- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

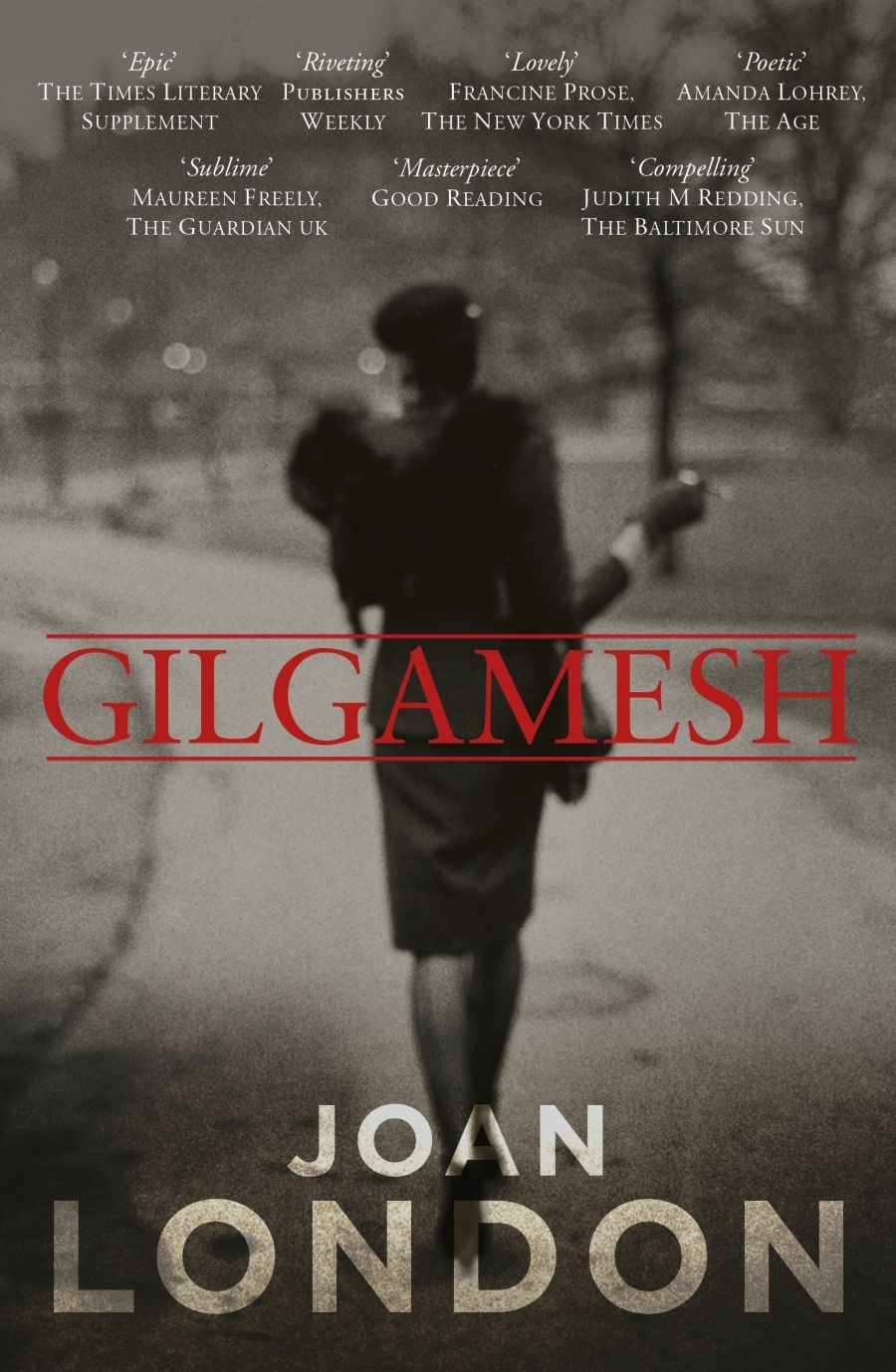

- Custom Article Title: Stephanie Trigg reviews 'Gilgamesh' by Joan London

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Joan London’s new novel, Gilgamesh, is the story of several generations of travellers, moving between Australia, London, and Europe, as far east as Armenia. As such, it is part of a long and venerable tradition in Australian fiction: a tradition of quest narratives organised around topographical and cultural difference ...

- Book 1 Title: Gilgamesh

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $28 pb, 255 pp, 0330362755

When Leopold and Aram arrive to find the girls living in such unexpected poverty, sharing one pair of shoes between them, Leopold makes them laugh by trying to train his own ‘fishbelly white’ feet to go without shoes; and ‘It was a long time before Edith understood the gallantry of his performance’. Throughout, London underplays the hand of cultural comparison, displacing and deferring its effects in this way, rather than foregrounding them directly. She even plays with the idea of structural opposites. The cab driver who brings Leopold and Aram to Nunderup appears in an intriguing cameo of obsession that deftly also helps us visualise the differences between the strangers:

One was wiry, dark as a Gyppo, the other fat, spoke like a Pom ... All things come in twos, thought Bickford. Fat and thin, old and young, dark and fair. Good years and bad years, hot summers and cold winters. Crook and well, happy and blue. Peace and war. Married and single. His whole life could be fitted into it … Sometimes it clicked in his head and wouldn’t stop.

Once the visitors leave, and after the younger girl, Edith, has borne Aram’s child, the major quest narrative is set in place, as Edith decides to travel to Armenia to find him. After a nightmare journey, she and baby Jim take a bath together in the London home of her Russian aunt Irina: ‘After their bath he was soft and fragrant like an open flower ... Their clothes looked like rags in a pile on the floor, stiff with sea salt.’

Gilgamesh is written in a wonderfully economical prose, alternatively bristling and resonating with suggestiveness. For example, ‘She felt dizzy, as if she were leaving a coastline’. But in which direction – inland, or towards open sea? As with many of London’s images, this one follows its initial impact with a little after-charge of uncertainty. And, when Edith arrives in Georgia in 1939, without a visa, and confronts the Customs officials: ‘The kangaroo and emu on her passport looked as innocent as a nursery frieze.’ This is typical of the entirely unsentimental and understated nature of the writing in this novel, especially around the central character. Edith makes her journeys, and her life is transformed, but change registers slowly, and often retrospectively, pages after the telling; and the novel is no less moving for this restraint.

The narrative device of the ur-text – in this case, the ancient Mesopotamian epic of the hero Gilgamesh, his mourning for his beloved friend Enkidu, and his eventual homecoming – is a wonderful aid to such restraint. The retelling of the old story, even in fragments of counterpoint, carries much of the passion and the depth that Edith’s own story does not articulate directly. In Yerevan, Edith is illiterate, without a calendar or even newspapers to give her the date, and resorts, at first, to ‘marking off days by pencil strokes on the back of an old book, like a prisoner. She’d been terrified of being lost in time as well as space.’ However, for the reader, she is never lost, as the story of Gilgamesh – the ‘old book’ Leopold carries with him – serves as a guarantee both of closure and of historical repetition. The story of Gilgamesh is also a story of homosocial love; and once more London allows this narrative to do its work by indirection, just sketching in a possible trajectory for Jim’s own journey at the end of the novel.

Because the novel’s structural strengths lie in the way it compounds its narratives, and the way it sets up retrospective echoes and charges, the opening sections may not initially enthral. Think of them as the first phrase in a Bach fugue, and you will get some idea of the riches to come.

Comments powered by CComment