angry and articulate, it’s an exceptional piece. Madeleine Byrne, writing on the staff at Woomera, manages (improbably enough) to be both impassioned and dispassionate. And on a vastly different but complementary note, David Sornig captures beautifully the agony of adolescent friendship. It’s the things these writers tell us about subjects we already feel we’ve heard enough about that make this such an essential – and enjoyable – read. I can’t think of a better expression of contemporary Australian critical and cultural identity. I might even subscribe.

Comments powered by CComment